From the Chicago Reader (March 11, 1994). — J.R.

*** THE SCENT OF GREEN PAPAYA

(A must-see)

Directed and written by Tran Anh Hung

With Lu Man San, Tran Nu Yen-khe, Truong Thi Loc, Nguyen Anh Hoa, Vuong Hoa Hoi, and Tran Ngoc Trung.

Until fairly recently, films from the Chinese- and Vietnamese-speaking world have had next to no distribution here; so it’s worth noting that three such movies have been nominated for the foreign-language Oscar: Farewell My Concubine from Hong Kong, The Wedding Banquet from Taiwan, and The Scent of Green Papaya from Vietnam. The first two of these have already opened in Chicago, and the third — in some ways my favorite in the bunch — is starting a run this week at the Fine Arts. What overlapping interests — economic, cultural, artistic, ideological — are being served by this sudden upsurge in attention?

Interestingly enough, none of these Oscar nominees qualifies purely and unambiguously as a movie representing the country officially attached to it. Though Farewell My Concubine was produced in Hong Kong, all its action takes place in mainland China, and it was directed by a celebrated “Fifth Generation” filmmaker, Chen Kaige. The Wedding Banquet, a Taiwanese-American coproduction, has a Taiwanese director, Ang Lee, but it’s set in New York City and much of its dialogue is in English. Read more

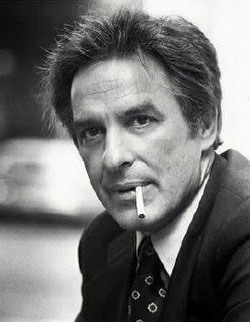

In memory of Dušan Makavejev (1932-2019). Commissioned and originally published by Criterion for their DVD of WR: Mysteries of the Organism in 2007. I was occasionally reminded of this film while recently watching Radu Jude’s no less brilliant and equally singular time capsule of 2021, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn.— J.R.

Between the mid-1960s and the mid-1970s, it was generally felt among Western intellectuals and cinephiles that cutting-edge, revolutionary cinema came from Western Europe, Latin America, and the United States. Among the touchstones were Jean-Luc Godard’s films in France, Newsreel’s agitprop documentaries and their spin-offs (like Robert Kramer’s Ice and Milestones) in the United States, such diverse provocations as Lindsay Anderson’s If…. and Godard’s 1+1 in the United Kingdom, and, in Latin America, films like Lucía (Cuba), The Hour of the Furnaces (Argentina), and Antonio das Mortes (Brazil).

By contrast, the wilder politicized art movies coming out of Eastern Europe at the time — such as those of Vera Chytilová, Miklós Jancsó, and Dušan Makavejev — were treated as curiosities, aberrations that wound up getting marginalized by default. The fact that they came from Communist countries made them much harder for Westerners to place, process, and understand; in most cases, an adequate sense of context was lacking. Read more

Written in October 2012 for what was supposed to have been the first (and, so far, only) translated edition of my most recent collection, although it has never come out. There is, however, a Korean translation of my earlier collection Essential Cinema (with a new Afterword, available here).

In retrospect, I’m sorry that I didn’t find some way of mentioning Lee Chang-dong’s extraordinary Poetry (2010), my favorite Korean film [see all the stills below] — and one that, incidentally, helps to explain the reason for my alienation from most of the other South Korean films I’ve seen and their excessive reliance on rape and serial killers as subjects (something that I was embarrassed to bring up in this Preface, written at the request of the publisher). This film in fact addresses the theme of rape and its role in Korean society quite directly. — J.R.

My acquaintance with cinephilia in South Korea is limited. My only first- hand knowledge comes from my experience as a juror on Indie Vision at the Jeonju International Film Festival in the Spring of 2006 and my acquaintance over a longer period with the brilliant and discerning critic and programmer Un-Seong Yoo, who worked for that festival for many years and, more recently, was my fellow juror on the New Directors jury at the San Sebastian Film Festival in the Fall of 2011. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 16, 2004). — J.R.

Silver City

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and Written by John Sayles

With Danny Huston, Maria Bello, Chris Cooper, Richard Dreyfuss, Daryl Hannah, James Gammon, Kris Kristofferson, Tim Roth, Mary Kay Place, Billy Zane, Sal Lopez, Ralph Waite, Miguel Ferrer, and Michael Murphy

Almost 60 years ago, in the essay “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell made observations about bad writing that have lost none of their relevance. “As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house,” he wrote. “The attraction of this way of writing is that it is easy. It is easier — even quicker, once you have the habit — to say In my opinion it is a not unjustifiable assumption that than to say I think.”

Ready-made phrases in the news — “smoking gun,” “weapons of mass destruction,” “war on terror” — tend to hurry listeners or readers along instead of encouraging them to think. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 21, 1997). — J.R.

