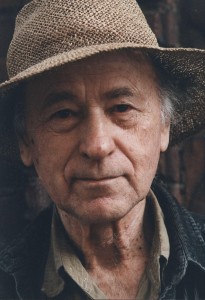

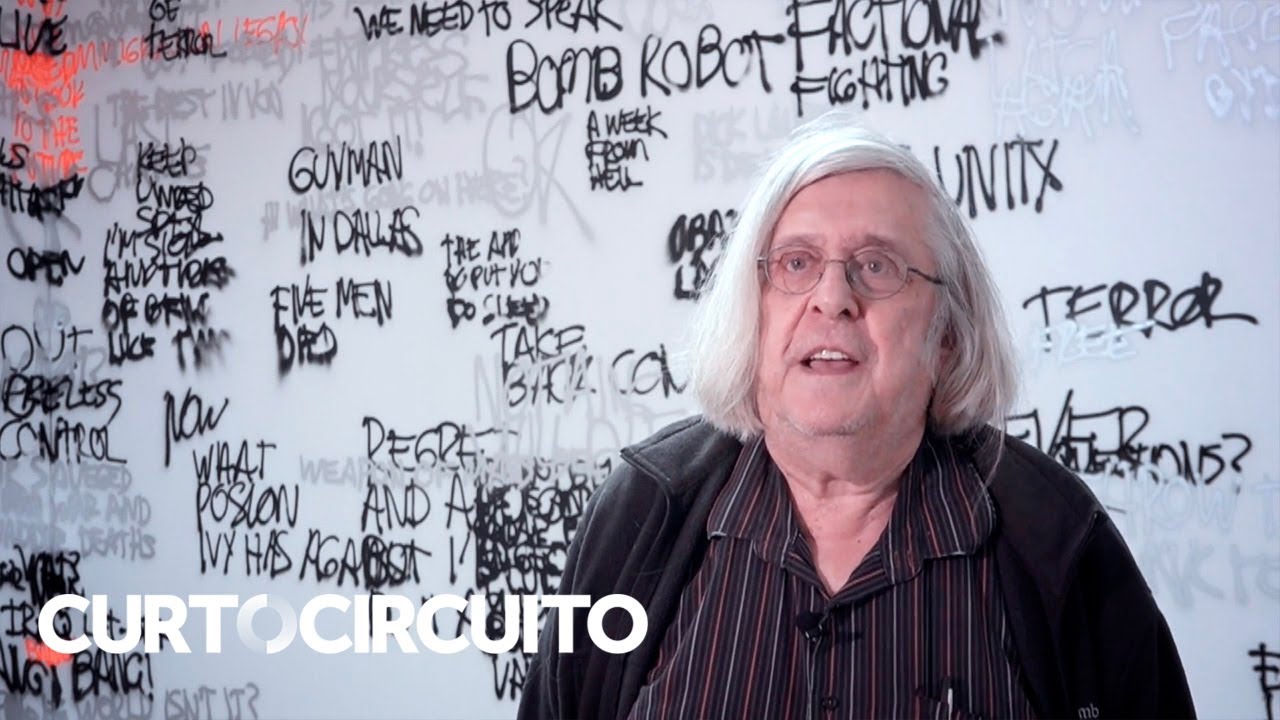

The following interview by Sara Donoso, printed in Spanish and English in Fotocinema no. 14 (2017), was conducted in Santiago de Compostela while I was serving on the jury of Curtocircuíto, the international festival of short films held there. I’ve taken the liberty of lightly revising Donoso’s English, and I’ve also retained her Spanish introduction.– J.R.

