This appeared in the August 21, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Nights of Cabiria

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Federico Fellini

Written by Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and Pier Paolo Pasolini

With Giulietta Masina, Franca Marzi, Francois Perier, Amedeo Nazzari, Dorian Gray, and Aldo Silvana.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Reporting on the response to Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria at Cannes in 1957, François Truffaut wrote, “Let us deplore the fad that seems to be shared equally by the audience, producers, distributors, technicians, actors, and critics who fancy that they can contribute to the ‘creation’ of the films being shown by deciding how they should have been edited and cut. After each showing, I’d hear things like ‘Not bad, but they could have cut a half-hour,’ or ‘I could have saved that film with a pair of scissors.'” As festival responses to more recent masterpieces like Taste of Cherry and The Apostle have shown, this fad is still very much with us. Another, more recent fad is to release longer versions of films that were butchered on their release. Too often these so-called director’s cuts — such as Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and the forthcoming Touch of Evil — can’t qualify as restorations, however, because the directors were never accorded final cut in the first place.

A better candidate for a “director’s cut” is the longer version of Nights of Cabiria playing at the Music Box this week. A single short sequence cut after the film’s Cannes premiere — reportedly due to pressure from the Catholic church, commercial considerations, and perhaps the comments cited by Truffaut — has recently been restored thanks to Bruce Goldstein, a programmer at New York’s Film Forum. But this brief episode alone has led me to reevaluate the film and as a consequence make some discoveries about Fellini’s work as a whole. And ultimately the sequence resonates with some previously questionable portions, creating a much richer and stranger film. It strikes me as both astonishing and characteristic that we’ve waited 41 years for this to become evident.

I should confess that most of Fellini’s work (he died in 1993) has posed a problem for me. It’s not that I contest his talent but that it’s difficult to separate his invention from his shameless pandering to the audience, which involves cornball rhetoric, demagoguery, and other excesses at the expense of artistic judgment; Steven Spielberg is a similar but even more flamboyant showman. It becomes difficult to praise the invention without endorsing the regressive baggage as well. And, as with Spielberg, that baggage is often tied to innocence — the audience’s as well as the filmmaker’s. “Fellini is essentially a small-town boy who’s never really come to Rome” was Orson Welles’s apt way of putting it. “He’s still dreaming about it. And we should all be grateful for those dreams.” Indeed we should. But when a filmmaker’s boyish dreams are praised as the hard-won, disillusioning discoveries of an adult — as they have been praised in Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan as well as Nights of Cabiria — the audience’s innocence cries out for correction.

Part of the innocence at issue in Nights of Cabiria is the result of the Chaplinesque mugging by Fellini’s wife, muse, and medium Giulietta Masina — a dated, aggressive form of pantomime that was a point of critical contention even back in the 50s, recalling as it does a performance style of the 20s. For all the undeniable pathos and animation of Masina’s doll-like features, Fellini often uses them in La strada and Cabiria as blunt emotional instruments intended to beat the viewer into submission — and without the nuance that Chaplin brought to comparable tasks. Even if one recognizes and applauds Fellini’s corresponding impulse to return to the elemental purity of silent film, the related narrative simplifications have an overall coarsening effect, falsely implying that silent cinema was also invariably crude in this manner.

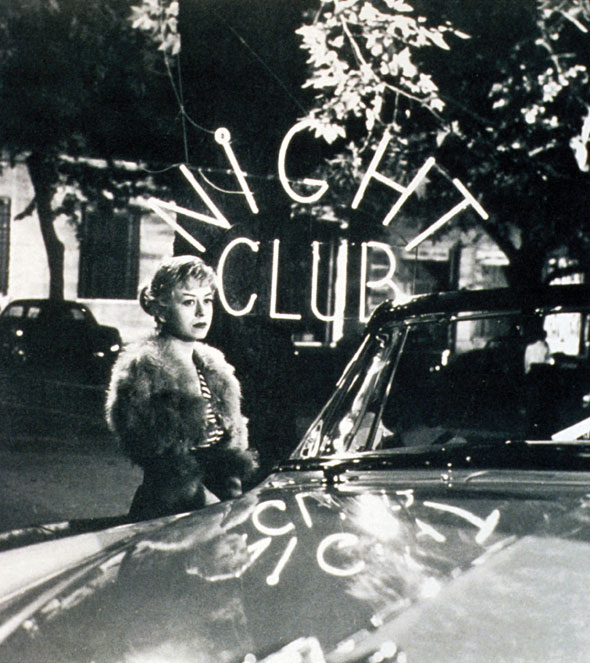

Fortunately, Nights of Cabiria improves on La strada in one respect: alternating with Masina’s waiflike credulity is the brittle skepticism of her character, a prostitute who goes by the street name of Cabiria. Pier Paolo Pasolini was enlisted to supply her and her fellow prostitutes with Roman street slang, and as a result the film oscillates between authentic grittiness and dreamy flights of fancy — rather as Cabiria herself does.

There were several points in Fellini’s career when nonnarrative drift overtook narrative flow and story gave way to spectacle. But a major part of this transition occurred about halfway through his oeuvre, as the protean personal allegory of the 1963 8 1/2, a masterpiece, was transformed into a mere catalyst for various visual effects in the 1965 Juliet of the Spirits, a sort of congealed circus in which Masina plays the allegory’s protagonist. This was followed by various works of episodic drift and spectacle like Fellini-Satyricon, Fellini’s Roma, Amarcord, Fellini’s Casanova, City of Women, And the Ship Sails On, and The Voice of the Moon, the sort of films that dominated the remainder of his career. One could just as firmly describe the seven Fellini features preceding 8 1/2 (Variety Lights, codirected by Alberto Lattuada; The White Sheik; I vitelloni; La strada; Il bidone; Nights of Cabiria; and La dolce vita) as mainly driven by their stories.

