From the May 26, 2000 Chicago Reader. I must confess that I’m embarrassed by most of my other reviews of Claire Denis films on this site. Writing from the Trumsoe International Film Festival in Norway, where I resaw many of her films at a retrospective, I discovered how they invariably seem to improve on repeated viewings. (I also reprinted this piece on Beau Travail in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition.)

Part of what’s both great and difficult about Denis’ films has been discussed perceptively by the late Robin Wood in one of his last great pieces, about I Can’t Sleep. And part of what I think is so remarkable about Claire, one of my favorite people, is a trait she shares with the late Sam Fuller, which might be described as the reverse of the cynicism of the jaundiced leftist who loves humanity but hates people. Fuller and Denis both show very dark, pessimistic, and even despairing views of humanity in their films, but their love of people and of life is no less constant. (Jim Jarmusch shows a bit of the same ambivalence in some of his edgier films, such as Dead Man, Ghost Dog, The Limits of Control, and Paterson.) —J.R.

Beau Travail

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Claire Denis

Written by Jean-Pol Fargeau and Denis With Denis Lavant, Michel Subor, Gregoire Colin, Richard Courcet, Nicolas Duvauchelle, Adiatou Massudi, and Bernardo Montet.

Maybe freedom begins with remorse. [Pause.] Maybe freedom begins with remorse. I heard that somewhere. —from the narration of Beau travail

I know it sounds fancy to say this, but the difference between Claire Denis’ early work and Beau travail, playing this week at the Music Box, is quite simply the difference between making movies and making cinema. By analogy, Charlie Parker went from playing jazz with Jay McShann to making music with his own groups, and that quantum leap included content and substance as well as technique — matter and manner became indistinguishable. Denis too has developed a new kind of mastery while tackling a new kind of material.

The predominant mode of this material is reverie — poetic rumination that pointedly doesn’t discriminate between major and minor events, intertwining both into a kind of endless magical tapestry. A gorgeous early image superimposing emerald blue water in motion over a hand writing in a diary evokes the magic to come. At times the movie suggests Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line without the warfare; Denis works in a wonderfully spare and beautiful style that allows mountains, plains, deserts, and bodies of water to speak eloquently for themselves, and she lets a tone of plaintive lament in the offscreen narration run across these diverse settings and textures without ever becoming self-pitying. (Literally, “beau travail” means “beautiful work,” and idiomatically, it might be translated as “good work” or “fine craftsmanship”; all three meanings are apt.)

In interfacing everyday banality with tragedy and violence, the film bears an indirect relationship to two important French New Wave features of the early 60s, Jean-Luc Godard’s Le petit soldat and Alain Resnais’ Muriel, both of which dealt with the contemporary — and then-taboo — subject of the Algerian war. (Initially the Godard film was banned in France and the Resnais film widely attacked; both were commercial flops just about everywhere they were shown.) In different ways, both of these controversial and courageous films examined the impossibility of dealing with torture and violence in Algeria in relation to daily life in Europe at the time; Beau travail — set in contemporary Marseilles and peacetime Djibouti, where an interracial group of legionnaires is camped — is explicitly postcolonial. (It alludes specifically to Godard’s film by casting that film’s lead actor, Michel Subor, as a character with the same name, Bruno Forestier; the relation to Muriel is more tenuous, seen in the mood of lonely reflection and regret.)

Beau travail uses these New Wave touchstones in much the same way it uses Herman Melville’s Billy Budd and two of his late poems, passages from Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, and Djibouti itself: they’re not so much works to be adapted or sites to be explored as they are personal talismans, aesthetic aphrodisiacs, inspirational reference points, incantations. Significantly, Le petit soldat made similar use of some of its art references, though that made its political positions somewhat dandyish: Forestier was modeled after Michael O’Hara, the hero of Orson Welles’s The Lady From Shanghai, and his torture at the hands of the Algerian National Liberation Front was based on an episode in Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key. His narration in the film begins, “For me, the time of action is over. I’ve grown older. The time for reflection has begun.” And it ends, “I was happy, because I had a lot of time ahead of me.” The offscreen narration of Beau travail — spoken by Chief Master Sergeant Galoup (Denis Lavant) — begins, “Marseilles, late February. I have a lot of time ahead of me.” The difference between the Algerian war in the 50s and 60s and the relatively aimless futility of the Foreign Legion today may make the implied link seem anomalous. But other details support it: for example, Forestier in Le petit soldat was a French army deserter, and Denis’ Foreign Legionnaires are figurative or literal orphans — Galoup being the most painfully romantic loner of them all, styling himself as the perfect legionnaire, which reminds one of Melville as well as Godard.

