From the Chicago Reader (January 4, 2002). — J.R.

There is no such thing as film production. It is a joke, as much as the production of literature, pictures, or music. There are no good years for films, like good years for wine. A great film is an accident, a banana skin under the feet of dogma; and the films that we try to defend are a few of those that despise rules. — Jean Cocteau, 1949

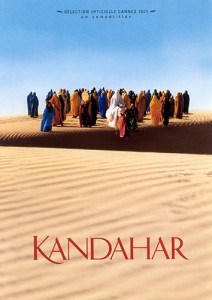

Two events in the year 2001 changed my relation to movies — one public and momentous, the other private and relatively trivial. The public event, of course, took place on September 11, and for many Americans, myself included, it broadened dramatically what we mean when we say “us.” It changed the way we see the world as well as the U.S., and for me the change in the way we see the world was more important. Some of my compatriots may still not be able to move mentally beyond this country, even theoretically; others may be considering the possibility for the first time. I saw better than ever the role movies can play in helping us understand the world from other perspectives, and the sudden outpouring of interest in films about Afghanistan — most notably Jung (War): In the Land of the Mujaheddin and Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar — was only the most obvious sign that this is happening.

The relatively trivial private event that changed my relation to movies was buying a DVD player, which gave me a new alternative to cinema as a public activity. My machine has the capacity to play DVDs from different parts of the world, which is valuable because the film industry divides the world into territories, selling the rights to films to each territory individually and distributing copies to each that can’t be played in the others. Industry spokesperson Jack Valenti might see having a DVD player that can handle all the territories — such machines are far more common outside the U.S. than inside — as a brazen act of aggression against American business interests, but my friends around the world say it allows people to get a version of film history that’s not controlled and monitored by American business interests. DVDs can supplement our sense of film history, important at a time when less and less restoring is being done, a time when public funds for culture are being slashed.

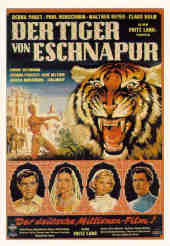

They have already given us access to films that can’t be found in theaters. Fritz Lang’s glorious 1959 two-part feature, consisting of The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb, has never had a commercial run in the U.S. (unless you count a week at a New York art house in the early 80s), but now you can readily order both parts here on DVD, with excellent liner notes by the University of Chicago’s Tom Gunning. And some of the best film criticism I encountered this year consisted of offscreen commentary by the University of Chicago’s Yuri Tsivian on superb DVD editions of Dziga Vertov’s The Man With the Movie Camera and Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible. But I had to order from France the DVDs of Joe Dante’s The Second Civil War, Alain Resnais’ Stavisky…, the restoration of Louis Feuillade’s 1913-’14 Fantomas serial, and the deluxe edition of Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, which features many discarded scenes and sequences (and is supposed to come out here eventually).

Obviously, DVDs aren’t a perfect source for film history. The copyright holder of Orson Welles’s 1952 Othello is his daughter Beatrice, who chose to rerelease the film in 1992 with all its music and sound effects reworked. She had a golden opportunity to release that version of the film alongside her father’s on a single DVD — if she believed in her version enough to show everyone what the differences were. Instead she elected to release only her version, keeping her father’s out of reach. Yet another DVD has made most of a documentary TV series by Welles, Around the World With Orson Welles, available in this country for the first time — an event virtually unheralded in the mainstream press and film magazines, which were far more interested in an upcoming made-for-TV boondoggle that ludicrously purports to be based on Welles’s original script for The Magnificent Ambersons. (Having spoken at length to a reviewer who’s seen it, I gather that, among other things, the narration and final sequence were removed to make way for flashbacks and a happy ending — none of which was in the original.)

