In the Fray

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Dec 28, 2001 11:37 AM

Dear David, Roger, Sarah, and Tony,

I’m afraid that going to see Monster’s Ball or Black Hawk Down for the purposes of this exchange isn’t even an option for me. Neither has opened yet in Chicago, and though the first and possibly the second got special screenings for local reviewers willing to go beyond Chicago for their 10-best lists, I feel my first duty is to address what Chicagoans can see in my own list for the Reader. In any case, I’m looking forward to seeing Monster’s Ball because of my liking for Billy Bob Thornton and Halle Berry, but the very thought of going to see any war film for pleasure right now gives me the creeps. Though, come to think of it, I’d probably rather see Black Hawk Down than even think again about Audition, one of David’s favorites — a movie whose view of mankind, including audience members, is for me a lot bleaker than anything found in A.I.

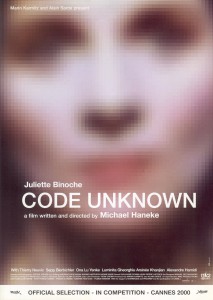

On the other hand, like Roger, I could cite some first-rate movies that exist mainly on television, such as Spike Lee’s A Huey P. Newton Story (which I saw at the Vancouver International Film Festival), even if it’s basically a record of a powerful performance by Roger Guenveur Smith, or Code Unknown, which I saw on the Sundance Channel (where it’s been playing for ages) on Christmas Eve, and which opens here theatrically next week. I think it may be Michael Haneke’s most interesting film — much more important than The Piano Teacher, which swept the awards at Cannes last May, and certainly more challenging as an interactive narrative experiment. On my 10-best list for the Reader, I’ve also cited two features that haven’t yet played in New York — Abbas Kiarostami’s ABC Africa, which has a distributor, and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein, which doesn’t— but turned up at the Chicago International Film Festival. The fact that what we’re mainly discussing represents such a tiny window on what’s going on in cinema —something that’s become even more vast with the spread of digital cinema —effectively means that no one can honestly declare that 2001 was a good or bad year for cinema, because no one on the planet is in a position to know.

On the issue of whether or not In the Bedroom is about vigilantism, I must confess I’m caught somewhere between the first letters of David and Roger. Roger clearly understands the film better than David or me, but I’m with David when he interrogated the wider significance of the film’s meaning — because what a film says isn’t always the same thing as what its maker intends, and what a film is about is what it says and shows, not merely what it defines as its subject. (Roger’s rejection of Iris — another film I haven’t yet seen because it hasn’t come to Chicago, though I share his admiration for Iris Murdoch and John Bayley — is predicated on just such a distinction.) If we assume that vigilantism means taking the law into one’s own hands, regardless of what the perceived motives are—and I do think you’re right, Roger, in your description of those motives—then that’s what Wilkinson does. It’s also what our country often does when it disagrees with international law, and I can’t believe that the importance many people are giving to this film is entirely irrelevant to this parallel; after all, it’s part of the emotional climate we’re living in, and something we’re thinking about daily. It’s also a connection that I think you were very astute in noting, David, in your first letter. I’m not trying to engage either of you on politics—and I’m even willing to accept David’s chastisement for botching my point about Bin Laden. But the ethical issue posed by vengeance strikes me as central to our culture, even without reference to Sept. 11, and if Todd Field regards it as peripheral, I’m afraid he loses me as a consequence.

I can appreciate A.I. losing David for the reasons he states, though I should add that one could reject one of Robert Bresson’s greatest films, Au hasard Balthazar, with a similar argument — if one assumes that the heroes of these films are respectively a robot and a donkey rather than mankind as perceived through the world these characters move through and how they get treated. I looked up your Slate column on the film, David, and I’m afraid I can’t buy your premise about Spielberg and Kubrick’s “shared longing for machines that will deliver humanity from unhappiness.” If anything, A.I. is a cautionary tale against believing any such nonsense and so is the middle section of 2001 (a film, which, I was shocked to hear from Godfrey Cheshire, Warner recently re-released in New York in a 70 mm print with no advertising, apparently due to a contractual agreement that was made with Kubrick when he was still alive).

It seems like the three of us corresponding now are all sold on Ghost World, Mulholland Drive, and Gosford Park — and maybe we can also include Waking Life if we factor in David’s also-rans. Apart from all having very distinctive visual styles, I wonder if they have anything else in common.

Peace,

Jonathan