From Sight and Sound (Spring 1984) -– designed as a sort of spinoff/update of my recently published book Film: The Front Line 1983. -– J.R.

Item: In assorted outdoor locations all over the US, from a Santa Monica pier to a park in lower Manhattan’s Soho, Louis Hock has been showing a silent, triple-screen film of his own devising called Southern California. The film’s imagery is of the colorful, mythical sort that its title suggests: placid neighborhoods flanked by palms; a San Clemente flower farm; fruit and vegetables in a La Jolla supermarket; downtown Los Angeles glimpsed from the rotating Angel’s Flight Bar or from the top of the Hyatt-Regency. Southern California is actually one strip of film run consecutively through three adjacent 16mm projectors which are aimed at the same wall.

There’s a gap of 22 1/2 seconds between the time that the first and second panels in the triptych appear, and again between the reappearance of the same images on the second and third panels. Every image, consequently, appears twice in each 45-second cycle.

Rather than promote his movie in any ordinary way, Hock usually finds a public site (like the University of California’s San Diego campus, or the street level of the South Ferry terminal in New York, where Staten Island commuters pass), sets up his gear, waits until nightfall, starts to show his 70-minute film on a continuous loop and waits to see what happens.

Responses differ widely, and Hock appears to savor them all. Some people walk hurriedly past; others stop. But in general people who have little else in common — most of whom had no intention of watching a movie in the first place, on their way to something else — find themselves entranced. The sheer beauty of Hock’s landscapes rippling across the three screens, which sometimes trick the eye and mind by resembling one continuous widescreen landscape rather than three successive moments in the filming of a more narrow one, are occasionally undercut by subtitles. These describe what is being seen in the phrases of advertising jargon (‘window to the world’, ‘renowned public amusements and murals’) and recur and link up together along with the images.

Some passers-by assume that the film is some kind of literal advertisement. Others react more positively: Hock is fond of recalling a punk rock band called the Armaghetto Ensemble, who turned up in the parking lot of the Santa Monica pier on a flatbed truck and furnished free musical accompaniment. Before a rare indoor screening at Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archives, which played to a cheering capacity crowd, Hock encouraged the audience to get up and move about, laugh and talk if they wanted to; and they did.

Does such a screening set-up have political implications? Yes and no, according to Hock. Yes, in the sense that this is a ‘truly public film rather than a commodity’, set in the mundane public context of ‘the billboard, the bus bench and the parked car.’ No, in the sense that Hock regards it as, ‘Simply the logical extension of my work and the best way to show it. I want an image bigger than those existing in available theatres. I want the audience to see the film from various angles and while moving. I want a large, heterogeneous audience to see my stuff, rather than the handful of familiar faces.’

Question: Is Southern California an avant-garde film, a public amusement, or a mural that moves? To what degree is the genre defined by the audience it attracts?

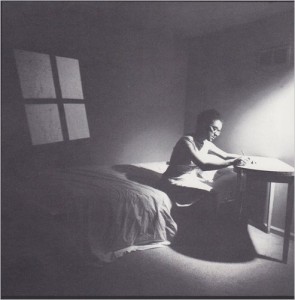

Item: Sara Driver’s compelling You Are Not I, a stark 5O- minute adaptation of a short story by Paul Bowles narrated by a schizophrenic, was shot in black and white by a New York University graduate in her twenties. Stunningly acted (by Suzanne Fletcher, as the mad narrator and protagonist, who escapes from a mental hospital during the confusion after a nearby multiple car crash, and by Melody Schneider, as the uptight ‘normal’ sister who unexpectedly finds that she has to cope with her), the film is also shot and paced with a brutal rigor that suggests the style of a master like Carl Dreyer; the eerie music score (by Phil Kline) and subtle sound effects are no less striking. The overall effect is of a wilful imagination bringing a deranged vision to life, piece by piece, confident in its power to overwhelm the world that we ordinarily regard as the real one. A conundrum about the boundaries of sanity and female identity, You Are Not I has earned a reputation at European festivals, and had a successful run last year at Manhattan’s Public Theater (on a bilI with the cult melodrama The Honeymoon Killers).

To date, however, hardly a single publication in the United States has bothered to review it.

Question: Is You Are Not I an avant-garde film, a European art film made by an American, or an experimental narrative of indeterminate length that eludes such categories?