CRASH

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by David Cronenberg

With James Spader, Deborah Kara Unger, Holly Hunter, Elias Koteas, Rosanna Arquette, Peter MacNeill, Yolanda Julian, and Cheryl Swarts.

“Throughout Crash I have used the car not only as a sexual image, but as a total metaphor for man’s life in today’s society. As such the novel has a political role quite apart from its sexual content, but I would still like to think that Crash is the first pornographic novel based on technology. In a sense, pornography is the most political form of fiction, dealing with how we use and exploit each other in the most urgent and ruthless way.

“Needless to say, the ultimate role of Crash is cautionary, a warning against that brutal, erotic and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margins of the technological landscape.”

These are the last two paragraphs of J.G. Ballard’s introduction to his 1973 novel Crash. They point to a seeming paradox that lies at the heart of David Cronenberg’s masterful film adaptation as well as the original — the idea that pornography, by virtue of being political, can play a cautionary role rather than, or in addition to, a prescriptive one. Read more

An expanded edition of my book with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, Abbas Kiarostami (University of Illinois Press, 2004), was published in Argentina by Los Rios, translated into Spanish by Luciana Borrini and Julián Aubrit. (A stil more expanded edition appeared in English much later, in 2018.) One of the two texts added to the Argentinian edition, my essay “Watching Kiarostami Films at Home,” is already available on this site, as are an essay about Shirin I wrote for the Cinema Guild DVD and an earlier dialogue I had with Mehrnaz about the film. Here is the other addition, written by Mehrnaz expressly for the expanded edition. — J.R.

Reflections on Like Someone in Love (2012)

By Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa

I

A phone conversation between Chicago (Saeed-Vafa) and Rome (Kiarostami), March 17, 2013:

MS: When you talked about Shirin in one of your interviews, you said that it was a unique film that could have changed your career, if you had made it earlier. What did you mean by that?

AK: I wished I had made Shirin earlier to get a better emotional understanding of women. Shirin was like a silent, wordless interview with 117 women. You could tell that they were all thinking silently about their private relationships, and we could see their emotions in their faces. Read more

From the March 1986 Video Times. — J.R.

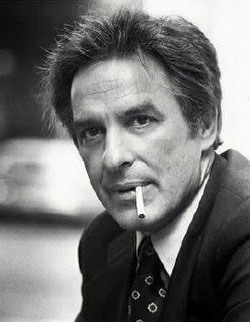

(1984), C, Director: Volker Schlöndorff. With Jeremy Irons, Ornella Muti, Alain Delon, Fanny Ardant, and Marie-Christine Barrault. 110 min. Subtitled. Cinematheque (Media). $59.95.

They said it couldn’t be done, and strictly speaking, it hasn’t been. Proust is ultimately as unfilmable a writer as they come, and any attempt to translate his work to the screen has to be a chancy undertaking. But if we approach Swann in Love as variations on a theme by Proust — a work in its own right, and not an effort to translate the untranslatable — then director Volker Schlöndorff’s elegant film emerges as much finer than critics have admitted.

Clearly, any work as labyrinthine as Remembrance of Things Past — or even Swann in Love, the lengthy, self-contained section of the first volume on which this film concentrates — has to be drastically simplified and formally revamped in order to fit within the borders of a feature film. The solution adopted is to focus almost exclusively on the events of a single pivotal day in the plot. Charles Swann (Jeremy Irons). a wealthy Jewish art critic of 19th-century Paris who moves in aristocratic circles, discovers over this day that his infatuation with the courtesan Odette de Crécy (Ornella Muti) has grown into a jealous obsession. Read more

Commissioned by Criterion’s The Current, and published there on October 26, 2010. — J.R.

For many decades now, William Faulkner’s Light in August (1932) and Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964) have been major touchstones for me—not only separately but also in some mysterious relation to each other. I even managed to find a way of discussing these two works together over the first four paragraphs of my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (I also published a lengthy essay about Gertrud, in which I make glancing reference to the novel). The fact that Dreyer once expressed some interest in adapting Faulkner’s Light in August — an interest he shared with Luis Buñuel (and with actors Zachary Scott and Ruth Ford, a couple who once actually held the film rights) — was part of the inspiration and pretext for my musings about Dreyer and Faulkner, but for me the affinities run much deeper.

Both are works I take pleasure in revisiting every few years — they seem to grow in density each time — and I had occasion to revisit both of them this fall. I’m presently teaching film at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, and last month, after starting a weekly cine-club there with a colleague, we hit upon the idea of showing Gertrud as our first film after another colleague, filmmaker Rob Tregenza, said he’d always wanted to see it. Read more

Note: Unlike some of my colleagues, when I say “available,” I mean in this case available on region-2 discs that can be played on multiregional players, which are easy and inexpensive to come by.

