From the Chicago Reader (July 13, 2001). — J.R.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Written by Spielberg and Ian Watson

With Haley Joel Osment, Jude Law, Frances O’Connor, Brendan Gleeson, William Hurt, Jake Thomas, and the voices of Jack Angel, Ben Kingsley, Meryl Streep, Robin Williams, and Chris Rock.

If the best movies are often those that change the rules, Steven Spielberg’s sincere, cockeyed, serious, and sometimes masterful realization of Stanley Kubrick’s ambitious late project deserves to be a contender. All of Kubrick’s best films fall into one vexing category — they’re strange, semi-identified objects that we’re never quite prepared for. They’re also the precise opposite of Spielberg’s films, which ooze cozy familiarity before we’ve figured out what they are or what they’re doing to us. If A.I. Artificial Intelligence — a film whose split personality is apparent even in its two-part title — is as much a Kubrick movie as a Spielberg one, this is in large part because it defamiliarizes Spielberg, makes him strange. Yet it also defamiliarizes Kubrick, with equally ambiguous results — making his unfamiliarity familiar. Both filmmakers should be credited for the results — Kubrick for proposing that Spielberg direct the project and Spielberg for doing his utmost to respect Kubrick’s intentions while making it a profoundly personal work.

I can’t agree with colleagues who label A.I. a failure because it’s neither fish nor fowl — by which they usually mean a failed Spielberg movie, not a successful or even semi-successful Kubrick one. Neither fish nor fowl strikes me as precisely what a good SF movie should be — it’s certainly what 2001: A Space Odyssey was when it opened in 1968 before puzzled viewers, myself included. Of course 2001 qualifies as a stranger-than-usual Kubrick film, so perhaps it belongs in a different category altogether.

David Denby writes in the New Yorker, “Whatever is wrong with A.I. — and a great deal is wrong — it’s the first American movie of the year made by an artist.” He’s not only trashing the work of hundreds of filmmakers whose work he hasn’t seen — which must come from yearning for a world much simpler than our own, a yearning Spielberg generally speaks to — but is also making it clear that he has only one artist in mind, and it isn’t Kubrick. Denby treated Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick’s final film, with the kind of dismissive contempt that would have seemed excessive if it had been ladled on a James Bond feature, and I can only surmise that for him, Kubrick doesn’t even qualify as a bad artist, alive or dead. So Denby must have been hoping for another Spielberg film, much as I was hoping — even less realistically — for another Kubrick. But only if you accept that A.I. can satisfy neither expectation will you understand the film’s special achievements, which include redefining and expanding our sense of both filmmakers.

I find A.I. so fascinating, affecting, and provocative that I don’t much care whether it’s a masterpiece or not — a verdict that won’t be determined for months or years anyway and that would be useful right now mainly to exhibitors and DreamWorks executives. The example of both filmmakers’ previous works and their often hysterical receptions should have taught us the folly of hasty evaluations. How many people are still calling 2001 “stupid” and “a celebration of cop-out,” as Pauline Kael did, or Saving Private Ryan the film “to end all wars,” as the New Yorker trumpeted on a cover wraparound? Calling a movie a masterpiece is in some cases little more than an impatient desire to close off discussion of its ambiguities and uncertainties, to deny that it’s a living, and therefore evolving, work of art. A.I., which often resembles two slightly distorting mirrors facing each other, is likely to unsettle and confound us for some time to come — and that’s entirely to its credit.

Unlike Denby, I don’t think that Spielberg’s being an artist places him in some special category, and the flag-waving hypocrisy of Saving Private Ryan is one of the examples I could cite as a dubious use of his artistry. Given the different kinds of art they’ve made, I also wonder whether it’s possible to reconcile the values of a “successful” Spielberg with those of a “successful” Kubrick in the same film. A.I. is, unavoidably, something of a shotgun marriage, though that’s what allows it to defamiliarize Kubrick and Spielberg — and the usual meaning of four stars. A.I. is one of the most poetic and haunting allegories about the cinema that I can think of, and whoever made it possible deserves to be roundly applauded. It’s also the most philosophical film in Kubrick’s canon, the most intelligent in Spielberg’s, and quite possibly the film with the most contemporary relevance that either one has made since Kubrick released Dr. Strangelove in 1964.