Item: Candace Reckinger’s Occupied Territory, a half-hour science fiction short in colour, about an international all-female terrorist group, has also fared well in Europe and not been much seen in the U.S.A. Like Hock but unlike Driver, Candace Reckinger has had a good deal of previous involvement with avant-garde film-making. She says that she wanted to make a film which was disturbing, and usually can’t get it shown for precisely that reason. Too slick and well-crafted to make it in avant-garde venues, Occupied Territory is also too short and too intellectually challenging to wind up in the mainstream.

Mutatis mutandis, the same general problem holds for some of the most talented women film-makers currently working. Their originality banishes their work from conventional categories, even within the avant-garde. Leslie Thornton’s beautiful and beguiling Adynata, an extraordinary non-narrative meditation on the fantasies spawned in the West about the Orient, can’t deal with the fanciful racism that resides in our imaginations without being rejected by at least two trendy avant-garde showcases in New York for being racist.

Ulrike Ottinger’s wild and hilarious German feature Ticket of No Return has too much high-fashion,storyline and Tati-style visual comedy to qualify as underground, too much eccentric inventiveness to find its way into the local Bijou. Reassemblage. a short about Senegal by Trinh T. Minh-ha, a Vietnamese writer and musician based in Berkeley, has an analytical bite and jagged editing thrust worthy of Godard, both pressed to examine the way we look at alien cultures, but not the sort of calling cards likely to persuade American Godard fans to see it.

Question: (a) Are Adynata, Occupied Territory, Reassemblage and Ticket of No Return avant-garde films? (b) As far as official avant- garde channels are concerned, do they exist?

Item: Movies as diverse as The 7 1/2% Solution (a Hollywood feature), Bad Timing (an Anglo-American art-house feature), and Raw Nerves: A Lacanian Thriller(a Mexican-American avant-garde short) all have the same theme in common: the crossbreeding of psychoanalysis and the detective story. But where can one go to find these three films discussed together? Fans of the first and/or second are unlikely to have heard of the third, which is arguably the best and most original in the bunch. Manuel De Landa’s Raw Nerves might also be regarded as the most ambitious, in so far as it constitutes a reasoned critique of Freud and film noir alike. De Landa plants his detective narrator in a public lavatory, where he spies a mysterious coded message on a wall — an allegorical depiction of a child’s discovery of language, which implies that even a baby enters a social field as soon as language is encountered. Pitched in a zany manner which seems to reside somewhere between Mexican camp and Frank Zappa, Raw Nerves uses shrieking Day-Glo colours and violent optical transition devices to keep the spectator hurtling through the Kiss Me. Deadly style mystery plot, and concludes with a surprise ending which takes apart the detective story genre itself.Unlike most of the films cited above, Raw Nerves is usually packaged and shown as an avant-garde product, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s allowed to exist in the same world with other films which explore the same theme, or that certain avant-garde programmers haven’t derided it for not being more difficult to watch. Indeed, while some avant-gardists have objected to its strong narrative base, its avant-garde credentials tend to segregate it from the more popular movies that De Landa would like to make. (Having worked in computer animation used in TV commercials and station logos, he is not exactly a stranger to the mainstream.)

***

Question: How much does the term ‘avant-garde’ serve to direct us towards certain films, and how much does it serve to direct us away from them? ‘The bad thing about the term,’ says De Landa, ‘is the bad thing about the notion of a vanguard in general -– whether you’re talking about the Communist party or about art films. It’s a nineteenth centurymilitary conception. It presupposes the Leninist notion that they are the representatives of the lower’ exploited classes — or, in this case, they’re representatives of the visionaries, of a different vision. And as soon as the avant-garde becomes their representatives’ it’s ridiculous, because it has never been like that. It has always fed on the most bizarre and contradictory tendencies going on at the same time, and that’s what keeps it alive. The term lends itself easily to the use of people who want to construct a unified project –- the vanguard project, the vision that everybody should have if they want to make films that are “politically correct”, whatever sense you can give that term when you’re talking about experimental film. On the other hand, it identifies a particular consumption set-up which in the U.S.A is the college circuit, film club and film magazine –- something which has its roots in history. That’s all right; it’s nicer to have a term to refer to.’