Whether you view the world (or movies) from a local or global perspective — though many people I know think globally but feel locally, especially New Yorkers traumatized by September 11– determines to some extent what you see. I’m making a distinction not just between American and foreign works, but between American mainstream and nonmainstream works that have some global meaning apart from a capacity to make money. From the perspective of the American mainstream media, one of my favorite films of the year, The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein, can barely be said to exist, because it has no distributor and hasn’t been shown in either New York or Los Angeles — which is becoming the ultimate proof of existence. It has, however, been shown at several low-profile film festivals — in Austin, Taos, Buenos Aires, Chicago, and other places, in the U.S. and Europe. There’s no reason to feel guilty if you haven’t seen it — no critic on the planet has seen all the best movies of 2001, and those who claim otherwise are lying through their teeth.

To a scandalous extent, what qualifies as a contender for mainstream ten-best lists depends on publicity budgets and seemingly arbitrary distribution deals and dates. Many friends and colleagues urged me to catch up with Donnie Darko (which Lisa Alspector reviewed in a capsule in the Section Two film listings), but no videos were made available. Yet I could have watched an atrocity like The Majestic endlessly if I’d wanted to, because two copies arrived in the mail. Gosford Park is practically the only Robert Altman film I’ve cared for since the 70s, but it didn’t open commercially in Chicago in 2001. The only reason I managed to see A Huey P. Newton Story, Spike Lee’s filming of a remarkable performance piece by Roger Guenveur Smith for TV, is that I happened to catch a screening at the Vancouver film festival. Michael Haneke’s impressive and innovative Code Unknown played in Chicago last year only on the Sundance Channel — though it opens at the Music Box this week — and I finally caught up with it two nights before Christmas. And the list goes on.

***

Emotional, conceptual, and perceptual confusions of various kinds are at the root of my two favorite pictures of the year — both American, both released by big studios, and both offering experiences so disorienting they alter the definition of movies more profoundly than any DVD extras can. I’ve considered them, like the other films on my list, as a group. (I should explain that The Day I Became a Woman, George Washington, and The Gleaners and I, which had commercial runs here in 2001, aren’t on this year’s list because they were on my list for last year.)

1 and 2: A.I. Artificial Intelligence and Waking Life

For starters, both movies confound habitual assumptions about authorship and intentionality. For all its personal elements, is A.I. just a movie by Steven Spielberg, as so many reviewers have been insisting? It can be taken that way, but only at the cost of missing much of what’s provocative and challenging about it. Similarly, one can see Waking Life as simply a Richard Linklater film only if one rules out Bob Sabiston, who designed the software program that made its animation possible, and the 30-odd artists who implemented the program. I wouldn’t call A.I. simply a posthumous work by Stanley Kubrick either, though I wouldn’t rule out that dimension — which is clearly what motivated Kubrick’s widow and brother-in-law to persuade Spielberg to take over the project and is part of what motivated Spielberg. Indeed, I suspect that Spielberg approached this project with more seriousness and more willingness to show fidelity to its source than he did when approaching the Holocaust or Oskar Schindler’s life for Schindler’s List. His limitations are still apparent in spots, but this film makes the usual distinctions between success and failure seem trivial.

Pretty much the same holds for the dramatic construction, dialogue, and animation of Waking Life, because whenever any of these pieces falters, the film’s conceptual strength — a sense of existential identity and place that exists beyond the parameters of “objective” photography, and the notion of animation itself as a kind of dreaming with profound links to our waking life — is still strong enough to carry them. A.I. is about the ambiguous differences between human and nonhuman; Waking Life is about the ambiguous differences between real and imaginary. These are two sides of the same ontological issue, which I see as the primary issue for both technology and the media, including film. Despite the misanthropy of A.I. (which I associate with Spielberg as much as Kubrick, regarding 1941 and Barry Lyndon as two sides of the same coin), the film made me cry. And despite the ingenuousness of many of the bull sessions in Waking Life (which I tended at times to regard as musical accompaniment), the movie made me think. As a whole, audiences appeared to have an easier time with the innovations of Waking Life. In contrast, legions of viewers felt comfortable only with the middle section of A.I., wished the film had ended with the Blue Fairy, and preferred the pat ironies of Gigolo Joe (Jude Law) to the confusing emotions aroused by the lead mecha (a superb Haley Joel Osment); they seemed to be hankering for the sort of Spielberg film they already knew. Anyone who found this one merely sentimental wasn’t paying close enough attention to the bleak and bitter undertones.

