From the August 3, 2001 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

This month the Film Center is inaugurating a monthly “Music Movies” series, five programs that will play on Sundays and Thursdays. The focus in August is jazz films, and the programs include four classics I first saw years ago and four others I’ve just seen for the first time. The worst film in the bunch (Cannonball) happens to be the newest one, and the two most interesting (Cry of Jazz and Black and Tan) are the oldest, though I don’t see any particular trend in this.

It’s difficult to speak of any consistent evolution or devolution in jazz films, because each one is the product of a particular taste and sensibility. One rule I use when evaluating these films is how much we’re allowed to follow the music. Another rule, less obvious and more purist, is how important the on-screen listeners are — which matters a good deal, because jazz at its most exciting is a collective experience involving the audience as well as the interacting musicians. If the people on-screen aren’t seen listening when music is being played, we’re discouraged from listening intently.

This helps explain why I was driven batty by the new 23-minute video about Cannonball Adderley, a musician who has given me a lot of pleasure. Cannonball: The Life and Legacy of Julian Adderley, showing on August 12 and 16 with the excellent hour-long Mingus, starts with Adderley playing “Work Song” — a solo that’s almost immediately smothered by a voice-over explaining, “His legacy would have to be as one of the greatest alto saxophonists who ever lived.” Yeah, thanks a lot, I muttered to myself. A few bars later the video cut to someone else offering an equally unhelpful superlative, and then the solo was rudely interrupted by another arbitrary cut. Nobody was listening because everyone was too busy talking — the subject’s living legacy had been relegated to the background.

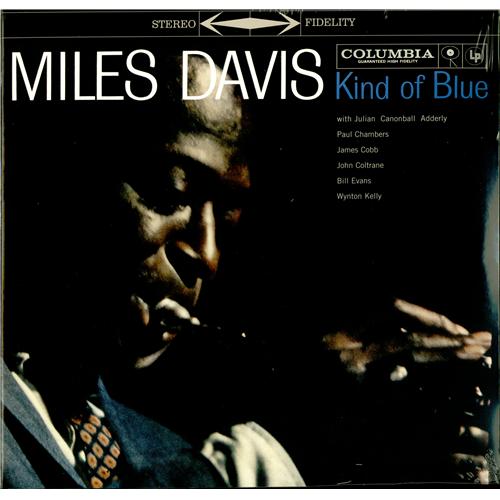

I hasten to add that if you want to learn a little bit about Adderley’s life — about, among other things, his involvement in the civil rights movement and his struggle with diabetes — this video won’t let you down. But it seems symptomatic that the three directors — all of them graduate students at the University of Florida, in Adderley’s home state — wouldn’t dream of interrupting an unexceptional poem recited on-screen at regular intervals (“A cannonball was propelled at us…”), yet they keep interrupting their hero every time he picks up his horn. And when record producer Orrin Keepnews talks about Adderley joining the Miles Davis Quintet to make it a sextet between 1957 and 1959, culminating in the Kind of Blue album, there’s no connection to the lovely up-tempo Adderley number in the background, Duke Pearson’s “Jeannine,” which is also cut off midsolo. Perhaps the cost of getting clearance to use the music was responsible, but even the music that is used tends to be chopped up in a nonmusical fashion.

None of these problems show up in Thomas Reichmann’s Mingus (1968), but then Reichmann knew bassist-composer-arranger Charles Mingus and followed him around with a camera — at club dates, in the park, in his apartment (where Mingus occasionally plays piano and sings along, sometimes with his little girl in tow), and eventually out on the street when he was being evicted. Mingus took advantage of Reichmann’s presence, holding forth, musically as well as verbally, and often turning out to be his own best listener. Sometimes he goes too far in exploiting the situation, as when he brandishes a rifle and fires a hole through his ceiling, seemingly out of boredom or simple perversity. But the man and the music both come across loud and clear, and there are few jazz personalities as striking or as multilayered.