THE EXPANSION OF CRITICISM: AN INTERVIEW WITH JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

Sara Donoso

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, España

saradonosocalvo@gmail.com

Crítico, ensayista y teórico de cine, la pluma de Jonathan Rosenbaum es de aquellas que practican el ejercicio de la resistencia; que se oponen a la clasificación, las etiquetas, al mundo del mainstream y a la cultura del espectáculo. Podríamos decir que es uno de esos críticos tal vez incómodos para algunos pero necesarios y reveladores para quienes aprecian el séptimo arte. Tras trabajar como principal crítico del Chicago Reader entre 1987 y 2008, actualmente sigue ejerciendo el ejercicio de la escritura cinematográfica a través de su página web, en la que no solo postea periódicamente reseñas de libros o películas sino que cuenta además con un archivo de publicaciones anteriores.

Como autor y editor, ha contribuido a través de diferentes proyectos a la difusión y dignificación del cine más allá de los circuitos comerciales, siendo responsable de títulos como Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003),Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) o Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (2010).

Su participación en Curtocircuíto. Festival Internacional de Cine de Santiago de Compostela, me dio la oportunidad de aproximarme a sus modos de analizar el cine, de repensarlo casi como extensión de la vida. Conversamos sobre las filias y las fobias de la crítica, sobre el binomio cine/arte y los retos a los que se enfrenta el cine en la actualidad.

Your love for literature and your desire to become a writer eventually led to a professional job as a film critic. Is there creative freedom in this kind of writing, too?

I’ve been a writer much longer than I‘ve been a film critic. I knew I was a writer when I was in grammar school. When I was very young I wrote a lot of stories and poems, and when I was a teenager I wrote a novel. I rewrote that novel in my 20s and then wrote another. I grew up seeing a lot of films because my family ran a small chain of cinemas in Alabama. My attitude about cinema, in a way, is that cinema is literature by another means.

You have stated that your job is not to judge films, but to encourage discussion about them. Is it common to confuse specialized journalism with film criticism?

I think that there is a big difference between being a reviewer and being a critic. Because being a reviewer means sort of like telling people what films they should see, and the difficulty of doing that is that the same films aren’t good for everyone. When you say a film is good you have to say good for whom and for what. You can’t just say a film is good by itself because this doesn’t mean anything, at least for me. That is why I think it is very important to not try to be definitive about anything, but to explore and to extend a discussion.

Alongside the critic’s opinion there is usually a rating from 0 to 10. This is something that happens in both traditional media and online platforms. What do you think about it?

Yes, when I was at the Chicago Reader I had to give, not from zero to ten, but one, two, three, or four stars when I wrote long reviews. That was required and it can be important in a polemical way to say you like something very much. At the same time, my opinions about certain films change when I see them again; sometimes they get better, sometimes they get less interesting. In this sense, I think that giving stars and ratings is done for the market, but it isn’t done so much for the public in the same way. It oversimplifies. It’s easier for me if I don’t have to do that.

This tends to tilt the balance in favor of one film over another.

Well, one does make comparisons, but I think that it’s probably more appropriate to make comparisons between other films by the same filmmaker or other films on the same subject, things of that kind. Part of the problem is that, over time, values change…The world we live in changes, and because the world changes, how we value films changes also. If you compare films, it is very important to say “at this moment, now, I prefer this film to that film”, but next week it may be different.

I would like to discuss with you the following quote by Jonas Mekas: “…the works of art, the works that help to stir man’s vision, man’s imagination, man’s mysteries should be brought to our attention (…) Our movie reviewers, the press, radio, TV, our movie critics have become part of a middle-aged conspiracy that keeps all the doors locked” (“The Diary Film,” 1965). In light of this, where would you say we are nowadays?

I think that Jonas is partly right in the sense that most of the discourse about film is controlled by the industry, like Academy Awards for example. Usually most of the industry is interested in convincing people that only about five films are important each week and that everything else doesn´t matter, but nobody is in a position to know that because there are too many films, and nobody sees everything. It is a very poisonous attitude but it’s one that rules most criticism and reviewing, unfortunately. Sometimes, when I worked as a reviewer for the Chicago Reader, people would say, “Why are you writing about films that I have never heard of ?” I think that what they really meant was “Why are you writing about films that don´t have multimillion-dollar ad campaigns?”

