From the Chicago Reader (December 9, 1988). — J.R.

THE NAKED GUN: FROM THE FILES OF POLICE SQUAD!

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by David Zucker

Written by Jerry Zucker, Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, and Pat Proft.

With Leslie Nielsen, George Kennedy, Priscilla Presley, Ricardo Montalban, O.J. Simpson, and Nancy Marchand.

Unlike some of my colleagues, I find the latest comedy by David Zucker, Jim Abrahams, and Jerry Zucker (the ZAZ team) a notch below their previous Airplane! (1980) and Top Secret! (1984). This shouldn’t matter much to anyone looking for an irreverent, anything-goes farce with a fair number of laughs; The Naked Gun is certainly that, and I don’t intend for the following to scare anyone away from it. But I do want to consider what’s been happening to the ZAZ team’s distinctive brand of satire over the past eight years.

All three ZAZ movies use as their point of departure the crystallized form of some bad formula movie. The lead characters wear deadpan expressions through their cliche roles, and the laughs derive largely from non sequiturs in their dialogue and from lunatic gags that surround them as they trudge through their routine plots, impervious to the silliness.

Airplane! stuck to this pattern pretty consistently, lampooning the disaster blockbusters of the 70s like Earthquake, the Airport sequels, and The Towering Inferno. An early (1957) and mainly forgotten version of the genre known as Zero Hour served as the filmmakers’ model, and an effective use of familiar noncomic stock actors — Robert Stack, Lloyd Bridges, Peter Graves, and Leslie Nielsen — helped spike the satire.

In 1982, the ZAZ team created an ill-fated TV series, Police Squad!, which I haven’t seen and which was taken off the air after four episodes. (Elements from this show, including its lead actor Leslie Nielsen, were later recycled in The Naked Gun.) Then came Top Secret!, which complicated the approach of Airplane! by anachronistically merging two dissimilar and outdated movie formulas — the Elvis Presley rock musical and the World War II epic — and adding elements from cold war thrillers like Torn Curtain for good measure. This second feature also mined a vein of visual and verbal non sequiturs that bore no particular relation to either of the lampooned genres (for example, a painting of a landscape seen from a moving train was rendered as a blur). This vein, which already existed embryonically in Airplane!, developed into a zone of surreal whimsy and sheer weirdness that was often indulged in simply for its own sake.

Some of the funniest conceits in Top Secret! are in effect combinations of familiar movie conventions with weird, off-kilter variations. A phone looming gigantically in the foreground of one shot proves to be in fact a giant phone (rather than a visual trick of perspective) when a character approaches the camera to answer it; the offscreen sound of a German song over a shot of a horse-drawn carriage turns out to be coming from the horse; in the midst of a German torture session, one hears the following exchange: “Do you want me to bring out the Leroy Neiman paintings?” “No. We cannot risk violating the Geneva Convention.” Unfortunately, Top Secret!, which is more daring and adventuresome than Airplane, proved to be much less successful at the box office. (The relative absence of familiar, old-time Hollywood faces in the cast, apart from Omar Sharif and Peter Cushing, probably contributed to the audience’s disorientation.)

The disappointing performance of Top Secret! undoubtedly led to a certain retrenchment, the first sign of which was Ruthless People (1986). A relatively successful kidnapping farce, produced and directed by the ZAZ team but written by Dale Launer, Ruthless People had at most only a cursory relation to Airplane! and Top Secret! The second sign of retrenchment is The Naked Gun, which resumes the lampoon cycle in a somewhat more diluted form. The new movie, which restricts its exclamation point to its subtitle, also restricts its satire in relation to its predecessors. Roughly half the movie lampoons the routine made-for-TV cop film or its movie-house equivalent; the other half lunges randomly after every laugh-getting device the filmmakers can think of — most of them more slapstick than satire. Weird ideas are kept to a minimum.