Juliet of the Spirits was the third of Fellini’s features that gave top billing to Masina, but one could argue that it was the first that starred Fellini himself rather than his wife. The filmmaker’s subjective take on his wife’s subjectivity revealed the limitations of his vision, and that’s what made the film overall so problematic: the putative subject ended up drowning in Fellini’s style. The incorporation of his name into the titles of some subsequent features was only the next logical step. Most of the rest of his films tended to have subjects rather than stories — not a bad thing in itself, though it renders any decisions about when to start the film and when to end it relatively arbitrary. In Juliet of the Spirits, this tendency reduced Masina’s mannered style to its worst aspects; as Manny Farber noted at the time, “Her sexless acting is a parlay of Bambi’s stiff motion, Harry Langdon’s large ball-bearing eyes, and Spring Byington’s ability to exude goodness, patience, and domestic cleanliness with a raspberry valentine smile.”

Sometimes the transition between story and spectacle in Fellini’s work takes place less on-screen than in the mind of the beholder. For me there’s a clarifying moment of this kind in Nights of Cabiria, when such a sea change takes on unusual force, transforming everything leading up to it as well as everything following it. And oddly enough, without the restored sequence — which figures somewhat earlier — this moment doesn’t have quite the same impact.

One off-putting aspect of the movie is that it’s driven less by plot than by five extended episodes in which Cabiria moves from hope to disillusionment. You might even say that formally this pattern reflects a repetition compulsion, though it has thematic ramifications. The restored sequence, which is shorter and seemingly less consequential than the others, breaks with this pattern by moving from disillusionment to hope, as does the film’s even shorter final sequence.

In the first episode, Cabiria is pushed into a river by a boyfriend who steals her purse; in the second, she’s picked up by a movie star who’s had a fight with his girlfriend, then gets shunted off as soon as the girlfriend returns. The restored interlude occurs just after this point — Cabiria encounters a man with a sack in a wasteland delivering clothes and food to homeless people, who live in holes in the ground; one of them is a former prostitute, now an old woman, whom Cabiria recognizes. Cabiria is clearly moved by the man’s selfless mission, and after he gives her a lift back to Rome, she reveals her real name — Maria Ceccarelli — for the first and only time in the film, leaving him with the words, “Thank you, thank you for everything.”

It’s been conjectured that this interlude was cut in 1957 because the Catholic church didn’t approve of representing this kind of charity outside its own auspices. Indeed, the third of the original episodes at least implies a further criticism of the Church when it shows Cabiria traveling with other hookers, a drug-dealing pimp, and his crippled uncle to a shrine of the Madonna of Divine Love, hoping for a spiritual release she doesn’t find.

The transformative moment takes place in the fourth of the original sequences, when Cabiria attends a magic show in a suburban movie theater where she’s coerced into joining the act — hypnotized by the magician into believing that she’s being courted as a young girl by a suitor named Oscar. Partly because of the theatrical setting and partly because Cabiria is a highly skeptical spectator both before and after she falls into her trance, the scene becomes an emblematic representation of moviegoing itself — what it typically promises and just as typically fails to deliver. (Of course prostitutes, who must pander to the fantasies of their clients, perform a function similar to that fulfilled by movies.)

This representation is strengthened in the fifth episode, when Cabiria meets another spectator after the show, Oscar, who proceeds to court her, taking her to a movie on one of their outings. Oscar is the center of this, the film’s final extended episode, which is even more melodramatic and contrived than the others. But thanks to the preceding sea change, it seems less story than spectacle. If the first three long episodes in Cabiria use spectacle in order to tell a story, the last two use story in order to create spectacle. The difference is metaphysical rather than merely a matter of semantics: stories imply progression, but spectacles imply unchanging states. In this case the character who started out as a picaresque heroine winds up as a kind of essence, an essence that can survive and even prevail over disillusioning stories. In this way Cabiria is a metaphor for the childlike gullibility or faith that makes Fellini’s dreamlike cinema possible, even when a film’s narrative underpinnings come loose.

The restored sequence of the man with the sack is crucial because it’s the first indication in the film of an essence comparable to Cabiria’s. It also makes sense that this is the only point when Cabiria reveals her real name; the man’s essence brings her own to the surface, allowing us to catch a fleeting glimpse of it. The great French critic André Bazin — who wrote more perceptively about the film than anyone else, stressing the central importance of this sequence and protesting its deletion after the 1957 premiere — described it this way: “When one stops and reflects, one realizes that there is nothing in the film, before the meeting with the benefactor of the tramps…which is not proved subsequently to be necessary to trick Cabiria into making an act of ill-placed faith; for if such men do exist, then every miracle is possible and we, too, will be without mistrust when [Oscar] appears.”

It was Bazin, too, who defended the short, sublime, hopeful end of the movie as the source of the viewer’s liberation. He describes a moment when “Masina turns toward the camera and her glance crosses ours ….The finishing touch to this stroke of directorial genius is this, that Cabiria’s glance falls several times on the camera without ever quite coming to rest there….Here she is now inviting us, too, with her glance to follow her on the road to which she is about to return. The invitation is chaste, discreet, and indefinite enough that we can pretend to think that she means to be looking at somebody else. At the same time, though, it is definite and direct enough, too, to remove us quite finally from our role of spectator.” The gift of Cabiria’s essence, freed from the determinism of stories, is to return us to our own.