We don’t always hear numbers or even solos all the way through, but Reichmann always cuts away for a reason and never bends the music out of shape. If he frustrates expectations, it’s only to satisfy them later. My favorite Mingus tune, “Peggy’s Blue Skylight,” is played in so many consecutive installments between segments of his talk I thought we’d never get to the song’s B theme, its loveliest stretch; but when Reichmann finally took us there, it was a genuine arrival — a luxurious flop down at the end of a journey.

I was living in Mingus’s Greenwich Village neighborhood in the late 60s, and I saw a lot of him — at his club dates and those of other musicians and on the street. Once he even showed up at my door after he’d been evicted, looking for my landlord and hoping for an apartment. The man I remember seeing is totally present here with all his anger and passion, his intelligence and his virtuoso bass playing. Of all the jazz portraits on film I can think of, this is the one most clearly shaped by the film’s subject, moment by moment, and Mingus makes it full of as many mood swings and tempo changes as one of his own compositions.

The series opens on August 5 and 9 with a classic, perhaps the best of all jazz documentaries when it comes to showing people listening. Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1960) is still photographer Bert Stern’s only film, shot in luscious color. It takes in several groups at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, but Stern has more fun with the responses of the audience — how people move (or don’t) with the beat and other forms of engagement or disengagement — which are an important part of our pleasure, sometimes even a part of the music. But on other occasions he simply gets bored with the musicians and listeners alike and cuts away to a boat show or another local event, real or contrived, often while the music continues offscreen.

Stern has admitted that he’s never been a jazz fan. The choice of what groups to film was made by Columbia Records’ George Avakian (more, it seems, for business than aesthetic reasons), though Stern says that if he’d made the decisions he wouldn’t have included Miles Davis either, because “he’s too far out for me.” Stern seems incapable of distinguishing between good, bad, and mediocre jazz, so it isn’t surprising that some of the top musicians here — such as Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, and George Shearing –aren’t seen in top form. In much better fettle, especially as camera subjects, are Jimmy Giuffre, Anita O’Day, Louis Armstrong, and Mahalia Jackson.

The film in the series with the best all-around playing (Mingus takes second place) is Thelonious Monk: Straight, No Chaser (1989), showing on August 12 and 16. Most of the footage was shot in black and white in 1967-68 during Monk concerts and studio sessions by German documentary filmmakers Michael and Christian Blackwood; it was discovered two decades later by Bruce Ricker — a tireless maker, promoter, distributor, and facilitator of jazz films, who understandably called this priceless material “the Dead Sea Scrolls of jazz” — then Charlotte Zwerin turned it into a feature with supplementary interviews and footage of two other pianists playing Monk tunes.

The film has more interruptions, voice-overs, and unnecessary tangents than I would have liked, but the biography keeps intact the mystery of one of the most enigmatic figures in jazz. And the overall organization of the musical material is superb: we get bits of three separate performances of “Rhythm-a-ning” and two of “Evidence” that build on one another, and many of Monk’s other best tunes — including “‘Round Midnight,” “Well You Needn’t,” “Epistrophy,” and “Off-Minor” — are salted through the proceedings. Monk expresses what and how he hears even better than Mingus does — through dancing, most often just before or after his solos. And the playing itself, by Monk and his sidemen, is often extraordinary.

Back in my New York days, I went repeatedly to hear Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Roland Kirk, Mingus, Monk, Cecil Taylor, and Lennie Tristano (with Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh). I went to hear Sun Ra only once, because the experience seemed more theatrical than musical; today I can only vaguely recall what his group looked like, not how it sounded.

This helps explain why I don’t consider John Coney’s 63-minute video Space Is the Place (1974), playing at the Film Center on August 26 and 30, a jazz work. It features Sun Ra turning up in Oakland after years in outer space — and after a prologue set in 1943 Chicago — rapping with ghetto youths, and playing cards with the devil. It makes for pleasant enough viewing as lighthearted surrealist high jinks with some SF trappings and some black-power rhetoric, but the music seems strictly incidental.

