Posted on the Film Comment web site, October 16, 2017. A French translation of this essay by Jean-Luc Mengus has recently been published in Trafic. — J.R.

My late father was never a cinephile, not even remotely, but he managed and programmed a small chain of movie theaters in northwestern Alabama for about a quarter of a century, from the mid-’30s to 1960. And during most or all of that period, he read Time magazine every week, from cover to cover. This means that from September 1942, half a year before I was born, until early November 1948, and not counting all the press books that passed through his office and the various trade journals he subscribed to, just about everything he read and knew about movies came from the so-called Cinema pages of Time, and most of these were written by James Agee.

But he probably had little or no idea who Agee was during this period, even though their stints at Harvard had overlapped, because none of Agee’s writing for Time was signed and my father usually didn’t read The Nation while Agee was concurrently writing his film column there. It’s unlikely that he saw Abraham Lincoln, the Early Years on Omnibus in 1952 because we didn’t have a TV set then, and more probable that he saw The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky in Face to Face the following year at one of his theaters. (Agee wrote and appeared briefly in both of these.) I know that he saw The Quiet One (1948), which Agee wrote, because I remember a 16mm screening of that film at an interracial meeting held in our living room, most likely during the same period. But I suspect he only became fully aware of Agee when the critic entered the American mainstream in 1957, with the posthumous publication of A Death in the Family.

I’ve gone into all this detail because I’m trying to chart what effect Agee’s writing about film in Time might have had on American film taste, and insofar as my father is a pretty good test subject, I’m inclined to conclude that it was minuscule and fairly insignificant. The only enthusiasms for directors that my father fully shared with Agee, as nearly as I can recall, were regarding Laurence Olivier, David Lean, and Carol Reed. Neither The Rules of the Game nor Citizen Kane meant much to him when he saw them, although I recall he did get a rise out of 8 ½.

Over the 539 pages of Time movie coverage gathered in Charles Maland’s costly ($99) 1,037-page collection — Volume 5 of The Works of James Agee published by The University of Tennessee Press — the only time Citizen Kane gets mentioned is a passing allusion to “the Citizen Kane fracas” in Agee’s sometimes gushy extended story about Hollywood gossip columnist “Lolly” (Louella) Parsons. This is because the coverage is (and undoubtedly was) far more valuable as journalism — or what we would now, more precisely and more accurately, call “infotainment,” a rather shameless blend of striking “facts” and jazzy promo for the studios — than as criticism.

It’s certainly welcome to have all or almost all of Agee’s prose about movies for Time in one place — the principal value of this compendium, which also prints or reprints all the Nation reviews and other published film pieces as well as 60-odd pages of “unpublished manuscripts” — but it’s also hard not to regard this as a mixed blessing. The Time writing is frequently arch and/or inflated, far beyond the occasional excesses of Agee’s Nation columns, and even though we find him bending Timespeak here and there to suit his own special gifts — referring to Cab Calloway as a “haberdasher,” or claiming that Charles Bickford in Renoir’s The Woman on the Beach “looks rather like a Beethoven left out in the rain” — he’s far more often punching the clock and grinding out his dutiful hack reports of whatever happens to be around that week. And at times, given the usual requirements of Time’s slangy patter, he can be just as flamboyantly alliterative as Andrew Sarris. (From one of his most entertaining cover stories: “This eminence Columnist [Hedda] Hopper shares (reluctantly) with her rival in revelation, Hearstian Columnist Louella (‘Lollipop’) Parsons, fat, fiftyish, and fatuous, whose syndicated column reaches some 30,000,000 readers.”)

Infotainment is of course far from a worthless activity, and Agee practiced it with uncommon skill, but apart from some periodic overlaps, it shouldn’t be confused with criticism per se. And indeed, it’s partially the overlaps that makes all this Time material a mixed blessing. The fact that the magazine’s prose was anonymous by design also has to be factored into its ambiguous essence (shared today by The Economist, which is far less mannerist in style).