The eldest daughter of a French civil servant, Denis spent nearly all of her preteen years in Africa, including Djibouti, and part of what’s so striking about her tale of the French Foreign Legion is that most of it doesn’t proceed like a tale at all. It grew out of a French TV commission to explore the theme of “foreignness,” and central to what makes it different from her earlier works is that she hired a choreographer, Bernardo Montet (who also plays one of the legionnaires), to help her stage some of the training exercises and maneuvers, which at times register like luminous and mysterious rituals. These are among the most alive and electric moments in the film — moments that improve on comparable passages in Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket and at times even recall certain exalted passages in Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky when the sweep of sculptural male torsos in formation perfectly matches the ecstatic cadences of Prokofiev’s music. It’s also central to Denis’ achievement that, with or without the astute musical choices — which also include a song by Neil Young, Afro-pop, Corona’s “Rhythm of the Night,” and legionnaire songs — one can’t always tell which of the scenes Montet worked on. The whole film unfolds like a continuous dance, and there’s as much choreography in the movements between shots as there is in the movements of the actors or the placement of the landscapes. (The notion of a military theater has seldom been so pronounced, even if it usually registers as avant-garde theater; how much this inflects the postcolonial meaning of the story, which pivots around the idea of existential futility, is one of the film’s key ambiguities.)

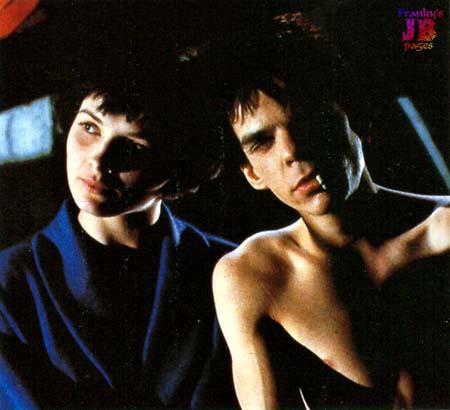

Lavant, the lead actor, is familiar to American audiences from his lead performances in the first three features of Leos Carax — Boy Meets Girl (1984), Bad Blood (1986), and Lovers on the Bridge (1992) — in which he plays essentially the same character, a guy named Alex, Carax’s own real first name. Trained as an acrobat and used like an actor in silent cinema for his sheer physicality, Lavant is almost a decade older than he was in Lovers on the Bridge, but he still seems like a switchblade ready to spring open. His contained intensity cuts loose in a solitary disco dance he performs at the end of Beau travail, in which he moves to “Rhythm of the Night” like a dervish, recalling one of his manic cadenzas in Bad Blood. His identity as Galoup is a far cry from his previous incarnations as Alex, yet Denis is clearly superimposing Galoup on Alex, just as she’s superimposing Subor’s Forestier on his Forestier in Godard’s film; Gregoire Colin’s Gilles Sentain might also remind one of his previous roles in Oliver Oliver, Queen Margot, Before the Rain, Denis’ Nenette and Boni, and The Dreamlife of Angels. All three of these characters are also designed to echo, respectively, Master-at-Arms Claggart, Captain Vere, and Billy Budd in Melville’s novella.

The plot, also suggested by the novella, consists of Galoup, alone in Marseilles and toying with the possibility of suicide, recalling his life in Djibouti before he was dishonorably discharged by Forestier, and selected memories of what led to his dismissal: developing an irrational and obsessive hatred for Sentain, a new recruit everyone else liked, and eventually dropping him off a truck in the middle of a desert with a faulty compass. Sentain almost dies but is found by African civilians and nursed back to health by a woman we see with him on a bus; the final glimpses we have of him are practically the only scenes that don’t include Galoup, and for all we know, they could be transpiring in Galoup’s imagination.

None of this is meant to imply that you need to have Denis’ cinematic, literary, or musical background to appreciate this movie. No more necessary are the two late Melville poems she cites as direct inspirations, “The Night March” and “Gold in the Mountain,” which suggest that raw feelings are what really count, not intellectual associations. The first poem reads:

With banners furled, and clarions mute,

An army passes in the night,

And beaming spears and helms salute,

The dark with bright.