People who remain baffled that Kubrick ever proposed that Spielberg direct A.I. are perhaps succumbing to media typecasting of both filmmakers. (Kubrick also considered directing and having Spielberg produce.) The two did have things in common — they were both middle-class Jewish prodigies and technical wizards who leaned toward war movies, SF, and adolescent sexuality and humor. But there were also practical reasons why Kubrick — who met Spielberg in 1979 in London, where he was doing preproduction work on The Shining and Spielberg was doing the same on Raiders of the Lost Ark — thought of turning to him. After Kubrick explored in vain the eerie idea of creating an actual robot to play the lead part and perhaps of creating a digital performance, he recognized that his insistence on long shooting periods might make the aging of a child actor visible. Spielberg’s speed on a soundstage and his masterful ability to quickly create a clear narrative — he reportedly shot A.I. in three and a half months, the same length of time it took him to write the screenplay — eliminated that danger. (Kubrick also thought that Spielberg could handle sentimental material better than he could.)

Once Kubrick’s brother-in-law and widow persuaded Spielberg to take on the project, believing he was the only one who had the right, he apparently did his best to honor Ian Watson’s 90-page script treatment and Chris Baker’s 600 drawings, both created under Kubrick’s close supervision. Yet he also adapted the material to his own taste and inclinations, which seems the only logical way he could have proceeded. Reportedly, the most important changes made were in the story’s middle section, which Kubrick had been dissatisfied with, where the robot character Gigolo Joe was a more twisted and less comic figure; by his own admission, Spielberg made him into something like a scoutmaster, and one wonders if the iconographic allusions to John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever, another relatively innocent figure, are also his. Some reviewers seem happier with this character than with anything else in the film, but I’d argue that he stands at the furthest remove from the film’s philosophical inquiry, apart from his chilling parting line: “I am…I was.” As a character and as a robot he’s obviously built to please, but he seems to carry off the former role more convincingly. (Spielberg backs away from showing him pleasing his clients in any detail.)

I hope that the film’s major sources — Watson’s treatment, Baker’s drawings, and Spielberg’s screenplay and designs (also done with Baker) — will eventually be made available; the drawings alone, or at least a selection, might make a swell DVD bonus. (Brian Aldiss’s source story, “Super-toys Last All Summer Long,” is readily available.) These materials are far from exhaustive, because the project went through a gestation as complex as that of Eyes Wide Shut; Kubrick contacted at least four other writers to develop it at various stages — Aldiss, Arthur C. Clarke, Bob Shaw, and Sara Maitland — and there may well have been more. (Maitland, interviewed in a documentary made shortly after Kubrick’s death, was brought in after Watson; she quotes Kubrick telling her, “I need someone to smear this with vaginal gel.”) Perhaps much of this work was abortive, but it would be helpful to have at least the main outlines. And until the Watson and Spielberg scripts surface, any guesses, including mine, about which aspects of the film can be credited to which director are bound to be somewhat haphazard. (I’m about to give away the plot, so readers who haven’t yet seen the film might want to check out here.)

In a future where the greenhouse effect has melted the polar ice caps, flooding the earth’s major cities and displacing millions of people, robots — or “mechas,” as they’re called here, in contrast to “orgas,” meaning us organic folk — become more prominent, leading humans to fear that robots will outlive the human race. (This is what happens; “They made us too smart, too soon, and too many,” says one robot.) A scientist named Professor Hobby (William Hurt) proposes building a robot that can love not other robots — a possibility the film chooses not to explore, except indirectly — but human beings. This raises a moral question broached in the film’s opening scene: what responsibility would humans have regarding such a creation? The implicit answer: about the same responsibility George W. Bush seems ready to take for curbing the greenhouse effect.