De Landa admits that the institution of avant-garde films is useful to certain film-makers like himself, who want their work seen within a knowledgeable contest, and less helpful for film-makers, critics and programmers who wish to address themselves to a broader spectrum. But in order to understand the roots of the problem more clearly, more than just the avant-garde has to be looked at; the mainstream has also to be considered. For one thing, mainstream critics are much more conservative in their tastes nowadays than they were twenty years or so ago, when fashionable art-house far tended to run more in the direction of challenging narrative conventions. (Later on, these challenges would harden into the tropes of lesser directors, and fresh challenges were avoided.) Film-makers such as Antonioni, Godard and Resnais –- who were then feared, debated and respected in rather the same fashion that Woody Allen, Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma are heeded today — might have been regarded with suspicion or outright hostility by several prominent critics during the 1960s. But at least they commanded more overall attention — to the degree that they often made many of the more entrenched American independent film-makers envious and resentful.

Such major films as Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad and Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, despite their bold formal departures, were rigorously excluded from the avant-garde canons of taste which nurtured talents like Stan Brakhage and Kenneth Anger, with the result that innovative film-making began to develop two nearly autonomous traditions, each of which was pridefully ignorant and dismissive of the other. At best, this functions as a kind of friendly schizophrenia which often ensures, in ghetto fashion, that critic A deals with big-budget experiments while critic B deals with low- budget ones-and that A and B hardly speak to one another, except on special occasions. Somehow the unaffiliated and in- between spectator, who might be delighted by De Landa as well as Fellini, or by Louis Hock as well as Kubrick, gets boxed out of existence, leading to a mistrust of the implied world views of critics A and B alike.

In all fairness to the avant-garde tradition, its tolerance for a variety of viewpoints has certainly grown in the last few years: films with storylines are far more plentiful in avant-garde showcases than they used to be, for instance. But the tolerance of mainstream critics for difficult films has correspondingly shrunk — leading to odd disparities for many of the rest of us. If the latest films of the English film theorists Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey garner more attention in the U.S. today — more screenings and commentaries, that is — than the latest films of Robert Bresson or Jacques Tati, this certainly isn’t because Wollen and Mulvey are more interesting and important as film-makers. It’s merely because avant-garde programmers, distributors and commentators are equipped to deal with Mulvey and Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx (1977) and Crystal-Gazing (1982), and their mainstream equivalents are unable to cope with Bresson’s Le Diable, Probablement (1977) and L’Argent (1983) or Tati’s Parade(1973) — all of which have yet to reach the United States. Meanwhile, Wollen and Mulvey encounter few of the difficulties in getting their recent work shown that have been experienced by Marguerite Duras, Jacques Rivette, or even Antonioni, Godard and Resnais.

The difference, of course, is largely one of economics, and it might seem unfair to single out Wollen and Mulvey as overrated figures when the audiences they command remain relatively minuscule. The point to be made is that the needs of one kind of audience are being at least partially met, while the needs of a much broader audience are being chiefly thwarted. And woe indeed to the experimental film-maker unlucky enough to be trapped between those pre-defined to single audiences and categories, who can’t be assimilated at all.

***

To adapt the titles of two of the more humorous and accessible avant-garde films, George Landow’s 1969 Institutional Quality and Mark Rappaport’s 1973 Casual Relations, avant-garde film- making today seems ruled by two distinct and sometimes contradictory forces: Institutional Qualities and Casual Relations. Institutional Qualities are all those facets of avant-garde films which makethem acceptable to institutions -– the degrees of formal interest, seriousness and experimentation and the relative modesty of budgets that allow them tobe discussed in us avant- garde journals like Millennium Film Journal and October, screened in avant-garde showcases and generally admitted to the fold. Casual Relations, on the other hand, are those much less predictable and orderlytransactions that take place between films and spectators — the spontaneous and often instinctive (rather than taught) responses that occur whenever unconventional fare is shown. Consequently, if the avant-garde film today might be regarded as a two-headed beast (as divided, in a way, as critics A and B), one of those heads is upright, responsible and civilised, the other unruly, wayward and potentially savage. Most of the major avant-garde film-makers, from Stan Brakhage to Michael Snow to Godard and Rivette, manage to straddle both categories.

***

Does the avant-garde film still exist? Ask a member of the avant- garde film community and you might as well be asking whether air still exists. Ask anyone else, and the question is more likely to take on a modicum of sense. On one level, as a continuing tradition, its survival, however precarious, can’t be questioned. But as a functional term for identifying a particular sphere of interest, its use often becomes deceptive.