Given the usually overheated writing about forgettable and forgotten subjects, one can agree with Maland — an English professor and Chaplin specialist at the University of Tennessee — that it’s hard to imagine Agee using some of the Time-ese phrases on his own initiative: “To mention just the ones that begin with ‘cine,’ you can find the following in Agee’s Time reviews: cinemactor, cinemactress, cinemacting, cinemaddict, cinemaudiences, cinemantrap, cinemama (actress playing a mother), cinemusicals, cinemoguls and cinemagnates (both for studio heads), cinemug (a face on screen), cinemakeup, cinemadaptations and cinemalteration (both for film adaptation), cinemoans (films that elicit groans), and even cinegenic (photogenic on screen).” It’s small wonder, then, that due to uncertain indexing and attributions, Maland has discovered through more careful research that no less than 13 of the Time pieces ascribed to Agee and included in both Agee on Film (the venerable 1958 edition) and Library of America’s 2005 anthology Film Writing and Selected Journalism, including a couple on quintessentially Ageean subjects (The Gold Rush and D.W. Griffith) are not by Agee at all — and these, appropriately, are omitted from Maland’s collection. (It’s worth adding that Maland admits that some of his own attributions remain less than 100 percent certain, and a few of the pieces are listed as co-authored.)

It’s even smaller wonder that so much of Agee’s independent writing is radically rebellious and unreasonable, in reaction to this form of corporate slavery — from Let Us Now Praise to Famous Men to the original draft of his untitled final novel that was edited into A Death in the Family (available as Volume 1 in The Works of James Agee, and substantially different from the mainstream “classic” that was carved out of it), and including such cantankerous essays as “Pseudo-Folk” (included in Agee on Film, but not in Maland’s collection) and “I’d Rotha Be Right” (which Maland publishes for the first time). In “Pseudo-Folk,” which Partisan Review published in 1944, Agee’s attacks on the Paul Robeson production of Othello and the stage productions of Carmen Jones and Oklahoma is followed by the parenthetical admission that he hasn’t seen them “because I felt sure they would be bad.” His earlier review of Iris Barry’s editing and translation of Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s History of Motion Pictures, quite sensibly rejected by the same journal in 1938, begins with the admission, “I have not read much of the book; nor do I intend to; nor do I think it necessary to in order to indicate that it is not worth the attention of an intelligent reader, that it can only further confuse the confused reader, that it is therefore a thoroughly reprehensible piece of work, and that the translator is ill qualified to hold the important and responsible position she does hold in the Museum of Modern Art Film Library.” His longstanding detestation of Iris Barry — “whom Agee loathed beyond all reason,” according to his biographer Laurence Bergreen — was such that he wrote to Dwight Macdonald, while taking a break from work on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men to draft this hysterical review, about seizing the “beautiful chance to rape Iris Barry, who . . . badly needs it.” (Bergreen, who quotes from this letter, errs in supposing that the Bardèche-Brasillach book was actually written by Barry, but it seems that Agee’s attitude toward her as expressed in this sentence and review makes the mistake understandable. Moreover, one should add that the fact that Brasillach was an anti-Semite who would seven years later be executed for his collaboration with Nazis plays no part in Agee’s indictment, which he wrote far too early to be aware of this.)

All these examples are intemperate refusals of mainstream etiquette and, in most cases, corporate sponsorship, the very thing that supported Agee for most of his life. (This is a form of countereaction that I’ve lived through myself in portions of my own career as a freelancer — probably most starkly in 1979, when I was writing mainstream articles for American Film to subsidize the concurrent writing of my rebellious, experimental, and literary first book, Moving Places, with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men serving as one of my conscious models.) But sometimes this strategy of abrasive opposition can backfire. In his rejected anti-Barry screed, Agee’s assumption of certain givens in film taste are so shockingly dated and ill-considered that they make him sound like a jerk. To Agee, calling Scarface “the masterpiece of gangster films [without] a trace of sentimentality” (as Bardèche and Brasillach do), Charles Laughton a “memorable actor,” and The Docks of New York “von Sternberg at his best” are so clearly signs of idiocy and mental corruption that his own counter-judgments about these matters don’t even need to be spelled out, much less argued. For the record, there are several passing references to Laughton’s acting in Agee’s subsequent Time and Nation reviews, most of them favorable, and his objections to the praise for The Docks of New York are tied to the authors comparing it to Ford’s The Informer, which Agee seems to detest even more—and mitigated somewhat by his concession that Barry “does point out the speciousness of The Docks of New York,” without clarifying what this speciousness consists of, for her or for him. As for Scarface, which is never mentioned again in Agee’s collected works, his principal ire seems to have been provoked by the French authors’ praise for Paul Muni and their mentioning James Cagney only in passing. (“I venture that The Public Enemy, though it is easy to overrate it, is about eight times as good as Scarface and that Cagney’s performance [if there must be ‘performances’ in movies] is not at all easily overrated.”) And he’s only slightly more forthcoming about his detestation of Barry’s passing defense of one of Frank Capra’s most cherished features: “…I would have to add that It Happened One Night, an unusually expert and pleasant and almost perfectly valueless show, is overrated past nausea by that sort of highbrow who has belatedly discovered that it sounds intelligent to say that a pure commercial picture can be good (some of our best friends are commercials)…”