In silence deep the legions stream,

With open ranks, in order true;

Over boundless plains they stream and gleam–

No chief in view!

The second reads:

Gold in the mountain

And gold in the glen

And greed in the heart

Heaven having no part

And unsatisfied men.

Machismo isn’t what I generally go to movies hoping to find, nor is the homoeroticism of military imagery. I suspect it was my lack of taste for the macho in general and Denis’ dark vision in particular that led me to write of her semiautobiographical Chocolat (1988) when it came out, “As a first feature, this is respectable enough work, though the intelligence here seems at times closer to Louis Malle (for better and for worse) than to any of Denis’ former employers” — i.e., Eduardo de Gregorio, Jim Jarmusch, Dusan Makavejev, Jacques Rivette, and Wim Wenders, all of whom she’d worked for as an assistant director. Since I didn’t like Malle as much as the other five directors — I thought his pessimistic view of humanity bordered on sadism — I suppose I meant mainly “for worse.”

The same bias also led me to choose adjectives such as “grim,” “sordid,” and “depressing” two years later when I reviewed Denis’ No Fear, No Die, a well-acted, noirish B-film about cockfighters in the Paris suburbs. And even though I liked her extended documentary Jacques Rivette, le veilleur (1990) and found more and more things to like in I Can’t Sleep (1994) and Nenette and Boni (1996), the most I could say for her until recently was that she was a talented filmmaker who didn’t speak to me. I Can’t Sleep, a serial-killer movie, offered an interesting portrait of a Paris neighborhood, but it seemed to wallow in a kind of professional morbidity; Nenette and Boni, an even more troubling — and more interesting — sicko story about two teenage siblings in Marseilles, irritated me by coyly suggesting incestual abuse without being explicit.

Did previous Denis films have a poetry I didn’t notice or appreciate, or did she make a quantum leap as an artist in Beau travail? Probably some of both. In any case, I now think she’s capable of poetry well beyond the range of someone like Malle. And it isn’t as if the homoeroticism here makes her a soul sister to Jean Genet, even if some of her imagery — perhaps most notably a patch of lyricism about legionnaires ironing trouser creases — calls him to mind. In fact, “homoerotic” might superficially describe a few strains of the polytonality Denis is working with (Kent Jones aptly cites Ornette Coleman in the May-June Film Comment), but it isn’t an adequate label for her new material.

Part of what fascinates me so much about Beau travail is how unmistakably it qualifies as a film directed and cowritten by a woman (and, incidentally, shot by another woman, Agnes Godard), even though it doesn’t conform to any platitudes about women filmmakers’ films. For instance, I can’t for the life of me think of another film by a woman that reminds me of Eisenstein. Beau travail evokes him not only in the aforementioned encounters between sculptural bodies and heroic music, but in its musically inflected montages and its beautifully ordered compositions devoted to various maneuvers: crawling under barbed wire, vaulting over bars, occupying the shell of a half-constructed building, walking across parallel wires like tightrope artists imitating flurries of notes on a musical staff. (Leni Riefenstahl gave us only kitsch Eisenstein at best, and she was much more conventionally homoerotic in both Triumph of the Will and Olympia.)

Maybe what most marks Beau travail as a film by a woman is the way Denis uses African women to subtly impose an ironic frame around the story; from beginning to end, they figure implicitly and unobtrusively as a kind of mainly mute Greek chorus — whether they’re dancing in the disco, speaking in the market, appearing briefly as the girlfriends of some legionnaires (including Galoup), or serving as witnesses to portions of the action. They’re clearly outside the plot, yet they’re by no means absent, either physically or morally — and their noble function is underscored by the contrast between the splashy colors of their apparel and the green rot of the military uniforms. In an early scene, when the women briefly observe the meaningless occupation of the construction site and begin laughing, the choral function of the perpetually amused black characters in Elia Kazan and Tennessee Williams’s Baby Doll is what sprang to my mind. The film virtually opens with women dancing to Afro-pop in the same disco lounge where Galoup explodes at the end, punctuating the tune they’re dancing to with what Stuart Klawans in the Nation calls air kisses. These playful, pecking riffs, which are like little laughs as well as kisses, mock the very notion of a mating ritual, which in effect means mocking in advance Galoup’s melodramatic-romantic obsession with Sentain and all the turmoil it produces. And implicitly they mock his doomed and equally absurd love affair with the French Foreign Legion.