From American Film (April 1982). — J.R.

The Film in History: Restaging the Past by Pierre Sorlin. Barnes & Noble, $21.50.

Feature Films as History edited by K.R.M. Short. University of Tennessee Press, $16.50.

Vietnam on Film: From “The Green Berets” to “Apocalypse Now” by Gilbert Adair. Proteus, $13.95.

What is a historical film? Sociologist and cultural historian Pierre Sorlin concludes a comparison between two French films about the French Revolution released during the mid-thirties — Abel Gance’ s Napoleon Bonaparte and Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise — with a succinct formula for his provocative working assumption in The Film in History. “A historical film,” he writes, “is a reconstruction of the social relationship which, using the pretext of the past, reorganizes the present.”

It’s an interesting notion to try out on all the films that we regard as historical. To get a proper fix on Reds, for instance, one has to consider not only the years 1915 to 1920, during which the portrayed events take place, but also the much more immediate past, during which the movie was being formulated and put together, and the present, during which it is being seen and understood. Thus the relatively short shrift paid in the film to class differences – a fundamental issue in John Reed’s life — can be ascribed in part to the basically middle-class orientation of the student revolts in the sixties, which have a lot to do with the way that we currently regard radical politics. Similarly, part of the disillusionment with the Russian Revolution expressed in the second half of the film clearly comes to us courtesy of the cold war; and although Reed’s train journey to the congress of eastern peoples in Baku in 1920 is a matter of historical fact, the film’s handling of this episode inevitably alludes to our more recent memories of Afghanistan and Iran.

Sorlin is never mechanical about juxtaposing historical dates with the dates of a film’s production and reception, but he does help us to understand that until we’ve answered the question of what we expect to learn or gain from history in the present, any consideration of history, per se, is bound to be somewhat loaded with our unacknowledged biases.

In reading Sorlin’s book — the most substantial of those under review — it is important to understand that his concerns are the reverse of those espoused by auteurist critics. The names of Gance and Renoir don’t figure once in his discussion of Napoleon Bonaparte and La Marseillaise, which enables him to be as sensitive to these films’ similarities (having to do with “actors and circumstances” and a thirties sense of political change) as he is to their differences.

At the same time, no one could accuse Sorlin of shortchanging aesthetic factors. He is as alert to compositions, camera movements, and cuts as expressive entities as he is to characters and plots. But he’s more concerned with each film’s social impact than with its personal overtone. Examining The Birth of a Nation in conjunction with Gone With the Wind, he points out that although D.W. Griffith had his own reasons for restaging the Civil War, “he did not make the film single-handed,” and “the thousands of Americans who saw the film and enthused over it did not care about Griffith’s ‘purpose.’”

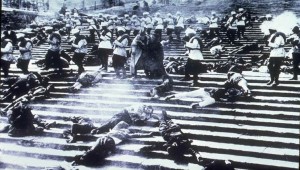

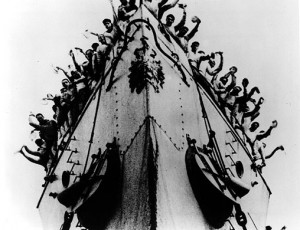

The Film in History, adapted from a lecture course taught at Oxford University in 1976, has the uncharacteristic advantage of having a lot to say to general readers as well as to historians. By contrast, K.R.M. Short’s collection of essays by seven historians (three of whom, incidentally, attended Sorlin’s course). Feature Films as History is addressed mainly to academics, while Gilbert Adair’s well-written survey of American films about Vietnam, Vietnam on Film, eschews footnotes and bibliography to concentrate on a critical approach designed for nonspecialized readers. For nonhistorians, the most interesting forays in the Short anthology are a detailed comparison by D. J. Wenden of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin with the substantially different historical incidents that inspired it; Thomas Cripps’ s “Casablanca, Tennessee lohnson, and The Negro Soldier -– Hollywood Liberals and World War II”; and the editor’s own introduction, which usefully outlines many of the research options and problems facing any historian who wishes to study films.

Copiously illustrated with stills, Adair’s Vietnam on Film is strongest in the area where Sorlin’s book is weakest — namely, the gracefulness of its prose style. (Although Sorlin is French and usually writes in his native tongue, The Film in History is not a translation; his English usually remains serviceable without attaining any elegance.) Indeed, given Adair’s usual penchant for wordplay and aphorisms, as an aesthetically oriented critic for film magazines like Sight and Sound and Film Comment, it is surprising to see him tackling the sort of subject matter that would appear to be foreign to his taste and talents. Yet precisely for this reason, his book exhibits certain virtues that ate relatively unexpected in a made-to-order book of this kind — wit, a feeling for nuance, and the kind of carefully chiseled writing that usually guarantees a good read.

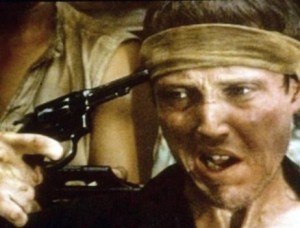

The best parts of this book are his chapters on The Green Berets, The Deer Hunter, and Apocalypse Now -– scrupulous point-by-point assessments that are as alert to moral questions as to aesthetic ones, shaped by an overall vantage point that could be described as English liberal-humanist (certainly not “anti-American,” as a reviewer in Variety complained). But when Adair feels called upon to synthesize his individual insights, the results are sometimes forced; his comparison of the Vietnam film with pornography and of Apocalypse Now with the “full frontal” seems especially unedifying. And his survey chapters have a tendency to flit past the consciousness the way that most surveys do.

At the end of an astute evaluation of The Deer Hunter, though, Adair arrives at a conclusion which might be said to relate closely to Sorlin’s starting point: “Such movies as The Green Berets and The Deer Hunter should perhaps be seen less as about the Vietnam War, in which capacity their inadequacies are painfully evident, than part of it — part, at least, of how it was perceived by Americans — and any history of the period omitting them from its data will necessarily be incomplete.” And without pretending to either the depth or scale of a historian like Sorlin, Adair is deft in charting the surface of a moral dilemma — America’s involvement in Vietnam –- that Hollywood has tended either to ignore (as in The Deer Hunter) or distort (as in Apocalypse Now).