Because those are the films they hear about. I think that it becomes more of the job for reviewers who are interested in a wide view of cinema to talk about the films, to advertise the films that don´t have advertisements.

A great part of the film industry is being absorbed by the Hollywood establishment. This has resulted in the production of films that seem to be copies of one another. On the other hand, independent filmmaking seems to be isolated. This always makes me wonder: is this due to audience’s taste on films, or is it linked to market interests?

I think the problem in this case is that most people don’t really know what they want to see, because what they know is based on what they hear about and what they hear about is based on advertising. Escaping from marketing interests is very important, but it isn’t easy.

Is the Internet beneficial for this kind of cinema?

One of the advantages for people who like to explore the Internet is to make discoveries and to go beyond the usual things that they hear about, but some people only like to stick to the same things. The Internet can now be much more specialized and focused, and people who already have an interest in a particular kind of cinema, that it is more marginal, can actually look and find out about those films. It also creates a situation of people who keep downloading things, even though they don’t know what they’re looking for. If they don’t know what they’re looking for, they wind up seeing the duplication of what’s in the mainstream. I think that the Internet makes things better in some circumstances, and makes things worse in other circumstances. It all depends on how the readers are oriented before they read anything.

You have always kept your work far from mainstream cinema in order to increase the visibility of less conventional cinema. What effect has this had on your readers?

I think I was closer to writing for the mainstream at certain times, for example when I wrote for the Chicago Reader. Even though it wasn’t the same as a big newspaper, I still wrote for many more people than I write for now, about a hundred and thirty thousand circulation, which is large. The question is: Would you like to influence a few number of people a lot or a lot of people a little? I prefer to affect a few people a lot because I think that actually has more intensity and it is more satisfying, but many of my colleagues prefer to reach a lot of people, even if they don’t communicate as much.

The lack of women filmmakers is surprising. In your long career, have you been able to identify the reasons behind this?

I think it has a lot to do with power and plus the fact that most of the world is sexist. I actually don’t feel that there is a lack of woman filmmakers, there is a lack of attention given to woman filmmakers. I know a lot of woman filmmakers and I think they are all very important. This has been true for much of the history of cinema, but we were not aware. Also women were sometimes very important behind the scenes and they often got important positions, but they often got marginalized. For example, Alfred Hitchcock’s wife Alma was very instrumental and influenced all of his films and he often got her advice. So, I think that there is a kind of way in which the power relations in the world of cinema reproduce the power relations in the larger world, and that tends to marginalize the work of women. That is why even, for example, in the presidential election you could have Donald Trump saying something ridiculous like “Hillary Clinton lacks stamina”, when all he is really saying is “she is a woman”.

Promotion and dissemination are challenging issues for today’s independent cinema. What can be done to encourage the audience’s interest in non-conventional films?

How to awake the public interest? I think that depends on interest in what. Sometimes the subjects of films are very important and that can get people interested. But the USA is very perverted because there are certain political and historical issues, social issues, that are not discussed unless there is a trauma about it, and then everybody discusses it, all of a sudden. For example, before Oliver Stone made JFK about Kennedy´s assassination, there were lots of things in the news about who really shot Kennedy that were considered illegitimate. Suddenly, when there was a movie, it was on the front page of the New York Times and it was OK to talk about the same issues. That is really showing the power of the big companies and the advertisers. We can’t say that this is about the taste or the interest of the public because the public can only know about what it sees. Reminds me of the joke about a place that sells orange juice in Florida that offers “All the orange juice you can drink for a dollar” and then they give you a tiny little glass and they say “That´s all the orange juice you can drink for a dollar”.

I think that is the trouble, I mean, people don’t know what the choices are. It’s not like they are going to the cinema and saying “I’m choosing to see a James Bond film rather than an Abbas Kiarostami film” because they have never heard about Abbas Kiarostami, so they don’t know that they’re making a choice. There’s a lot of mystification about all of that.

