This appeared in the October 1974 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. This was long before the silent version of Blackmail was rediscovered and restored. — J.R.

Blackmail

Great Britain, 1929 Director: Alfred Hitchcock

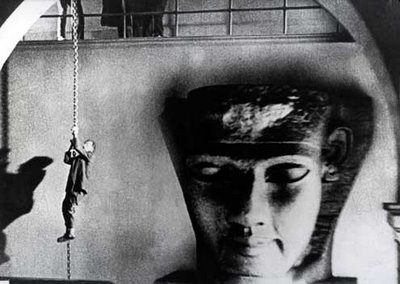

The extraordinary plateau attained by Hitchcock’s first sound film in relation to his overall development is the sum of many accomplishments: above all, a decisive mastery in moving back and forth between objective and subjective narrative modes. If the point-of-view is one of the cornerstones in Hitchcockian syntax, the film quite likely represents the first time in the director career that it is woven so seamlessly into a plot that all notions of stylistic “touches” gives way to a sustained psychological density. Beginning virtually like a documentary, Blackmail provides a quick foretaste of subjective truth in its early glimpses of the anonymous criminal, which subtly veer from the police’s viewpoint to his own – shifting, that is, from one kind of fear and apprehension to another. The complex overtones and ambiguities of the film are informed throughout by this kind of duplicity and intimacy, which oblige us to identify with rapist along with potential victim, murderer along with corpse, and detective along with blackmailer, at the same time as we are asked to regard them all with a certain amused skepticism. The shifting trajectories composing the plot work hand in glove with the moral ambivalences. After taking us from police to criminal and back again, the film directs us to a single policeman (Frank [John Longden]), abandons him to trace his girlfriend’s infidelity, invites us to “participate” in both her potential ravishment and her act of murder, then in her sense of guilt (starkly delineated in a neon sign, London streets at dawn, a beggar’s outstretched hand, and the idle chatter of a neighbor – each brilliantly rendered as a subjective impression echoing the crime), next encourages us to identify with her and Frank when Tracy appears, only to shift to Tracy himself as he is hounded to his death, and at last reverting to the couple again. But even they are supplanted by the final image: the mocking face of a joker in one of the artist’s paintings, making its last appearance as the police carry the canvas away. This leitmotif might recall (or anticipate) the sardonic disdain expressed for all the characters in Hitchcock’s late work, but the irony here is never allowed to block compassion. It assumes as much a leavening as a leveling function, often ridiculing heroes and humanizing villains in single strokes – as in the cut from the satisfied police inspector ordering Tracy’s arrest to Tracy himself, seen in an identical posture and looking equally satisfied as he polishes off a free meal served by Alice. Such equations (and the film has many) suggest a moral framework similar to that in subsequent films by Renoir, where everyone has his own reasons. Renoir is further evoked in the remarkable spatial continuity and depth maintained in the shop and connecting dining room, the frequent use of off-screen sound as counterpoint to image (Alice’s cries of distress in the studio heard over a shot of an oblivious policeman outside, previously glimpsed by her as an assurance of safety; Tracy’s leap through the dining room window audible before a pan makes it visible), and even the sensually nuanced performance by Anny Ondra -– dubbed during the shooting by Joan Barry – who frequently recalls Winna Winfried in La Nuit du Carrefour. More generally, Renoir’s universal perspective is matched by Hitchcock’s expert cross-fertilization of various stylistic strains in the silent cinema: the camera movements and expressionism of Murnau, the surrealist object (e.g., the giant Egyptian mask in the British Museum) in Clair and Buñuel. Hitchcock wasn’t able to film the ending he wanted – the arrest and incarceration of Alice, which was intended to “double” the opening sequence –- but he established another symmetrical pattern in its place. Beginning and concluding the story proper with Alice and a constable laughing together (which initially marks the transition from “silent” film with music and sound effects to full-blown talkie), he carries us from the general to the specific and back again, framing his plot within a pirouette. For the record, the version of under review contains two minor if irritating technical blemishes: occasional shifts and dubious stretches in the sound’s volume that seem accidental rather than intentional (including an awkwardly over-recorded bird song heard in Alice’s bedroom), and a short break in continuity in the build-up to the rape, which has the appearance of a censor’s cut.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

— Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1974 (vol. 41, no. 489)