At the Savannah film festival I was fascinated to see some of Waking Life‘s initial live-action DV footage on Sabiston’s laptop, and I hope that samples of this material will be included on the film’s DVD. A.I.‘s DVD is slated to be released in April, and I’m sorry it apparently won’t include any of the 90-page Ian Watson script written for Kubrick that served as Spielberg’s main source — though it reportedly will include a few of the 600 drawings by Chris Baker that Kubrick also commissioned.

3, 4, and 5: The Circle, ABC Africa, and The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein In their transcendental American manner, A.I. and Waking Life are too grounded in philosophical quandaries and too socially alienated to qualify as being directly political. But these three features — the first two by Iranians, the third by an American independent — are too concerned with suffering and where it comes from to be content with metaphysical reflection. This doesn’t mean they aren’t concerned with beauty and shapeliness; in fact, along with the films by Oshima, Wong, and Tsai (see below), the first two are formally the most impressive of the past year, and even The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein concludes with a sequence of convulsive lyricism.

The Circle — a quantum leap for Jafar Panahi after The White Balloon and The Mirror — offers an unprecedented protest against the everyday outrages women have to suffer in Iran that’s at once a gritty noir (focusing on a few women fresh out of prison, as well as a comparably victimized single mother and a defiant prostitute), an expansion of the principles of narrative ellipsis found in the recent work of Abbas Kiarostami (Panahi’s mentor), and a beautifully charted roundelay passing from one woman to the next over the course of a single day. A radical film in every sense, it’s driven mainly by anger and sorrow.

Kiarostami’s more measured ABC Africa, his first film shot on digital video, is about children orphaned by Uganda’s AIDS crisis. The overriding emotions in this case are hope and admiration for people’s resilience in the face of devastation — a theme also found in Kiarostami’s Life and Nothing More (which made a similarly lyrical use of ruins). Completed last spring, ABC Africa turned up at the Chicago International Film Festival, and though it was made in the hope of saving lives, its U.S. distributor, perhaps discouraged by the New York film festival’s rejection of the film, still hasn’t released it. The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein — another key film New York has yet to show, see, or acknowledge — reveals almost equal amounts of anger and detachment. It has much less craft and polish than the other films on this list, but it’s an ambitious effort to capture what the gulf war meant to this country from the vantage point of New Mexico — a theme that’s pursued through three stories and various documentary and experimental segments on everything from war toys to Iraqi music to a Mexican holiday celebration. It can’t be called an entertainment like 1999’s Three Kings, but it’s a complex and passionate human response that seems all the more vital given the recent battering of Afghanistan.

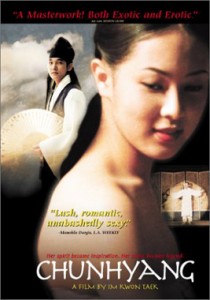

6, 7, and 8: A tie between Taboo and Chunhyang, a tie between Yi Yi and In the Mood for Love, and What Time Is It There?