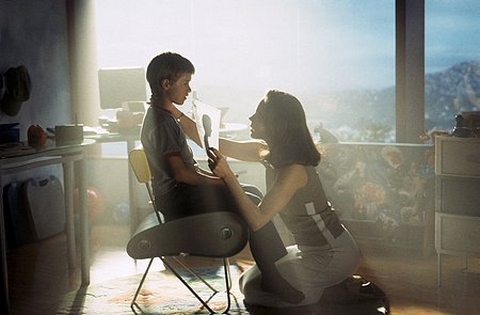

Hobby’s creation turns out to be a boy named David (Haley Joel Osment) who’s sold to Monica and Henry (Frances O’Connor and Sam Robards), a traumatized couple whose natural son, Martin (Jake Thomas), is in a coma. (One of countless Kubrickian references that surely wouldn’t have been part of the film if Kubrick had directed it, Martin’s kept in a see-through deep-freeze coffin recalling the hibernation berths of the astronauts in 2001.) Warned that once he and Monica program David to love someone in particular they can’t reverse their decision, Henry brings David home to Monica, who’s initially horrified by the notion of anyone substituting for Martin and seems perturbed by such traits as David’s inability to eat or sleep. But she slowly warms to the idea of an artificial son, at least as a concept, and when she eventually programs him to love her she recites her own name twice as part of the imprinting process, but not Henry’s. The first sign that David has changed is when he calls her Mommy instead of Monica.

Things start to unravel once Martin miraculously gets better and returns to the couple’s suburban home, raising the specter of sibling rivalry. After David displays some aberrant forms of behavior in response to cruelties by humans — including cutting off a lock of Monica’s hair at Martin’s instigation and almost drowning Martin at his seventh-birthday party — Monica tearfully abandons him with his “super-toy” Teddy, a teddy bear, in the middle of a forest.

David is persuaded by the story of Pinocchio that Monica will love him if he becomes a real boy, and that goal becomes his obsession. He has various adventures with Gigolo Joe (Jude Law), another fugitive — barely escaping a Flesh Fair, where robots are brutally destroyed for the delectation of angry humans, and visiting Rouge City to consult a computerized oracle named Dr. Know. From there he’s led via a quote from William Butler Yeats’s “The Stolen Child” back to Professor Hobby in the remnants of Manhattan, where David discovers to his horror (and Hobby’s delight) that he’s merely a prototype, a “successful” experiment. Attempting two different forms of suicide — first by brutally destroying one of his many doubles (an especially creepy scene), then by falling from a skyscraper to the bottom of the ocean — he winds up inside a helicopter boat with Teddy, gazing at Pinocchio’s Blue Fairy in the underwater ruins of Coney Island and pleading with her to make him a real boy.

Two thousand years pass, during which human life perishes but David remains firmly fixed on the Blue Fairy, who resembles Monica. He’s discovered by future beings that resemble the aliens in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (except that they appear either to combine the categories orga and mecha or make them both irrelevant), who transmit his life story to one another through movielike pictures.

Working from these projections, which re-create the suburban home where David once lived, and using the lock of Monica’s hair that Teddy has preserved, they explain to David that they can resurrect her for one day only and then she must vanish forever — a move that recalls Monica’s initial decision to program David with a capacity for love because she’s granted the capacity to love him in return. The story concludes with their idyllic and implicitly erotic day together (“the happiest day of his life,” says the narrator. “There was no Henry, no Martin”). David recapitulates the story of his life in drawings for a doting but uncomprehending Monica, and she gives him a bath and a seventh-birthday party. Finally David tucks his mother in for good, and we’re told by the narrator that “for the first time in his life” he goes to sleep, lying alongside her and winding up in “that place where dreams are born.”

It sounds like typical Spielberg goo — for better and for worse — and when you’re watching the film it feels that way. But the minute you start thinking about it, it’s at least as grim as any other future in Kubrick’s work. Humankind’s final gasp belongs to a fucked-up boy robot with an Oedipus complex who’s in bed with his adopted mother and who finally becomes a real boy at the very moment that he seemingly autodestructs — assuming he vanishes along with her, though if he survives her, it could only be to look back in perpetual longing at their one day together. Real boy or dead robot? Whatever he is, his apotheosis with Mommy seems to exhaust his reason for existing. As Richard Pryor once described the death of his father while having sex, “He came and went at the same time.” Like the death of 2001‘s HAL, which might be regarded as David’s grandfather, it’s the film’s most sentimental moment, yet it’s questionable whether it involves any real people at all.

