Film history that is open to the present

Posted By Jonathan Rosenbaum on 11.14.06 at 04:07 PM

Last month Alexander Horwath, director of the Austrian Film Museum, sent me a press release about an ambitious and audacious retrospective he’s presenting throughout November entitled “Notre Musique,” devoted to “forty major works of fictional and documentary cinema made between 2000 and 2006.” “Film museums are often — and justifiably — viewed as places where an awareness of the historic foundations of contemporary cinema can evolve,” he begins. “Yet a reverse perspective is equally important — an approach to film history that is open to the present.” His selection, he adds, “is not so much influenced by the best-known or `most-discussed’ films of recent years but rather by the unbroken capacity of cinema to bear witness to life on this planet [his emphasis] — not just in the sense of documentation but also as an illumination of circumstances that habor a potential for change.” What he’s put together, in short, is a group of films that are supposed to bear witness, politically and responsibly, to the present moment — a daring gesture if one considers Jacques Rivette’s plausible statement in a Cahiers du Cinéma roundtable over 40 years ago, that it’s virtually impossible for a critic to know the long-term value of a film when it first appears. As critics, of course, we’re all expected to assume the contrary, but let’s get real: none of us can predict the future well enough to know the perspectives and priorities of subsequent generations.

I’ve seen a little less than half of Horwath’s selections, but based on the titles I know — which include such films as Yi Yi, Mysterious Object at Noon, Nobody Knows, Moolaadé, The World, and La Ciénaga — it seems overall like a reasonable and intelligent list. Yet one of the three American titles selected, The Royal Tenenbaums, sticks in my craw, raising the question of how much any American film history of the present is likely to be composed differently inside and outside America. Horwath’s other two American selections, An Injury to One and Land of the Dead, strike me as irreproachable, both of them admirably bearing witness to what’s been happening in this country lately — even though the first of these, an experimental documentary by Travis Wilkerson, is about the murder of a radical union organizer in 1917. (As Fred Camper wrote in the Reader, Wilkerson “uses stark Montana vistas, combined with titles and narration, to argue that the depredations of capitalism lie behind every ruined landscape,” which is contemporary enough for me.) But The Royal Tenenbaums as some sort of index to what’s happening in the U.S. circa 2001? It’s not a matter of dissing or trashing Wes Anderson’s comedy to say that even from its pie-eyed middle-class perspective, it has little to offer on this subject — or at least little that I can see. But maybe Alex sees something in it that I don’t and should.

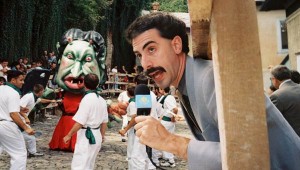

In any case, despite this demurral, I’m grateful for the way Horwath reminds us critics that we should try to look at current films through what might be described as historical bifocals — that is, try to imagine what they’ll look like from the distance of a few years as well as what they currently look like from close range. From this standpoint, two recent releases, Flags of Our Fathers and Borat, both of them too recent to have made it into his list, strike me as being exemplary snapshots of how and where this country stands at the moment, especially in relation to a certain kind of self-hatred. The first of these seems to me a noble failure, commercially as well as artistically, but still a valuable indication of how unhappy many Americans currently are with the war in Iraq. And the second testifies to American self-hatred even more — though some of this hides behind an alleged mockery of Kazakhstan, a country most Americans know little and care less about.