From The Soho News, March 4, 1981. — J.R.

Dixiana Moon

By William Price Fox

Viking Press, $11.95

Any kind of sales talk, no matter how witty or effervescent, eventually goes stale or rancid in your head — until it is replaced by a new slogan. This is what Dixiana Moon is all about, and, just as unavoidably, what it’s like: drifts of euphoria that gradually work their way up to nausea, peaking in a blissful forgetfulness that efficaciously clears the way for bright new ideas to come along. It is also what journalism — a quaint subcategory of advertising — is about and like, this review included: a laxative for the imagination intended to move goods as quickly as possible, straight through the digestive tract.

Dixiana Moon is a quick and agreeable read, no doubt about that. One way or another, the whole novel is about packaging. The narrator hero, young movie freak Joe Mahaffey, has a lovable dreamer of a father in rural Pennsylvania, who keeps repackaging a nightclub in different décor — French, Spanish, Irish, Italian, and so on — while Joe Jr., hoping to win the affection of Monica Murphy (an “executive dancer” whom he crosses profesional paths with in Manhattan’s Danceland), signs on as a salesman for a packaging outfits, and peddles polyethylene bags in diverse spots east of Pittsburgh. Eventually he runs into Buck Brody, a middle-aged Southern “mush-mouth” (I’d cast Ned Beatty) who quickly becomes a substitute father, yanking Joe into one outrageous get-rich scheme after another.

The culminating package takes shape in Georgia — a circus combined with a fundamentalist revival called The Great Mozingo-Arlo Waters Jubilee Crusade and Famous Life of Christ Show. Mozingo is merely one of Buck’s aliases, but Arlo Waters — a terrifying, noncomic portrait etched in grease and acid, a Hazel Motes without laughs — turns out to be the genuine article, a lunatic and fanatic who ushers in an apocalyptic climax. Like Joe Jr.’s triumphant arrival on the lion-flanked steps of the New York Public Library in Chapter 1, it is a public event described in terms of camera placement, this time TV coverage; and there’s a solid indication that it is media exposure that finally pushes Waters over the edge.

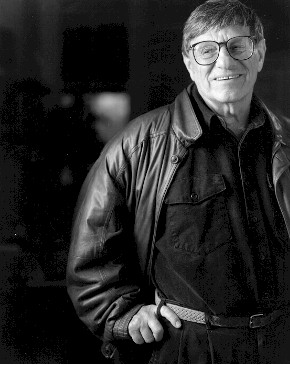

On the jacket blurb, Pauline Kael affectionately celebrates the novel’s Southern “boozing grunginess” — the sort of thing she sometimes swoons over in minor Peckinpah — and indeed, flashes of Fox’s talented gonzo patter actually suggest what a stream-of-consciousness novel by Kael or one of her disciples might be like: “It was probably beautiful up around Syracuse. The snow would be six feet deep and cut away like angel-food cake. In the north country they have sharp seasons. And the people match the seasons: they make sharp decisions. Down here nothing was straight. Everything was laid back and fuzzy. They’d grin and shuffle and ‘aw shit’ and ‘aw shucks’ you to the wall. No one would give you a straight answer on anything.”

This is charming travel-poster stuff, even to a Southern expatriate like me, that starts to lose conviction only when it becomes too serious, and loses interest only when it becomes too light. Its easy rhythms — which largely depend on matching phrases of roughly equal length — are heard more than seen, and felt more than thought. It’s white Southern jive, ad-copy style, in love with its own philistinism and body odor, and Fox writes it better than most.

Here’s part of an ad quoted in an earlier (and somewhat lesser) Fox novel, Ruby Red: “I want all you folks out there in radio land to know we’ve got us a policy down at Renfro Motors that no other car lot in the country can stand up to. We don’t have any bathing girls sashaying or brass bands or plastic doolollies spinning in the breeze. We don’t feature none of that nonsense. All we have is a simple, cold-biscuit down-to-earth policy of Truth. That’s it folks, capital T.R.U.T.H….”

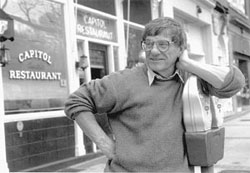

You said it. And even if this truth should break down when you’re driving it home, what the hell — we’re all supposed to be marks and losers anyway. The jacket flap on Ruby Red, published 10 years ago, wistfully reports that Fox has been bellhop, short-order cook, salesman, coach at a boys’ school, Air Force pilot, and lookout for a moonshiner — not to mention a teacher of creative writing in Iowa City. But as Dixiana Moon proves, right down to its own dreamy jacket and press kit, it’s the packaging that makes all the difference.

— The Soho News, March 4, 1981