From the Chicago Reader (December 21, 2001). — J.R.

The Affair of the Necklace

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Charles Shyer

Written by John Sweet

With Hilary Swank, Adrien Brody, Jonathan Pryce, Christopher Walken, and Joely Richardson.

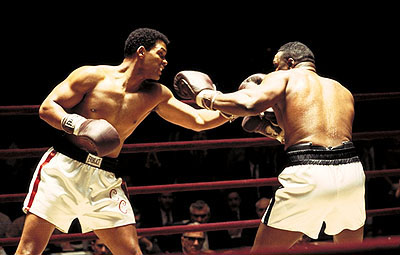

Ali

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Michael Mann

Written by Gregory Allen Howard, Stephen Rivele, Christopher Wilkinson, Eric Roth, and Mann

With Will Smith, Jon Voight, Mario Van Peebles, Jamie Foxx, Ron Silver, Jeffrey Wright, and Giancarlo Esposito.

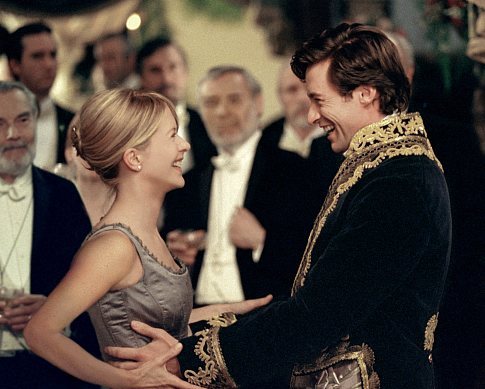

Kate & Leopold

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by James Mangold

Written by Steven Rogers and Mangold

With Meg Ryan, Hugh Jackman, Liev Schreiber, Breckin Meyer, and Philip Bosco.

Kiss Me Kate

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by George Sidney

Written by Sam and Bella Spewack and Dorothy Kingsley

With Howard Keel, Kathryn Grayson, Ann Miller, Bobby Van, Keenan Wynn, James Whitmore, and Bob Fosse.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

*** A must see

Directed by Peter Jackson

Written by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, and Jackson

With Elijah Wood, Ian McKellen, Liv Tyler, Viggo Mortensen, Sean Astin, Cate Blanchett, and John Rhys-Davies.

The Majestic

Rating 0 Worthless

Directed by Frank Darabont

Written by Michael Sloane

With Jim Carrey, Martin Landau, Laurie Holden, David Ogden Stiers, James Whitmore, and Jeffrey DeMunn.

The Royal Tenenbaums

*** A must see

Directed by Wes Anderson

Written by Anderson and Owen Wilson

With Danny Glover, Gene Hackman, Anjelica Huston, Bill Murray, Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, Luke Wilson, and Owen Wilson.

Vanilla Sky

** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Cameron Crowe

With Tom Cruise, Penelope Cruz, Cameron Diaz, Kurt Russell, Jason Lee, and Johnny Galecki.

An irate reader wrote to the paper last week complaining that he could never tell from my reviews whether I was recommending a movie or not. I don’t know which reviews he had in mind, but I’m willing to plead guilty as charged, at least in principle. Recommending particular movies is something I can do for friends or relatives, but trying to make recommendations for strangers — even though plenty of critics do — seems a little presumptuous. Why should strangers give up their own tastes and accept my interests and limitations as their own? I also have a problem with a reviewing policy that assumes all viewers should see the same movies; I firmly believe that people should have a wide range of choices and that they should choose among them according to their own desires. So I give ratings, descriptions, and evaluations of movies — including the eight Christmas choices listed above, and considered in alphabetical order — in the hope that readers will use them selectively and critically, weighing their biases against mine.

I wasn’t looking forward to the latest star vehicle of Hilary Swank (who won an Oscar for her role in Boys Don’t Cry), an opulent intrigue set in 18th-century France, or to any movie directed by Charles Shyer (whose credits include Baby Boom, the remake of Father of the Bride, and Father of the Bride Part II). Seeing his The Affair of the Necklace didn’t rouse me out of my apathy, even though it has Christopher Walken camping it up as the magician-alchemist-charlatan Count Cagliostro, Joely Richardson as Marie Antoinette, and Jonathan Pryce as a corrupt and depraved cardinal. If you were my friend I’d advise you to save your money, but that doesn’t mean that some of you won’t find the film worthwhile.