It seems to me that critics usually find symbols and references related with the work they are analyzing everywhere. Creators, on the other hand, are not happy about this. As a film critic, how do you deal with this?

In terms of influences and references, I have a weakness for probably talking about this too much. Well, if people know the references obviously it helps a lot, if they don’t know the references then you are writing for a smaller group of people, which sometimes is the case with me. Influence is a little tricky because I think that one of the problems in writing any kind of criticism is artistic intentions. We don’t know anything about intentions and, if we pretend that we do, we are often being false because even the artist who claims that he or she knows the intentions of the work doesn´t mean that that´s necessarily accurate about what the intentions are. Also the intentions are very different from the effects and the consequences. So, it´s not fruitful to talk about intentions. Part of what critics do is to place the works in a particular context. In order to do that, you obviously need certain references and sometimes speaking about influences can help in that as well.

There is this division between “market-oriented” cinema, and artistic, poetic (usually independent) cinema, which, I think, is closer to art. How do you identify this, let’s say, poetic and artistic universe; where do you place the border between art and market?

The interesting thing is that there are sometimes different reasons for liking the same films and sometimes they correspond to how the film is marketed, but at other times they don’t. Sometimes the real interest of a film is different from the way it’s described by the marketing; a commercial film might be poetic but it may not be advertised that way. I think that’s partly why the role of the critic becomes important: intervening and sort of saying, “The ads are not exactly right, they’re misleading, and sometimes it’s important to see other things”. A lot of films that I show in my courses are basically films that do not really fit in marketing categories. In that sense, a critic is always competing with the marketplace, because they are trying to give labels to things, and it is just a question about how useful they are. And useful to whom? Is it useful in selling the film? Is it useful in helping you appreciate the film if you’ve seen it? It could be useful in different ways and I think that there is very often a confusion between these categories. My favorite American film critic of all is a film critic who is not well known outside of the U.S.: Manny Farber. One thing that was unusual about him was that he was never used in ads, because of his writing style. You couldn’t even tell whether he liked the film or not. The fact that he couldn’t be used in advertising was a disadvantage as far as the marketplace was concerned. And he was less popular as a reviewer for that reason.

Do art criticism and film criticism share a common space?

I think there is a big difference between the art world and the cinema world, partly because of the different ways the marketplace works in each case. Also, at least in the United States, people who are wealthier, have more money and collect art and so on, are a separate group. Also, the ways in which art is shared in both movie theaters and in museum are very different. Even though they are both open to the public, you aren’t usually sitting with the same people who are walking through an art gallery, you aren’t sharing space in the same way with other people. The fact that we watch films on the dark also makes it different. There are a lot of differences certainly in terms of public dissemination. It’s also true that they are both very much dependent on journalism and advertising and things like that, but they move in different circles.

A lot of films explore forms and compositions that get away from narrative structures. Many of them are halfway between cinema and video art. However, it is really difficult to watch these films outside of specialized festivals. They are not available for the general public at regular movie theaters, museums, etc. Should art institutions support this kind of cinema, or is this a job that should remain a responsibility of the film industry?

Well, I don’t know. It seems to me that art institutions should redefine whatever they’re doing in order to make their own works, the ones they are showing, more accessible. I don’t see it as being the responsibility of one or the other. Or maybe it is the responsibility of both, but I think both should expand their options in order to circumscribe their own public.

If we think about filmmakers such as Sharon Lockhart or Chris Marker we know that their work is moving in a thin line between art and cinema. I think this is something that we should take into account because it concerns a lot of filmmakers.

