From a 1989 catalog that I did for the Walker Art Center, Cinema Outsider: The Films of William Klein. — J.R.

William Klein on His Film Work

Klein made the following remarks in a telephone conversation with Jonathan Rosenbaum in early November 1988.

On Broadway by Light (1958) and Orson Welles

I did this book on New York: black-and-white, grungy photographs. People said, ‘What a put-down — New York is not like that. New York is a million things, and you just see the seamy side.” So I thought I would do a film showing how seamy New York was, but intellectually, by doing a thing on electric- light signs. How beautiful they are, and what an obsessive, brainwashing message they carry. And everybody is so thankful for this super spectacle. Anyway, I think it’s the first Pop film.

Afterwards, I went from New York to Paris on a boat. We were on the pier with all our suitcases when I saw Orson Welles with a cigar and a little attaché case – that’s all he had as luggage. I went up to him and said, “Listen, I’ve just shot a film. Would you like to see it?” I showed it to him in the boat’s movie theater, and he said, “This is the first film I’ve ever seen in which the color is absolutely necessary.”

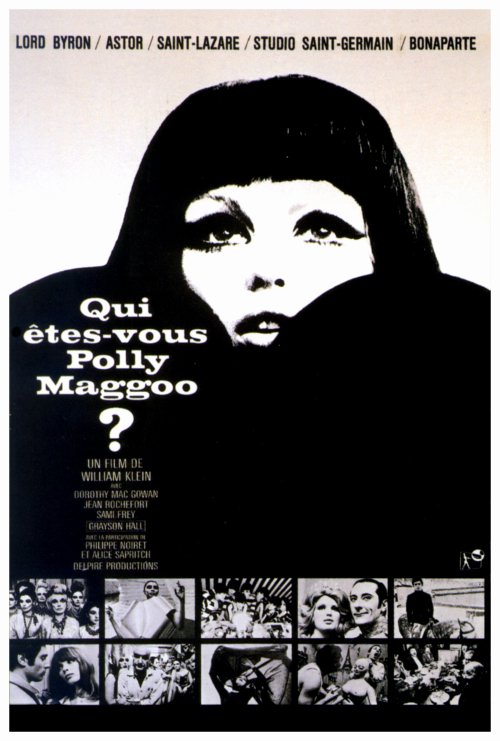

On Qui etes-vous, Polly Maggoo? (Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?) (1965-1966) and Stanley Kubrick

Kubrick saw Polly Maggoo in his private screening room. Then he wrote me a letter saying that the film was ten years ahead of its time, that he related to it very strongly, and that he felt we had a great deal in common. I was very pleased by this letter. I was just getting ready to do Mr. Freedom, and I wrote back immediately, saying that I was trying to raise money for my new film. And I never got an answer! I like Kubrick a lot, actually. Very few people know that he started out as a photographer. In fact, his first film, a short with a boxer, was an extension of a picture story that he did for Look magazine; I remember having seen it when it came out.

On Mr. Freedom (1967-1 968)

A lot of French critics said it wasn’t realistic. The idea of grotesque stylization wasn’t accepted. But now, if you want to win an argument about a film, you can always say it’s a comic strip reference. It was shot at the end of ’67 and the beginning of ’68, but the French government censored it for nine months, thinking it was about May ’68. So it didn’t come out until ’69. Anyway, it was completely foreign to the whole movie scene here in France. I guess my position is pretty marginal everywhere — then and now.

On Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther (1970)

The original title was The State of the Union. It was something l did in my schizo-militant period, an agit-prop film. I filmed Eldridge Cleaver for three days and three nights, practically nonstop, with hashish floating out the window. I have about an hour of edited film where he is shown as totally irresponsible, which he later revealed himself to be. But at that time, I was on a binge after having done Festival Panafricain (1969). He was at the Algiers festival, saw what I was doing, and asked if I would do a film on him. He said reasonable and unreasonable things, but in my zeal to make a statement — and also because it was an Algerian government production — I censored the craziness. I’d like to do sequels to both Muhammad Ali and Eldridge Cleaver, you know.

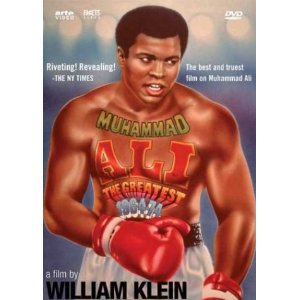

On Muhammad Ali the Greatest (1974)

You know, when I did the first film on Ali in 1964 he was Cassius Clay, and I called it Cassius le grand. Well, I was practically the only one from the media in his camp. The white press was scared to death and hypnotized by the bad mother. To them. Cassius was the clown and didn’t have a chance. They were wrong. In Zaire, in 1974, they were saying that George Foreman was unbeatable and that Ali was over the hill. I was scared myself. But Ali was something else.

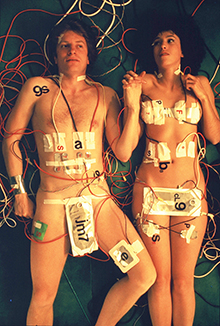

On Le couple témoin (The Model Couple) (1975-1976)

I had a big project I wanted to do around 1973. The French had these delusions of grandeur inherited from De Gaulle. They wanted to make, out of nothing, new cities, and I wanted to show how ridiculous all this was. I never got the money to make this film, but I had a government advance. So I developed just a part of it about this model couple in a model apartment who were being tested night and day — a science fiction farce. The couple were Anémone and André Dussolier; it was her first commercial role and one of his first parts as well.

On The Little Richard Story (1980)

Why did Little Richard walk out of the film? Well, there was this outfit that had the idea of hawking Bibles to unions for members who died, so instead of sending flowers they would send these thirty-, forty-, or fifty-dollar Bibles. At one point they planned a black-heritage Bible. Little Richard was down and out at the time, and he dreamed of being a black Billy Graham. so the Bible people put him under contract for all media work. When the film was to be done, they were to produce Little Richard. In the middle of the shooting he decided he wasn’t getting enough money; he took off, and the Bible men sent detectives all over the country to find him. They never did. For me, getting involved in that situation was like riding a bike blindfolded.

On Mode in France (1985)

There are thirteen sequences, and I tried to do each one in a different movie style. With the fashion designer Jean-Paul Gautier, I did a fake documentary about street-singing, clichéd Paris in which he dressed a whole neighborhood of a few hundred people — in the marketplace, the whores and the pimps, everyone. Another sequence was like a B-movie thriller. In one sequence with the designer Alaïa I used Grace Jones and the model Linda Spierring; they played a scene from Marivaux with their dresses changing after every sentence. Another section became True Confessions: everything looked like a magazine spread. About thirty girls were put in a white box with exaggerated perspectives. And there was another part in a gigantic sex shop where fashion was treated as an under-the-counter commodity — girls performing in peepshows, and so on. It was a film that actually made me some enemies in the fashion world (laughs). Those who didn’t think I took them seriously enough.