By contrast, the music in Edward O. Bland’s accompanying half-hour, Chicago-made short Cry of Jazz (1959) — which also features Sun Ra and his Arkestra — is absolutely essential. The paradox here is that Bland’s film is centrally about jazz and needs various kinds of jazz performances to illustrate most of its points, yet what’s being played is only adequate. But if the jazz were a lot better — good enough to distract one from the talk — it wouldn’t work as well. I recommend Cry of Jazz without hesitation to any jazz novice, because it’s one of the best social readings of jazz form I know, lucid as well as provocative.

It’s also quite dated, though this adds to its interest. For the past 40-odd years I’ve been hearing this didactic film characterized as an antiwhite polemic, which isn’t so much wrong as incomplete, for it’s also implicitly integrationist. Most of it takes the form of an impromptu lecture on jazz at an informal interracial gathering, delivered by a black musician named Alex (George Waller) to white friends. He argues, among other things, that whites can be great jazz players only if they’ve suffered as much as their “Negro” counterparts.

Such an analysis may fail to account for the genius of someone like the white tenor sax player Warne Marsh — whose recent biography by Sanford Chamberlain suggests he was a creditable successor to Lester Young and Charlie Parker, even though he suffered less than either of them. But it does go a long way toward describing some of the emotional as well as ideological implications of the music within a black context.

Describing jazz form as a dialectic between “restraint” (exemplified by the chorus and recurring chord changes, two kinds of “endless repetition” that mirror confinement in the ghetto) and “freedom” (“melodic improvisation” and “rhythmic conflict,” both reflections of “the improvised life forced on the [American] Negro”), Alex winds up analyzing the music and its social background at the same time. The suggestive notion of repeated patterns reflecting confinement and improvised variations — willed or reactive — reflecting freedom could be applied to the music in other ways as well, but the dialectic seems basic to jazz, however one articulates it.

Bland’s clunkiness in directing actors, like the political incorrectness of his script (cowritten with Nelam Hill, Mark Kennedy, and Eugene Titus) in matters involving gender as well as race — women musicians don’t exist even theoretically in Alex’s discourse, and, if I’m not mistaken, black women aren’t in evidence at this interracial gathering — seem much less important than the perceptiveness and honesty about the existential stresses of the music. Bland has found a fruitful way of dealing with the effect of listening to jazz as well as playing it, and this has sustained the film’s interest over more than 40 years.

I would argue that Dudley Murphy’s extraordinary 19-minute Black and Tan (1929), with Duke Ellington in his first film appearance, needs to be approached in a similar frame of mind rather than scorned for its racial stereotyping. That stereotyping — which involves two dim-witted black comics sent to repossess Ellington’s piano, one of whom demands of the Duke, “Remove your anatomy from that mahogany,” and both of whom get bought off with a bottle of gin — dominates only the opening sequence and is every bit as unexceptional for 1929 as the uses of “Negro” and masculine pronouns are for 1959.

Black and Tan is playing with Robert Drew’s serviceable TV documentary On the Road With Duke Ellington on August 19 and 23. Drew shot his film in 1967 — the year Ellington picked up honorary degrees at Yale and Morgan State College and the year Billy Strayhorn, his principal collaborator, died — and slightly updated it in 1974. It’s valuable mainly for the portrait it offers of Ellington as a person, pianist, and composer, in roughly that order, though not so much as a bandleader. Insofar as Ellington’s main instrument was his orchestra, this is a limitation, but On the Road is still valuable for giving us aspects of the man neglected elsewhere. We learn that he started every day with a cup of hot water rather than coffee or tea and that he composed a lot of fugitive pieces for his band that were performed in public only once and never recorded, one of which we hear. We also see him performing a few of his standbys; “Take the ‘A’ Train” is played with his band on a train in a clip from the 1943 Hollywood musical quickie Reveille With Beverly, then as a waltz on piano in 1974, and finally in a more up-tempo 4/4 extended solo around the same time. In the latter solo the camera focuses not on the keyboard but on Ellington’s features as he listens and responds to his own playing, providing us with a kind of intimacy we don’t ordinarily get in his film appearances. (Bearing in mind that he was Mingus’s main influence as a composer, the views we get of Mingus noodling at the piano in Mingus and Ellington in this film are quite complementary.)