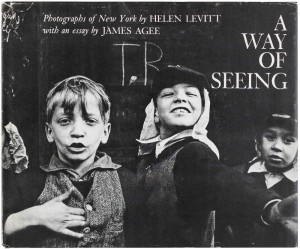

Frankly, the whole piece is an embarrassment, and I can only surmise that Maland opted to include the Barry pan because he thought Agee’s opinions in this case had some legitimacy. On the other hand, Maland clearly omitted “Pseudo-Folk” because that piece has little to do with film directly, but I’m glad that he decided to reprint Agee’s 1946 introduction to A Way of Seeing: Photographs of Helen Levitt (1965), which also has nothing to do with film but happens to be one of Agee’s finest essays, and it was sadly omitted — along with his extraordinary 1943 “America, Look to Your Shame!” — in the Library of America’s 2005 Selected Journalism. Even though the essay refers to the Levitt photographs (which aren’t reproduced here) for much of its meaning — which is one of the reasons why I’ve clung to my copy of the wonderful Levitt book for over half a century — it’s still great to have its prose back in print.

When Manny Farber arranged for his own “complete” film criticism to be published posthumously, he requested that all of his own Time reviews (from mid–August 1949 to mid–January 1950 — a gig arranged for by his pal Agee when he left the magazine) be omitted because of how much they were rewritten. Agee, of course, never had such a choice regarding the reprints of his own work, and considering how much his reputation is based on posthumous biographical and romantic legends about him, the sheer weight of his extended careers at Fortune and Time for most of the 1930s and 1940s is usually skimped. So a comprehensive strategy of inclusion gives a logic to much of Maland’s work, yet I must confess that whereas the Library of America’s Farber on Film enhances and expands Farber’s importance as a critic, Maland’s volume, perhaps unwittingly, diminishes the critical importance of Agee. Maland strains to argue otherwise, such as when he writes, “Agee’s pantheon is significant because in this dimension of his work he was celebrating the work of individual directors and in doing so could be considered an early auteurist, anticipating by nearly a decade the auteur approach that would flower in France in the 1950s and in the United States in the 1960s.” This special pleading is misplaced because the hallmark of what he calls “the auteur approach” on both sides of the Atlantic was the discovery of style as personal expression in studio films, something Agee was blind to when it came to, say, Jacques Tourneur in Out of the Past (or, apparently, in Tourneur’s three remarkable pictures for Val Lewton, none of which Agee reviewed), John Berry in From This Way Forward, Andre De Toth in The Other Love, or Robert Siodmak in The Killers, all of whose names go unmentioned, even if Agee does mention Delmer Daves in his Time reviews of The Red House and Dark Passage (and Berry in his Time review of the far less personal Casbah) and ridicules Michael Curtiz’s liking for camera movement in his Nation review of Casablanca. For all his evocative descriptions of silent slapstick, Jean Vigo, Notorious, and Monsieur Verdoux, Agee’s writing is mostly literary in its language and much of its critical methodology, and far more tuned to gesture, mood, and visual texture than to the stylistic expressiveness examined by critics in the 1950s Cahiers du Cinéma or Sarris in the ’60s. Perhaps for the same reason, he tended to show hostility towards expressionism in most of its forms (Kane, much of Fritz Lang, Jammin’ the Blues, and The Three Caballeros, though not Odd Man Out — one wonders how he might have responded to Laughton’s direction of his own Night of the Hunter script), generally preferring his film fiction in a style closer to that of documentary. Indeed, one of the more intriguing aspects of his first published piece of criticism — a rave notice accorded to Murnau’s The Last Laugh in 1926, when he was a sophomore at Phillips Exeter Academy—is that it shows more enthusiasm for expressionism and subjective camera (“we see distorted faces of fiends glaring at us, laughing hideously”) than we generally find in his adult writing, and this winds up being the only Murnau film that’s ever mentioned in this hefty volume. (Lang fares only slightly better.)

