From the April 2017 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

FILM IS LIKE A BATTLEGROUND

Sam Fuller’s War Movies

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Marsha Gordon. Oxford University Press, 314 pp. £24.07, ISBN 9780190269753

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Some Samuel Fuller fans may find it surprising that

the two most substantial academic studies of him so

far have both been by women—Lisa Dombrowski’s 2008

The Films of Samuel Fuller: If You Die, I’ll Kill You! and

now Marsha Gordon’s more specialised volume. But for

anyone lucky enough to have known Fuller personally,

isn’t surprising at all. An unabashed feminist whose

feisty mother remained a key figure for him, Fuller

confounded macho stereotypes as much as those

associated with familiar ideological and Hollywood

patterns, even while remaining a feverish self-mythologizer.

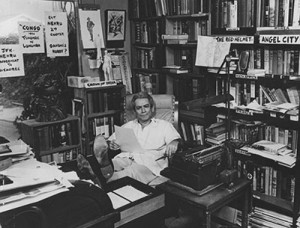

Gordon’s principal strength is as a researcher, and her access to such items as Fuller’s letters home and diaries during his wartime service and some of his lesser-known publications, productions, and projects (such as a 1944 magazine story, an unsold 1959 TV pilot called Dogface with some striking anticipations of his White Dog, and his subsequent unrealized screenplay The Rifle) allows her to treat her elected subject with a great deal of thoroughness. For its illustrations alone, this book offers a fascinating Fuller scrapbook. Perhaps Gordon’s biggest scoop, noted in her Introduction, is the fact that Fuller wasn’t born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1912, as he often claimed and may well have believed, but, as a Russian Jewish immigrant with the name Michal Filler, was born ‘sometime in 1911’ and emigrated to the U.S. from ‘Wladimir, Russia’ on the SS Canada in 1913, at the age of one and a half.

Given the centrality of his war experience, one could argue that most or all of Fuller’s films qualify as war movies in one way or another. But Gordon chooses to be more selective—starting with the silent 16mm film Fuller shot in 1945 during the liberation of a Czech concentration camp in Falkenau, and ending with Emil Weiss’s 1988 documentary Falkenau, the Impossible (in which Fuller comments on the same film). In between we get separate chapters on The Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets; Pickup on South Street and Hell and High Water (as “Cold War Stories”); China Gate and The Rifle; Verboten!, Dogface, and Merrill’s Marauders; and The Big Red One (focusing on the 1980 release, not the 2004 expanded version). I might have opted for Park Row, where the various intrigues are distinctly warlike, but am still glad that she happily managed to shoehorn Run of the Arrow into her Introduction.

A more serious gap is her reluctance to treat Fuller’s stylistic and thematic bravado in greater detail, perhaps as a result of her academic decorum. Although she rightly calls Fuller’s muddled claim — that the madness of Sgt. Zack (Gene Evans) after shooting a POW in The Steel Helmet is some form of moral retribution—‘unconvincing’, I wish she had more to say about how central that madness is to Fuller’s ongoing sense of war’s contradictions. She’s very good in tracing the autobiographical sources of Fuller’s first (and for me, best) Hollywood war film, and adept at showing how the movie was assailed with equal vehemence from both the left and the right. Yet she’s less commanding when it comes to treating its philosophical rage and its formal bluntness.