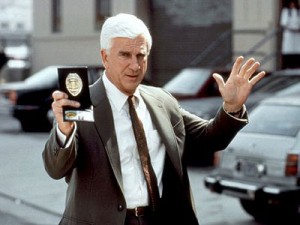

The principal satiric device in The Naked Gun is Leslie Nielsen going through his standard inventory of stolid responses — a kind of wood-block acting that has been his stock-in-trade ever since he starred in Forbidden Planet 32 years ago. Here he plays LA cop Frank Drebin, thickheadedly matching his wits against wealthy villain Vincent Ludwig (Ricardo Montalban) — who, for reasons that remain obscure to me, is plotting the assassination of Queen Elizabeth II (played by look-alike Jeannette Charles) at a California Angels baseball game. On the side Drebin suavely romances Ludwig’s secretary Jane Spencer (Priscilla Presley).

Although The Naked Gun is every bit as irreverent as Airplane! and Top Secret!, there are moments when its irreverence shades off into mere crudity and/or cruelty, although viewers will have different thresholds determining where these moments are. I was a little put off by the pre-credit sequence set in Beirut, where stand-ins for Khomeini, Khadafy, Amin, Nasser (known as Yasser), Gorbachev, and Arafat meet to plot anti-American acts of terrorism. Drebin (whom we later learn is in Beirut on vacation) emerges from a disguise to punch them all out and declare, “Don’t ever let me catch you guys in America!” As slapstick nonsense, this isn’t as bad as it sounds, but I can’t quite share the sentiment of Variety‘s reviewer, who remarks that the “scene ends so ludicrously, one only wishes it could come true.”

This is followed, after the credits, by a funnier sequence in which Drebin’s fellow police detective, Norburg (O.J. Simpson), intercepts a shipment of heroin in Los Angeles Harbor. Sneaking aboard a ship called I Luv You (the basis for some future gags), he attempts to kick open a door, and his foot goes straight through it. Inside the cabin he’s greeted by a horde of lowlifes, one of whom shoots him. Staggering from the impact, he bumps into a wall, falls against wet paint, gets injured by a falling window, collides with a wedding cake, steps into a bear trap, and finally falls overboard — a kind of protracted cruelty joke that sets the pace for much of what’s to come. (Cruelty jokes appear to be unusually fashionable this holiday season; the evocation of stapled mice ears in Scrooged gets one of that film’s biggest laughs.)

The fact that Nielsen is 62, George Kennedy (who plays the police captain) is 63, and Montalban is 68 contributes to their inadequacy as “serious” male leads, but not in ways that I find invariably funny. (For cruel humor, I much prefer Nielsen and Presley’s joint admission that they both practice safe sex, followed by a shot of them groping at one another in full-size body condoms.) My favorite moment occurs at the climactic baseball game — a very funny sequence, most of which has nothing to do with bad cop movies — when Nielsen executes a manic two-step on the field worthy of some of the better spastic choreography of Jerry Lewis; it’s a pure flight of fancy that has nothing to do with the rest of the movie, executed with elation.

My quarrel with the rest of the movie has more to do with the script than with its execution. (David Zucker’s solo flight as director is by and large as polished as his previous directorial collaborations with Jim Abrahams and Jerry Zucker.) One of the central plot devices borrows the notion of the hypnotized zombie killer from the recently rereleased The Manchurian Candidate (1962) — another example of the movie’s tendency to grab at everything in sight rather than limit its focus to one (or even two or three) genres. On the other hand, there are plenty of guest-star cameos to take up the slack created by this scattershot approach; perhaps the best of these is offered by the late John Houseman (he also crops up in Another Woman and Scrooged), whose bit here as a driving instructor shouldn’t be missed.

For the next ZAZ lampoon, I’d like to see a takeoff on the “serious” Woody Allen art picture. Here’s a form of bad movie that is certainly long overdue for a dry cleaning, and as long as Allen refuses to make any more comedies himself, the field is wide open.