I did, however, have a fine time at Ali, partly because I expected to. I’m even more indifferent to boxing than I was to the prospect of Swank and Shyer telling me something about 18th-century France, but I’m fascinated by the spiky, creative personality of Muhammad Ali, especially during the ten-year period covered by this film (1964-’74). And I know that director Michael Mann has an unusual ability to make long-winded movies absorbing. Ali, which runs almost three hours, eventually loses its focus, and by the time it was over I was hard put to say exactly what it was about, apart from the perils of rebellion. But I was never bored. I was particularly struck by Mario Van Peebles’s Malcolm X, a great improvement on the Hollywood-ized version offered by Denzel Washington and Spike Lee nine years ago; one scene in which Van Peebles’s Malcolm and Will Smith’s wonderfully realized and fully energized Ali compare their feelings of rage against southern racism and how these feelings have affected them physically carries more bite than anything in Lee’s Malcolm X. Some of this can undoubtedly be attributed to the script — credited to five writers, including Mann — but it’s also true that Mann’s epic directorial style allows for such moments.

I was also mightily impressed by Jon Voight’s impersonation of Howard Cosell (so uncanny I forgot I was watching Voight) and many smaller yet perfectly inflected turns, such as Giancarlo Esposito’s depiction of Ali’s father. One period detail in a flashback raised my eyebrows: a sign that said Coloreds Only; I spent my childhood in the jim crow south, and I only remember signs with the singular “colored,” which seemed calculated to make the people in mind even more abstract than any plural noun would have. But generally this is a high-level biopic, as impressive in detail as in its overall sweep.

Kate & Leopold belongs to a loose subgenre combining roughly equal amounts of time-travel whimsy, romantic comedy, and nostalgia for 19th-century Manhattan. (The first two are combined in, among other films, the 1980 Somewhere in Time, the first and third in Jack Finney’s popular novel Time and Again; both are probable influences.) An eligible 19th-century bachelor, Leopold (Hugh Jackman), gets transported to the 21st century by his great-great grandson — a science nerd (Liev Schreiber) who promptly falls down an elevator shaft, clearing the way for his girlfriend and downstairs neighbor Kate (Meg Ryan), an ambitious executive, to show the stranger around and fall in love with him. If you like the romantic leads, as I do, you probably won’t mind that Leopold adjusts to 134 years of progress — or devolution — with implausible speed, resourcefulness, and luck; if he has to borrow a horse to chase after a purse snatcher in Central Park, you can bet that a carriage driver on the street will happily lend him one in two seconds flat.

My favorite among these holiday offerings — Kiss Me Kate, one of the best MGM musicals of the 1950s not made by the Arthur Freed unit — is enhanced by being shown in 3-D and through a novel projection system involving the precise synchronization of two projectors and a magnetic sound track that guarantees the best sound and image this movie is ever likely to have. (Part of the credit should go to local projection virtuoso James Bond, who hooked it all up at the Music Box.) Fortunately, there’s an eyeful and an earful to make all this trouble worth the bother: George Sidney’s exuberantly vulgar direction, which makes more aggressive use of objects flung at the viewer than any other 3-D movie (apart from the early 80s ‘Scope Italian western Comin’ at Ya!) as well as fascinating uses of mirrors, windows, and neosurrealist stage decors evoking De Chirico and Tanguy; a modernist dovetailing of a stage musical version of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew with a bombastic feud between the formerly married leads (Howard Keel and Kathryn Grayson); some of the most exhilarating dancing to be found anywhere; and a fabulous Cole Porter score that manages to survive some Hollywood bowdlerizing. The best number, “From This Moment On,” wasn’t even included in the 40s stage version; here it’s performed by six dancers, including the very young Bob Fosse, who choreographed the number in a way that anticipates his full-blown style.

One could quibble, I suppose, about Grayson as Keel’s partner, but just about everyone else in the cast is delightful. Ann Miller, currently visible as the landlady in Mulholland Drive, achieves something close to her apotheosis in her tap-dancing; and James Whitmore, one of the few bearable elements in the new release The Majestic, here teams up with Keenan Wynn — playing hoods who resemble refugees from Guys and Dolls — to amiably (if amateurishly) hoof their way through the Porter tune “Brush Up Your Shakespeare.”