Given how many forgettable ’40s films Agee bothered to write about, it’s remarkable how many stylistically memorable films of that era he missed or at least never reviewed, such as Laura, Beauty and the Beast, Duel in the Sun, The Lady from Shanghai, and Letter from an Unknown Woman, or else conspicuously undervalued — another honor roll, stretching from Maya Deren to Good Sam. (Maland alludes to Agee’s “review” of Duel in the Sun, but in fact it’s only a brief, opinionated news story about Selznick’s censorship battles.) And of course the greatest difference between Agee and Farber in terms of contemporary significance is the fact that Agee unlike Farber didn’t live long enough to confront any Asian or African or Middle Eastern films or anything by Akerman, Antonioni, Bergman, Bresson, Fellini, Godard, Resnais, Tati, Truffaut, or Varda. Perhaps the closest Agee ever got to 1960s film culture was reviewing Sjoberg’s Torment, which boasts an early Bergman script. So he clearly belongs to a separate era of film culture that more or less ended with the early years of Italian Neorealism, prior to The Bicycle Thief, Umberto D, and the Rossellini-Bergman films. This alone sadly places him closer generationally to Bosley Crowther (born four years earlier) than to Farber (born eight years later).

***

Apart from the lamentable “I’d Rotha Be Right,” the other “Unpublished Manuscripts” selected by Maland range from the mildly interesting to the mildly uninteresting while continuing to show Agee as being handicapped by living in what might be called the prehistory of film history. The section “Movie Digest” includes over two dozen capsule reviews of films from the mid-1930s, stylistically similar (though mostly inferior) to reviews of this kind that he would write for the Nation in the 1940s, with few surprises (apart from the assigning of letter grades to many of the reviews), generally suggesting some early trial runs at movie reviewing. “Unpublished Column on René Clair,” probably written in 1944, is also unsurprising and unexceptional apart from some characteristically Ageean hair-splitting. A letter of suggested film titles for the Library of Congress with comments to Archibald MacLeish, never intended for publication, is both repetitious in its own right and redundant in (mostly) restating the critical positions of his published work, and the same could be said for “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for a Museum of Modern Art Roundtable,” “Notes for Article on American Movies for Special Issue of Horizon on American Art,” and two proposals for pieces about Eisenstein that he never wrote, one for Time and the other for the Nation.

But the historical innocence of Agee revealed in the Eisenstein proposals is worth noting. Though it’s fully understandable that he would view the first part of Ivan the Terrible as unambiguous Stalinist propaganda, the more recent and exceptional scholarship of Yuri Tsivian and Joan Neuberger have shown both parts to be courageous acts of bravado and even in some respects defiance. I assume it’s merely an oversight that led him to state in his proposal (circa 1947) for a Time cover story on Eisenstein that in contrast to the latter’s troubled career after Que Viva Mexico, “another Russian [sic] director of very great ability, Alexander Dovzhenko, has not, thus far, gotten into any trouble.” (Strangely enough, Maland in a footnote also identifies Dovzhenko as Russian.) That this writer could have been so shockingly ignorant about one of his most cherished filmmakers — an anti-Russian Ukrainian partisan who spent virtually his entire life under Russian surveillance, and whose conflicts with the Russian government were already substantial at least as far back as the 1930s—only goes to show what a historical divide separates us now from Agee on matters of film history. To assume that his considerable literary talent can make up the difference may, alas, be only wishful thinking.