This is the 11th one-page bimonthly column that I published in Cahiers du Cinéma España; it appeared in their March 2009 issue. — J.R.

Tomorrow I start teaching the final semester of a course and film series I’ve been offering at Chicago’s School of the Art Institute devoted to world cinema of the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s. To provide a segue between the Depression of the 30s and the 40s, I’ll be starting with a double feature devoted to economic desperation, Preston Sturges’s Christmas in July (1940) and Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour (1945).

Two of the most popular films I showed last fall were Lubitsch’s The Man I Killed (1932) and McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow (1937). I selected them before last year’s economic recession started, and the congruence and relevance of certain themes — remorse about warfare and spurious patriotism, crowded family apartments and neglect of the elderly — probably added to their appeal. But the contemporary impact of films is always difficult to predict. I’m convinced that a significant part of what inspired Clint Eastwood to make Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima was the U.S. occupation of Iraq, but this relevance wasn’t discussed in the press. In most such cases, a denial of contemporary relevance seems almost obligatory. To cite an extreme example, when Elaine May’s Ishtar (1987) satirized American stupidity in the Middle East, the U.S. media’s almost universal and scornful rejection of this comedy as “terrible” refused to grant the film any political dimension at all.

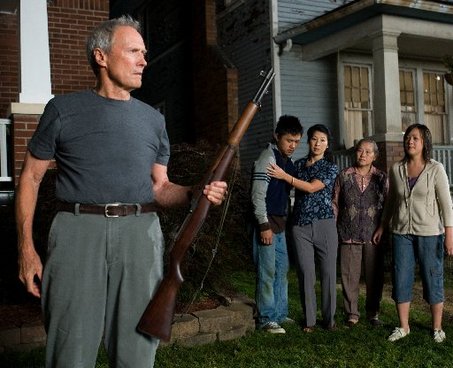

This isn’t the case with Eastwood’s latest feature, Gran Torino — which I’m happy to say has already, seven weeks into its run, grossed almost a hundred million dollars. But it’s worth noting that the website Rotten Tomatoes describes the critical “consensus” as follows: “Though a minor entry in Eastwood’s body of work, Gran Torino is nevertheless a humorous, touching, and intriguing old-school parable.” Why in fact an outspoken and highly critical (and even Fulleresque) treatment of American racism should be deemed “minor” alongside Eastwood’s previous film, Changeling — which deals with such burning contemporary issues as the corruption of the Los Angeles police force in the late 20s — is a sociological question of some interest, but not one I could presume to answer.

At least the American reviews have been right in connecting Eastwood’s hero, Walt Kowalski — an embittered and racist retired auto worker, widower, and Korean war veteran in a Detroit suburb — to his “Dirty” Harry Callahan 37 years ago. Indeed, it’s interesting to reflect that while Don Siegel, the liberal director of Dirty Harry, expressed only pride with the huge commercial success of that rightwing thriller, Eastwood himself, a conservative, has been devoting much of his career in recent years to critiquing his own conservatism from within, with particular attention given to Dirty Harry and all that he has come to represent.

Of course it’s the capacity and privilege of some of the greatest stars to examine the dark side of their own personas (think of the parallel cases of Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux and Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), and it should be added that Eastwood has been explicitly critiquing his own macho bluster as an actor for some time — perhaps most impressively in the underrated White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), where he complicates matters by offering what might be called a Brechtian impersonation of John Huston (that is, a performance in which we’re constantly aware of Eastwood playing Huston) that also becomes a parody of American imperialism, liberalism, and Hollywood entitlement as well as macho posturing. But even though there are gaps in his portrait of Walt Kowalski — we understand practically nothing about his former marriage, for example — the portrayal of his attitudes towards a family belonging to an Asian minority, the Hmong, who move next door to him (and who aren’t in the least bit romanticized) couldn’t be more scathing.