Only three of the works in this series — Jazz on a Summer’s Day, Cry of Jazz, and Black and Tan — are interesting as films and not merely as documents, and only Black and Tan qualifies as a masterpiece. Yet the master in question, Murphy (1897-1968), remains a shadowy figure. William Moritz wrote the only article I know of about his work — “Americans in Paris: Dudley Murphy and Man Ray,” included in a 1995 collection called Lovers of Cinema: The First American Film Avant-Garde, 1919-1945 — but he doesn’t seem to have seen Black and Tan at the time he wrote it. A reproduced production still identifies Murphy, Ellington, and author Carl Van Vechten (a notable white Harlem groupie of the period), but not dancer Fredi Washington, the film’s leading character, who’s identified by her own name in the dialogue. [2009 postscript: An excellent book on Murphy — Susan Delson’s Dudley Murphy, Hollywood Wild Card — was published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2006.]

Murphy also shot an early sound short with Bessie Smith (St. Louis Blues) around the same time, codirected the famous Ballet mécanique in Paris with Fernand Léger five years earlier, and directed The Emperor Jones with Paul Robeson four years later. He has a filmography of 39 titles, including Hollywood as well as independent work, and he worked in Mexico as well as France and the U.S.; he even wrote the dialogue for the 1931 Dracula. It’s a rich and varied career that deserves to be resurrected.