Similar paradoxes — soft and hard, warm goo and icy dryness, mother-love ocean (the first thing we hear and see in the film) and chilly waves that drown cities — are in force throughout. The cruelty of humanity and the warmth of David’s yearnings are established as constants, yet it’s in the nature of Spielberg’s fuzzy styling that we don’t always immediately recognize the cruelty — or all of the paradoxes in David’s warmth. It may not be immediately apparent, for instance, that Professor Hobby, a Wizard of Oz figure, isn’t really a nice fellow; he delights in David’s misery because it proves his experiment has worked — even though it’s hinted that he originally created David to fill an aching gap left by the loss of his own son. It’s implied, for that matter, that all robots point to such lacks, absences, and failures in the people who make them, though only at certain junctures does Spielberg encourage us to see that.

One might say that the emotional conflicts experienced by Monica when she first encounters David implicitly remain our own conflicts throughout the film, but Spielberg is too fluid a storyteller to allow us to remember this ambivalence much of the time. He invites us to fool ourselves just as we always do with his films and just as Monica sometimes does with David — a deception based on primal emotional needs and repressed realities. This repression is generally sustained in most Spielberg films, but here the repressed knowledge and emotions periodically come back like icy waves lapping around our ankles.

Sometimes Spielberg’s own dark side comes to the fore, perhaps accounting for the two things in A.I. that I intensely dislike — the depiction of the human crowd at the Flesh Fair and the future beings’ admiration for humans. Both seem to derive from what I often find objectionable in Spielberg’s work. They reek of the influence of Disney’s early cartoon features, especially Pinocchio and Dumbo, and of those films’ ideological imperatives; this undoubtedly adds to the scenes’ primal power, but I also think Spielberg loses control over this movie’s meanings when he chooses such strategies. The brawling human crowd at the Flesh Fair is exclusively working-class — an irrational lynch mob howling for blood, with echoes of the Christian right — which implicitly absolves the middle class and the wealthy, particularly because this scene is meant to make the expulsion of David from the security and comfort of his suburban nest (which has so far dominated the film to the near exclusion of everything else) even harsher. I read this cheesy Mad Max rabble as a truer picture of Spielberg’s view of his audience than we normally get — a view that helps to account for some of the most racist and xenophobic aspects of the Indiana Jones movies. (That the rabble’s targets are machines and not people may justify the violence for some viewers, though the fact that the violence is carried out by rednecks may make it harder to swallow.)

The testimonials to humanity given by the future beings are a prime example of Spielberg’s dishonesty working hand in hand with his fluidity as a storyteller. Their expression of admiration and even envy for the “genius” of humans leads them to conclude, “Human beings must be the key of existence.” This sentiment runs counter to the view of humanity expressed by the remainder of the movie, and I’m guessing that Spielberg inserted it to make his fuzzy beings closer to the people-loving aliens he depicted in Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. Nice try, but such sentiments belong to another movie.

These scenes aside, A.I. is consistently dialectical — almost to the point of schizophrenia and at times to the very edge of incoherence — most often with rich and complex consequences. Take the end of the movie. Is the cloned Monica, resurrected and “corrected” to satisfy a robot’s programmed cravings, much closer to something human than David, created and programmed by man in his own image? Is the love of either character genuine, programmed, or some combination of the two? The line separating life from death, being from nothingness, even the present from the past — “I am…I was,” says Gigolo Joe as he gets hooked and reeled in by a scavenger-police plane like a hapless fish — remains as ambiguous as the line separating orga from mecha or human from inhuman that runs throughout the picture. It’s a line very much like the one separating viewers from the characters in a film or video.