‘When people say “the avant-garde,’ says Mark Rappaport, ‘they often seem to be talking about a category, a sub-genre, rather than work that breaks new ground or takes great risks.’ (Something of a risk-taker himself, Rappaport has turned out five low-budget, unconventional narrative features since 1973, and has managed to acquire a considerable reputation in spite of the fact that none of the films has fitted comfortably within either an avant-garde or an ‘art film’ framework.) ‘Avant-garde used as a description automatically bestows legitimacy and establishes reverence towards the subject, suggesting that it’s considerably better than it is. It’s an overworked word that usually applies to the most rarified coterie art. Sixty years ago, people would never have described themselves as avant-garde musicians or film-makers. Now there is a kind of false pride and unearned elitism in being tagged as an avant-garde film- maker. Is anyone more “avant-garde” than Hitchcock, Dreyer or Buñuel, to this very day? I have yet to be convinced.’ ‘My image of the avant-garde is, I guess, like everybody’s, ‘ says Leslie Thornton (whose work, like De Landa’s, gets shown almost exclusively within avant-garde formats).‘’It’s the Dada era. That’s when it really meant something, when there was a real awareness of what it was about. A lot of very good work — the manifestos, the critical work and the artwork — was produced in a short period. It wasn’t a comfortable time. Now the avant-garde, once it’s identified, is always immediately in a comfortable, accepted position. It’s almost impossible not to be. ‘There’s no question about the integrity of Stan Brakhage’s work and what he has accomplished; what he has identified as problems of expression using cinema. But he is the one who had the insight to make things happen on the line. And those people who emulate Brakhage, who identify his practice as the correct practice for the avant-garde, are not doing it; they’re not functioning on that level. By making Brakhage a historical figure, you’re negating his practice — at least in the kind of terms that I envisage it. So the people who would be practicing within an avant- garde mode today is the ones who make the practice as difficult as he did, in his time. And that’s probably not an easy thing to do now, for all sorts of reasons.’

Rappaport has problems of his own with exclusive definitions: ‘I remember Jonas Mekas saying a few years ago, when he was still writing for the Village Voice, that there was only one avant-garde — implying, of course, that to be avant- garde was a great deal holier than not to be. And that avant-garde concerned itself wholly with structuralism. In short, it was a frozen concept; academia and avant-garde became synonymous. Once it becomes one thing and is not capable of being anything else, the concept is completely dead and useless. Some film critics still seem to think that warmed-over minimalism and self-referential film-making is avant-garde, instead of the avant-garde being that elusive cutting edge, the wild side that has not been fully understood or explored or explained. In music, when the New York Times uses the word ”avant-garde,” it’s to describe those composers whom the public don’t seem to want to listen to. I’m afraid that avant-garde in the film world usually has the same connotations as your basic kiss of death.’

Sometimes, however, the meanings and implications of a term can shift when you move from one place to another. Leslie Thornton, after many years based in New York and Connecticut, has recently been teaching experimental film production in San Francisco, where she notes that the intellectual climate is appreciably different. ‘Because there’s less going on, people seem more engaged. They want to make an effort; there are more private screenings; someone just expresses an interest and you end up showing film in a living room, or you go somewhere else to talk after a screening. If that happens in New York, it’s very hidden. In New York, people say something like, “Oh yes, I’ll be there, but I’m not, uh, in any condition to talk to you about it afterwards.” It’s always an effort, even with your closest friends. I make the work as a kind of site for some exchange –- it’s meant to instigate something. That is part of the reason it happens, for me. And then nothing happens at the other end. It never works out in New York. But Steve Anker, who run the Cinematheque in San Francisco [another New york transplant, one should add], has very quietly been an influential force; he really nurtures an environment of exchange.’

Looking round at the experimental kinds of film-making being done, it seems possible to trace certain common preoccupations and traits in some of the most disparate works. Much of the work by men, for instance, seems to concentrate on male possessions: this is my house; my wife, my home town, my country, my hangups. A good many of the women seem more concerned with questions of identity and mirrors. Film-makers as different as Chantal Akerman and Michael Snow, Louis Hock and Jean-Luc Godard, seem to be dreaming up ways of making their procedures more widely accessible, while more intransigent figures such as Leslie Thornton, Yvonne Rainer, Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet seem to be working their way ever closer to the cutting edge of their own difficulty. But one thing that unites very few of them, and proves less than helpful in paving our way to most of them, is the appellation ‘avant- garde’. If we wish to speak of them in the same breath, it looks as though we will have to find another strategy for defining what they are.