Many strong Asian films opened here in 2001, but most of the best of them arrived during the first three months. From Japan came Nagisa Oshima’s eerie and beautiful Gohatto (translated somewhat inaccurately as Taboo in the U.S.), which shifted almost imperceptibly over its running time from realism to full-blown expressionism. From Korea came Im Kwon-taek’s lush 18th-century love story and musical Chunhyang, which is simultaneously modernist and traditional. From Hong Kong came Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, which — thanks to its gorgeous and talented leads, Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, as well as its dreamy music — was hands down the most glamorous film of the year, despite (or was it partly because of?) its seedy surroundings. And from Taiwan came Yi Yi, probably Edward Yang’s second-best film (after A Brighter Summer Day, which the Film Center thoughtfully revived) and the first to get any stateside recognition. Last but not least was another masterpiece from Taiwan, Tsai Ming-liang’s best to date, What Time Is It There?, which showed at the Chicago International Film Festival in October and will turn up here in a commercial run later this year. A dazzling two-part invention based on parallel plots in Taipei and Paris and poised between life and death, this tragic comedy has all of Tsai’s usual obsessions (water, alienation, Lee Kang-sheng, certain locations) as well as a Tati-esque scheme of formal rhymes, a mystical notion of cosmic equivalences, and Jean-Pierre Leaud. I’ve seen it only once, but I’d much rather see it a second time than The Royal Tenenbaums or Ali.

9: A tie between Mulholland Drive and Ghost World

These films contain possibly the two most realistic and perceptive depictions of contemporary America in any films this year — the first showing the look and behavior of Hollywood, the second a post-high school teenage limbo. Mulholland Drive, David Lynch’s postsurrealist fever dream, the expansion of a rejected TV pilot, may have set some sort of precedent for being inexplicable yet almost completely satisfying, possibly because Lynch showed some genuine affection for his main characters and some justifiable disdain combined with fascination for where they lived. (I started reading in Salon the impressive efforts of a few critics to decode the incomprehensible bits, then discovered I didn’t much care; the characters and settings with all their multifaceted ambiguities were more than enough.)

Terry Zwigoff and Daniel Clowes’s comic-book adaptation falters and actually goes to pieces by the end, but not before giving us perhaps the best versions of Thora Birch and Steve Buscemi and one of the funniest takes on American art “appreciation” we can ever hope to see.

10: Boesman & Lena

The lovely swan song of the blacklisted expatriate American director John Berry, completed shortly before his death — with Danny Glover, Angela Bassett, and an especially adroit use of wide-screen framing — seems particularly worth noting because it’s already available on DVD.

Here are ten close runners-up, listed alphabetically: Baby Boy (probably John Singleton’s most complex film in terms of feeling and character), Bread and Roses (Ken Loach’s underrated take on Hollywood janitors), Calle 54 (Fernando Trueba’s documentary about Latin jazz), Faat Kine (Ousmane Sembene’s robust tribute to a self-made woman), 15 Minutes (a Hollywood polemic against media excess that sharply divided critics), Kwik Stop (Michael Gilio’s provocatively puzzling first feature, shown at the Chicago festival–see photo above), The Low Down (perhaps the most neglected film that got a local release), The Pledge (the first interesting Sean Penn film), Tape (the year’s second interesting Linklater film, a technical exercise masking a rigorous ethical analysis), and Under the Sand (perhaps the most interesting Francois Ozon film, especially for the performance of Charlotte Rampling).

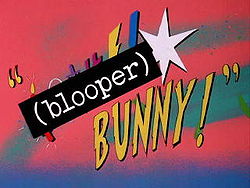

My F.W. Murnau award, which goes annually to films and venues that did the most to enhance my sense of film history, is split between two shorts and a retrospective as well as the venues that presented them, three of our most valuable showcases. The shorts, which offer highly personal takes on film history, are Greg Ford, Terry Lennon, and Ronnie Scheib’s Blooper Bunny (at the Film Center) and Guy Maddin’s The Heart of the World (which opened at the Landmark’s Century Centre). And Facets Multimedia Center, by presenting a comprehensive Amos Gitai retrospective, enabled me finally to catch up with the 1982 Field Diary and its highly pertinent insights about the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, the invasion of Lebanon, and the ways “violence against the Palestinians is ‘legitimized.'” We should all hope our current adventures abroad find a commentator half as astute or as persistent as Gitai.