From the March 25, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

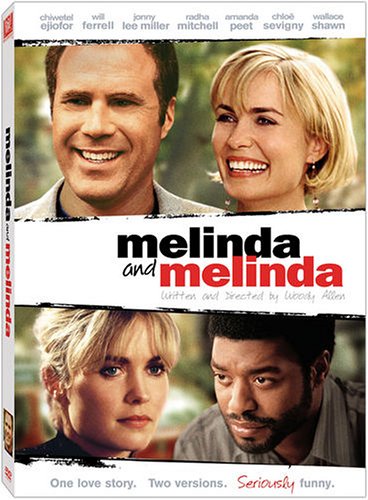

Melinda and Melinda

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Radha Mitchell, Will Ferrell, Chloe Sevigny, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Jonny Lee Miller, Brooke Smith, Wallace Shawn, and Larry Pine

Brainteaser movies have been enjoying a certain vogue in the past few years. The taste for them can be traced back to at least 1994 and the jigsaw-puzzle narrative of Pulp Fiction. But the trend got started in earnest in 2000, with the release of Memento, which tells a complicated story backward, and it gained further momentum two years later when the same gimmick was combined with sex and violence in Irreversible. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Kill Bill have more substantial characters than either of those films, yet part of their appeal lies in the challenge of putting scrambled narrative pieces together.

There are people who say they don’t like to read or write but spend plenty of time doing both on the Internet. Similarly, there are people who say they don’t like to think while watching movies yet don’t mind using their brains when it comes to “puzzle” movies. But there are different kinds of thinking. Figuring out the story in these films takes so much concentration that other issues — what the stories mean, whether they’re worth telling, whether the characters are just disposable genre machinery — become secondary. Ultimately the filmmakers are treating the characters as objects and encouraging viewers to see them the same way. Among current releases, The Jacket seems intended to appeal to the same taste.

As usual, Woody Allen’s latest feature, Melinda and Melinda, has something to do with struggling artists in classy apartments on the Upper East Side and in the West Village — what the New York Times‘s A.O. Scott aptly terms real estate porno. But whether Allen’s conscious of it or not, he’s also pitching to some of the people who like the brainteasers, an impulse that has a much bigger impact than the script’s intellectual, artistic, or pornographic furnishings.

Allen tells the same story in two alternate styles, one “tragic,” the other “comic.” The framing device that justifies this simplistic exercise is an argument between two playwrights in a downtown bistro. Sy (Wallace Shawn) maintains that “the essence of life isn’t tragic, it’s comic,” and Max (Larry Pine) maintains the opposite. When a friend starts telling an allegedly real-life anecdote about a former college chum named Melinda (Radha Mitchell) crashing a dinner party, each of them maintains that the story illustrates his point. The remainder of the film oscillates between a tale of abject misery and a romantic comedy, each featuring Melinda with a different set of characters while following the same basic plot. Eventually, as you might have guessed, the playwrights conclude that comedy and tragedy aren’t as far apart as they assumed.

This sounds like it could work — so long as you don’t think about it too much and you believe that romantic comedy and abject misery are opposite sides of the same coin, as they almost invariably are in Allen’s world. But keeping up with which story was which absorbed most of my attention, and the few times I got a chance to think about what Sy and Max were saying I was disappointed. I couldn’t buy that two supposedly sophisticated theater people could be so simpleminded about what defines comedy and tragedy. I also couldn’t believe in most of the characters, including either version of Melinda. The notable exceptions were black characters played by Chiwetel Ejiofor in the darker story and Daniel Sunjata in the sunnier — it’s refreshing to find black characters of any kind in an Allen film, especially unstereotypical ones.

Allen often uses musical signals to let us know whether what we’re watching is supposed to be funny — lively jazz to signal comedy, and classical music, often modernist, to signal tragedy. His intent is obvious enough when he uses snatches of numbers by Erroll Garner (“The Best Things in Life Are Free,” “Somebody Stole My Gal,” “Will You Still Be Mine?”) or Bela Bartok (String Quartet no. 4), though it’s awfully facile to stick Garner in a box labeled lighthearted and Bartok in one labeled gloomy. Typecasting becomes caricature when Allen moves on to sound bites from Duke Ellington (“Take the ‘A’ Train,” “In a Mellow Tone,” “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart”), Igor Stravinsky (Concerto in D for String Orchestra), and Bach (Partita no. 3, the second prelude from The Well-Tempered Clavier). The musical pieces get shortchanged, and so do we listeners. It doesn’t help that Allen sometimes gives us additional portions of the same works, because he’s still using them as if he were turning a faucet on and off.

He uses many of his actors in a similar way, another indication of the disdain with which he views his audience. A “tragic” act in the darker story can feel as much like a sucker punch as a wisecrack uttered by Will Ferrell (Allen’s latest surrogate) in the lighter story. Allen may be aware that if he gives us time to think about these characters we won’t buy them, so he works overtime keeping us busy with other matters. Ultimately he isn’t interested in engaging our minds with his slender premise, only in entertaining us — and indulging himself in a dubious exercise.