Since I’ve never read J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy and haven’t even dipped into The Hobbit since my childhood, I can’t say how faithful Peter Jackson’s big-budget 165-minute adaptation of the first volume, The Fellowship of the Ring, is. Nor can I claim to have been especially attentive to the narrative; as with Star Wars, pop myth and characters seem to count for more than story line. But I was impressed by the scale of the visual settings — which include real landscapes, sets, and uncanny amalgamations of the two — and the dreamlike and metaphysical appeals to the imagination made by the contrast between their vastnesses and the tiny human figures within them, which call to mind the fantasy locations of Mervyn Peake as well as Tolkien. For this reason alone, I was happier watching The Lord of the Rings than any of the chapters of Star Wars, becoming bored only during the battle scenes. But then my preference for nonnarrative over narrative in fantasy settings and my distaste for warfare may place me in a minority, which probably limits my usefulness as a guide to some viewers. (Based on what people have told me over the years, the war scenes in Star Wars provoke the most nostalgia and affection, apparently because they stimulated the most parent-child bonding; evidently, the family that slays together stays together.)

The most abject movie on my list, The Majestic, works overtime shamelessly constructing fantasies of goodwill out of vague memories of Frank Capra and even vaguer memories of the early 50s, when the story takes place. Mythically, it suggests Dorothy falling asleep in Oz and waking up in Kansas. An apolitical studio screenwriter (Jim Carrey) finds himself blacklisted and, having lost everything, drives idly up the California coast, suffers an accident and amnesia, and finds himself welcomed into the bosom of a small town as a missing-in-action World War II hero. His widowed father (Martin Landau), proprietor of the town’s now-closed movie palace, is inspired to resurrect the place, with the help of two faithful assistants, one a black usher who behaves like an obsequious servant — presumably to stir up nostalgia for even more remote periods.

Lurking behind the plot complications are plenty of fantasy assumptions. Among them: blacklist victims weren’t political (an absurd notion already indulged by Irwin Winkler’s Guilty by Suspicion); patriotic small-town populations — when they weren’t following war heroes around on the street and applauding when they kissed their girlfriends — were horrified by the communist witch-hunts; the witch-hunters could be cowed by the sincerity of apolitical vets speaking their mind; victims of amnesia still remember the movies they’ve seen because “movies aren’t part of one’s life”; and Ed Wood-ish B features (there’s a clumsy pastiche called Sand Pirates of the Sahara) played alongside A pictures such as The African Queen at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Surrounding these hypocritical howlers are all sorts of “knowing” insider details, beginning with a nice gag about Hollywood screenwriters that starts the picture and concluding with an ironic gag about Invasion of the Body Snatchers playing at the restored Majestic — some of which suggests that some script doctor tried to shovel in disrespectful wisecracks whenever possible. But the phonies triumph over such glancing demurrals.

Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums was the movie in this batch I was most looking forward to, and the one that most disappointed me. It repeats many of the stylistic tropes and bittersweet notions about adolescence from Anderson’s Rushmore — increasing the overall cute tone and the paradoxical, Salinger-esque sense of snobbish populism that was slightly problematic in the earlier film, without increasing the imaginative or emotional depth. Of course viewers who haven’t seen Rushmore shouldn’t have these problems, and most people would probably enjoy a lot of this movie anyway. Expectations count for a good deal in these matters, and if you’re merely looking for fun while learning about a dysfunctional family’s neuroses and their various forms of sweetness, you probably won’t feel let down.

Similarly, how you respond to Vanilla Sky may depend on whether you saw Open Your Eyes — the Spanish fantasy thriller of Alejandro Amenabar that played here four years ago. I mainly liked Open Your Eyes, but I’d forgotten enough of the plot details and twists that I could enjoy Cameron Crowe’s slick remake. I’m sure your opinion of Tom Cruise would play an equally important role in whether you can enjoy the film. I now find him tolerable only when he’s in a movie that undercuts or ridicules his narcissism — as Eyes Wide Shut did and as this movie does even more noticeably. Though given that Cruise produced this movie, I may be deluding myself in precisely the way he wants me to. Of course, not knowing who’s calling the shots or what’s real and what’s not is partly what this movie is about. So sorry, I can’t tell you whether you should go see Vanilla Sky. That depends on factors about you I can’t claim to know.