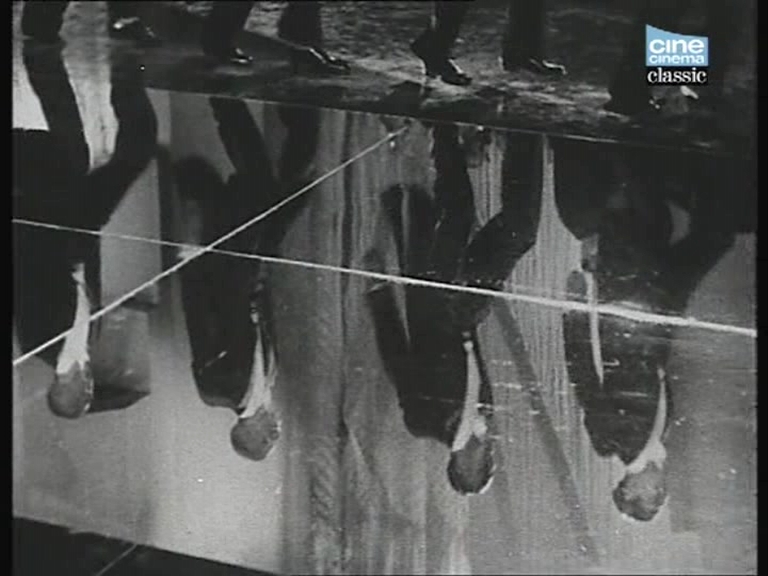

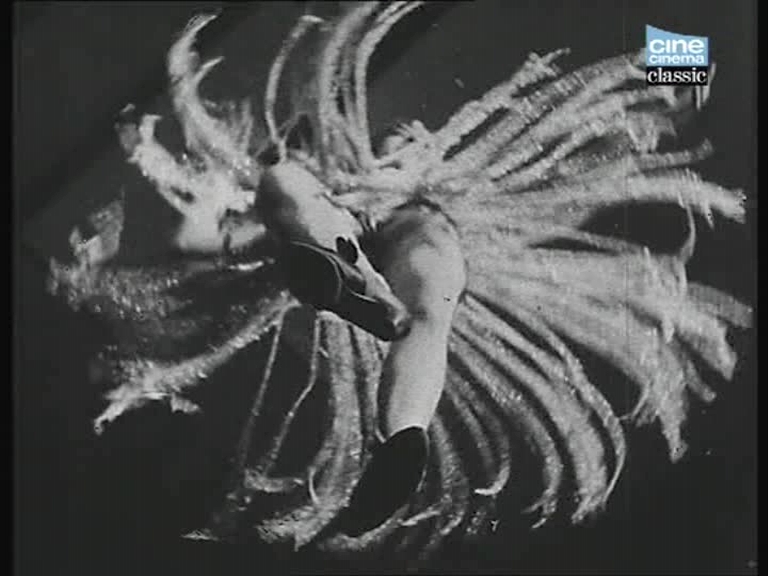

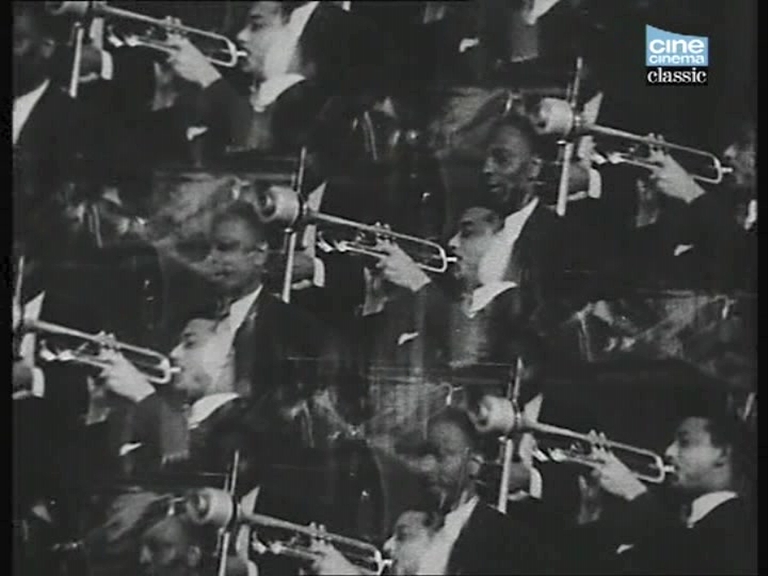

Black and Tan opens with Ellington rehearsing his “Black and Tan Fantasy” at home with trumpet player Arthur Whetsol — his detailing of the arrangement to Whetsol sounds quite authentic — before the repo men turn up and are bribed with gin by Washington. The scene switches to the white club where Ellington and his band are performing — along with several black dancers, including Washington, who’s ill with a heart condition but is pressured to go on anyway — and we get several images of endless repetition that anticipate Bland’s notions of restraint in jazz. The dancers all perform to Ellington’s music on a mirrored floor so that we see everything they do in duplicate, and the first number with several male dancers is repeated so that we can see it again from Washington’s feverish and hallucinated perspective backstage — a beveled, kaleidoscopic image that’s echoed when she goes into her own dance. (Murphy also throws in a startling low-angle shot of her through the glass floor.)

She collapses in midnumber, and after she’s hurriedly carried off, the floor manager gets the band to start playing again for another group of dancers. At first Ellington obliges, but then he abruptly halts the band and the members all leave the club. The final sequence shows the whole band in silhouette playing “Black and Tan” for Washington at her request, crowding around her bed while she dies.

The close-ups of her listening to them are the most powerful reactive images I know in any jazz film. They’re followed by another remarkable point-of-view shot showing Ellington at her side as he gradually becomes blurry, fading like a guttering candle; uncannily and beautifully, this blurred shot returns after she dies, as if to underline the persistence of her gaze and by extension the continuation of what she hears.

Murphy was white and Bland is black, yet the racial politics of Black and Tan are more radical in at least one respect than those of Cry of Jazz. The 1959 film is integrationist in its social context, being set at a “mixed” party, but the 1929 film is just as clearly separatist in its conclusion, implying that black people may be finally the only ones who deserve to listen to their own music (ironically, the growling “Black and Tan Fantasy” — extended by solos on trumpet, trombone, and Barney Bigard’s piercing clarinet — quotes the Funeral March from Chopin’s second piano sonata). The white audience members are never seen, though we hear their applause. And the mirrored images of band and dancers, like the deathbed lullaby performed for the exploited Washington, intensifies our sense of artists appreciating their own work as well as one another’s, as only artists can.