Written for Sight and Sound‘s blog in July 2011. — J.R.

Not exactly a film festival or a conference in the usual sense, Il Cinema Ritrovato has many of the benefits of each without their professional drawbacks -– namely the frantic boom-or-bust atmosphere promulgated by the entertainment press at Cannes, and the relative dullness and institutional oppressiveness of a long succession of academic papers.

A relaxed yet intense eight-day bash devoted to film restorations, Il Cinema Ritrovato is held over some of the hottest days of the summer in the oldest university town in Europe, and sponsored by one of film restoration’s leading institutions, the Cineteca Bologna, which boasts the rejuvenation of Charlie Chaplin’s works among its achievements. Frequented chiefly by teachers, students, archivists, programmers, film historians and various others involved with restoration (such as people working for various DVD labels), the events are usually split between three auditoriums in the daytime –- although this year a fourth screen was added, making for many more choices as well as conflicts -– followed by huge, free outdoor screenings for everyone in the Piazza Maggiore every evening.

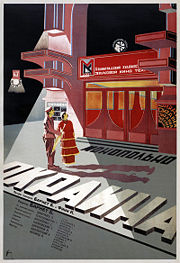

Whether the individual attractions are populist (among the Piazza restorations this year were Nosferatu (1922) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925) with full-scale orchestral -– and in the latter case vocal -– accompaniments, Les Enfants du Paradis (1945), the 1940 Thief of Bagdad and Taxi Driver (1976) or more specialized (some of this year’s retrospective subjects were Boris Barnet, Albert Capellani, early Howard Hawks, Elia Kazan and educational documentaries by Eric Rohmer, Maurice Tourneur and Conrad Veidt), the opportunities to reevaluate film history are plentiful. Even when one has to cope with such obstacles as earphone translations that obscure the artful uses of sound, as in Barnet’s astonishing first talkie, the 1933 Outskirts (Okraina), the opportunities to see rare materials in informed contexts are invaluable. And the musical accompaniments provided for the silent pictures are generally exquisite.

For those who had previously encountered Barnet only through his early features, it was energising to discover the same gusto for ornery traits in ordinary people already evident in Outskirts and By the Bluest of Seas (U Samovo Sineyvo Morya, 1935; see first still below) still coursing through his wartime films –- features and shorts alike. Standouts included the 1943 Slavni Mali (A Good Lad, aka Novgorodtsy), the 1945 Odnazhdi Noch (Dark is the Night), and eccentric postwar works The Wrestler and the Clown (Borets i Kloun, 1957; see above still at the head of this article) and Alyonka (1962), both in vibrant color.

The propensity of some characters in the midst of melodramatic situations to burst into song may be more a trait of Soviet cinema in general than one of Barnet in particular (one also finds this happening, for instance, in Dovzhenko’s 1935 Aerograd), but this only suggests that the context still needed for westerners to properly understand this historical patch of cinema has not yet arrived, and Barnet remains an especially mysterious figure within it.

In the case of Hawks, many potential critical conclusions could be drawn from the screened evidence. One, the noncontroversial judgment –- articulated by Kevin Brownlow at a panel discussion I also participated in -– that the director only discovered his artistic identity in the fullest sense during the sound era.

More specifically and personally, though, rewatching Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and Land of the Pharaohs (1955), it was startling to discover that these two garish spectacles offered two versions of the same villainess –- a jewelry-obsessed femme fatale played by Marilyn Monroe in the first and by Joan Collins in the second. The crucial and telling difference is the camaraderie felt and expressed by Lorelei Lee (Monroe) for Dorothy Shaw (Jane Russell) in Gentlemen, the only trait that prevents Lorelei from registering as a total monster.

Yet in a silent program devoted to the incomparable Musidora (1889-1957), head of the criminal gang in Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1915), the femme fatale was no less complex. One Feuillade two-reeler showed her reading the novelization of Les Vampires, then persuading an oafish admirer to pull off his own burglary; and in La Tierra de los Toros (1924), which she also directed, she plays herself trying to coax a Spanish bullfighter to play in her own film.

Given the relative freedom of Il Cinema Ritrovato from marketplace or careerist concerns, a certain amount of grumbling could be heard this year among the visitors about both the surfeit of choices offered by the fourth screen and some of the high-profile selections drawn from Cannes this year by Cineteca director Gian Luca Farinelli, such as Michel Hazanavicius’s silent-film pastiche The Artist and Angelina Maccarone’s documentary portrait of Charlotte Rampling (who turned up in Bologna for the screening) The Look (A Self Portrait Through Others).

I saw both of these for the first time in Bologna, and had a much easier time with the latter than the former, even while conceding that neither has much to do with the archival or canonical matters that govern the usual selections. (The distinction I find between the legitimacies of these two films may just be a matter of temperament and orientation; I’m not enough of a postmodernist to feel that the sadness of the end of the silent cinema can be adequately expressed by Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo score, but some knowledgeable colleagues clearly disagree.)

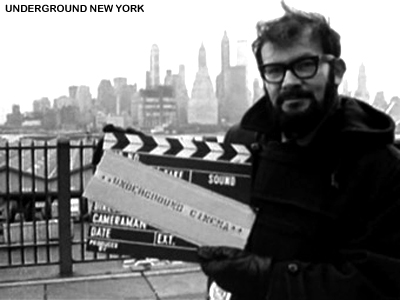

Admittedly, these were only two of the festival’s seven ‘special events’ – a lineup that also included such splendid (and noncontroversial) offerings as Gideon Bachman’s 1967 Underground New York (a priceless period chronicle unearthed from German television, enhanced by Bachman’s passionate account during the subsequent discussion of his own peripatetic career) and Peter von Bagh’s 2010 ‘Drama of Light’, the second half of Sodankylä Forever, a fascinating film diary by Il Cinema Ritrovato’s artistic director about the other annual summer event he directs. Even so, the multiplication of competing events and the corresponding reduction of repeat screenings left everyone feeling a little bereft in the midst of all the riches.