One nice thing about a potential masterpiece with two masters is that it throws the whole question of artistic intentionality — a dubious matter to begin with — straight out the window, because how could Spielberg know precisely what Kubrick intended or vice versa? Yet it’s logical that A.I. should turn out to be an allegory about cinema, regardless of whether either filmmaker consciously had it in mind — not only because both men have devoted their lives to their obsession with cinema, a form of bringing the appearance of life to nonliving matter, but also because the prime issue for the modern world may be our willingness to treat nonliving matter as if it were alive and living people as if they were objects. This issue is raised every time we see someone walking down the street talking on a mobile phone and ignoring everyone else around, every time we hear a mecha voice on a phone or an answering machine, every time we turn on a TV set or computer, enter a movie theater, or start a car, or send or receive an E-mail, or fire a gun. All these extensions of human will — and many others — suggest the same problems and ambiguities.

So reading A.I. as a statement about cinema isn’t much of a stretch. After all, it virtually begins with a woman (who turns out to be a robot in Hobby’s lecture-demonstration) being stabbed and then asked to undress, two movie staples, and it virtually ends with David’s life being transmitted to others in the form of movies and storyboards; the film’s culmination is the ultimate Oedipal movie payoff, complete with all of the lights in the house winking out. Given the heavy investment Spielberg has in single suburban mothers in his oeuvre and his biography, as well as all the implications of a Crate & Barrel version of domestic bliss, it’s the definitive Spielberg conclusion — though it also complements the final sequence of 2001. When the Blue Fairy comes back for an encore inside the suburban home, I’m immediately reminded of the monolith slab reappearing inside the hotel suite just before Bowman gets reborn as the Star Child. Quite possibly this rhyme effect is Spielberg’s doing more than Kubrick’s, because Kubrick, unlike Spielberg, hated to repeat himself or make film references — I can’t imagine him using scavenger mechas to allude to George Romero’s zombies, as this movie does. But the parallel would probably be there in some form even without this underlining. Both locations are mental projections of the protagonist, but whereas 2001 ends with some kind of tragic rebirth, A.I. ends with the implication of some kind of sweet annihilation — something that might also be said to resemble the opium stupor at the end of McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

The problem of distinguishing between what’s real and imaginary is a classic movie theme. The difference between Richard Dreyfuss toying with his mashed potatoes in Close Encounters of the Third Kind and David and his adopted parents laughing at the way Monica eats spaghetti in A.I. is instructive. The first scene asks us to consider the line between obsession and madness; the second asks us to consider the line between mechanical and real laughter — whether it’s human or nonhuman. Each scene has unsettling aspects. But Dreyfuss’s behavior is ultimately justified by the plot — when his mound of mashed potatoes matches a Monument Valley mountain site leading him toward an alien spaceship landing — while the laughter of David and his adopted parents becomes impossible to define as either forced or genuine, mechanical or spontaneous, leaving us perpetually suspended over the question as if over an abyss.

As David, Osment gives a remarkable performance that’s fully attentive to such ambiguities, yet Spielberg keeps ensuring that we periodically forget or overlook some of the more troubling or problematic aspects of his tale — even though a few of them come back to haunt us afterward. This is nothing new in his work. The dramatic success of Schindler’s List largely depends on making us forget or overlook many of the most troubling aspects of the Holocaust, as well as certain aspects of the real-life story that interfere with Spielberg’s patriarchal agenda, such as the fact that Schindler’s wife Emilie played an important role in saving the lives of Jews in Moravia.

In terms of plot, Spielberg has made the final sequence of A.I. somewhat incoherent so that he can articulate his Oedipal idyll as cleanly as possible. It’s similar in some ways to the terrain explored in Solaris — an inquiry into what it means to be human and what it means to die — without the spiritual side of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Christian mysticism. And most of what gets repressed at some point in the film is articulated in another, so that the movie constantly swings between dizzying uncertainties and grim — or is it exalted? — finalities. It’s part of this movie’s richness that few of its contradictory ideas and emotions cancel one another out. Instead they congeal into a kind of poetry — a term I wouldn’t ordinarily use to describe either director’s work — whose melancholy, forlorn pungency is paralleled in the Yeats lines quoted at the penultimate stage of David’s odyssey:

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping

than you can understand.