I am not nearly as well versed in gallery art, in installations and things like that, which concern a lot filmmakers. At the same time, when you think about the history of cinema, when it started out it was in things that were very much like exhibition spaces but not in cinemas. So, in a certain way, there has always been this kind of transformation. The fact that people are watching films at home now also makes a lot of changes. It was interesting to me, for example, when Abbas Kiarostami made a group of films called Five. He would show them at galleries but I found it a very bad experience watching them that way, whereas, if you watched it at home, it was kind of like listening to chamber music and you needed quiet, no distractions and no other people around… I think that is one of the issues that arises. Each work places different demands on us and there are different ways you can argue about the most advantageous way to look at the work. Sometimes it does correspond to the spaces that are available to us when we look at them. It is important to try to make those distinctions. For example, if you are showing something in a gallery, it’s important to decide whether it’s useful to have a room that is dark to watch films in or, if it’s bright, to explain if you should be sitting or you should be standing. I think these are all important things and people don’t often think about them at all. It’s all about the atmosphere and the social context.

Who, in your opinion, should write about this kind of films? Art critics or film critics? Do you think that hybrid analyses are possible?

I actually think that sometimes it is very refreshing for people who are not specialized in cinema to write about films. Because part of the problem is that even people who are considered professionals don’t always deserve to be called professionals. The reasons why people are hired to write for newspapers, certainly in the United States, usually have little to do with how much they know about film. Sometimes the less they know the more likely they are to get the job, because they want people who don’t intimidate the public, so they feel like that they know more. I am very suspicious of the whole idea of professionalism and expertise that applies to academic criticism also, because I think a lot of people who have PhDs don’t know anything about films, whereas people who have no degrees sometimes know a lot. It very much depends on individual cases.

In fact, the analyses that are part of Movie Mutations suggest a new way to think about cinema, a way that is different from that of academic essays (that have to comply with very strict rules), and which is, at the same time, devoid of journalistic superficiality.

It’s interesting that you think the analyses in Movie Mutations are different, so I’m curious to ask you…different in what way? When you say different from academic essays because of the rules, I think criticism deals with all kind of rules, but sometimes the rules are different.

At least here in Spain, the academic tradition has imposed a very strict set of rules that dictate how to write and how to approach the subjects you discuss. Academic writing has a rather closed structure.

I never got a PhD, I studied literature, but I only did a master’s thesis. I never ever wanted to try to publish it because the form of that was so repugnant to me. I think there is a difference between academic writing and journalism. There is good academic writing and good journalistic writing but, I think, often the rules in journalistic criticism are like a straitjacket. What I like to do as a writer in journalism is to explore subjects. I often don’t know what I think about something until I write about it, and I write about it in order to know what I think about it. But it’s hard to do this academically. In a certain way, the problem with academic writing is that you already know what you want to say, so in a way there is no reason to write it. If whatever you write as an academic has to be boring, your job becomes boring by definition and by necessity.

What are, in your opinion, the main aesthetical and conceptual changes that have taken place in cinema in the last few years? What are the main challenges that cinema has to deal with nowadays?

One of the changes is in taste, which is different from aesthetic and conceptual changes. But it seems to me that young people are much more sympathetic to difficult films than they used to be, which is a very good sign. There are more interesting difficult films now than there were in the sixties, for example. One thing that it is obviously a change in aesthetic and conceptual decisions is this whole kind of confusion between what is cinema and what is video. The experience of the film or video to me is based on how you see it, and people don’t often talk about those things. I think this is something that has complicated the whole position of criticism. On the other hand, there is another important thing about the fact that many more works have become available because of the Internet, and DVDs, etc. Criticism is different, too. When I was in college, I would see a film and it would have a big effect on me and I would wait two or three months before I met someone else who saw the film and before I read about it in a magazine. Now, I can see something really interesting and immediately read about it on the Internet. I think there’s an important difference in that, which actually helps communication and creates a new kind of community. What I also find interesting is that it’s a more natural growth. One of the advantages is that people aren’t paid to be film critics now so much. A lot of people think that this is a disaster, but you could argue that it’s good, because, if people really care about film and writing about film, it’s because they care about it and not because they expect to be paid for it. So, in a way, it purifies professional criticism.