By the Law aka Dura Lex (Po kanonu), directed by Lev Kuleshov 1926 from a script by Viktor Shklovsky that’s adapted from a Jack London’s story (“The Unexpected”), packaged with an 18-minute fragment of Kulshov’s 1927 Your Acquaintance and a bilingual, illustrated 16-page booklet, is available from www.edition-filmmuseum.com for a little under 20 Euros via PayPal.

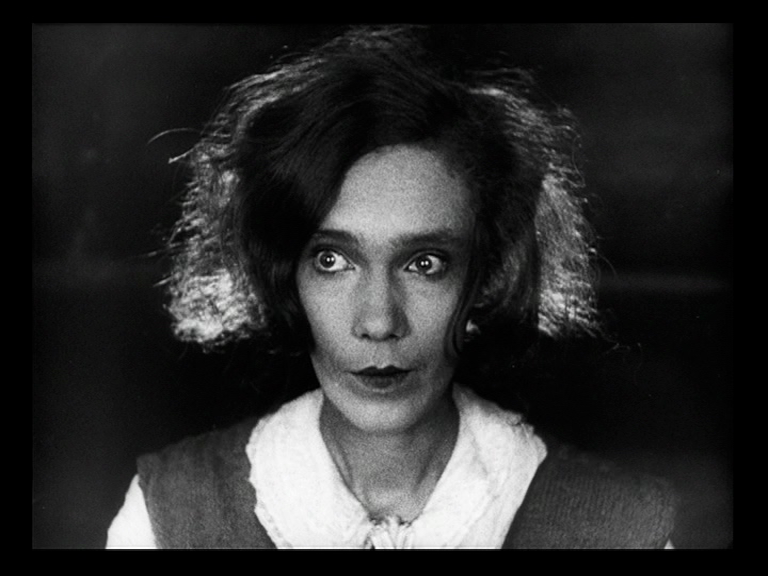

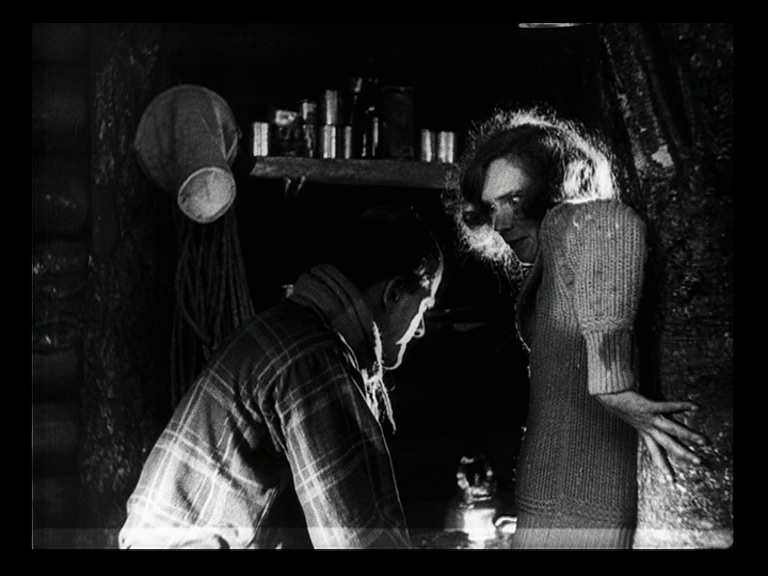

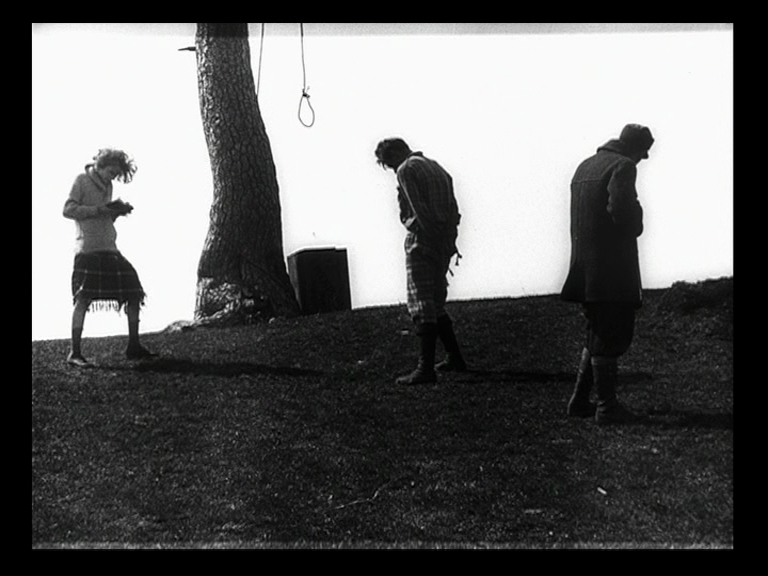

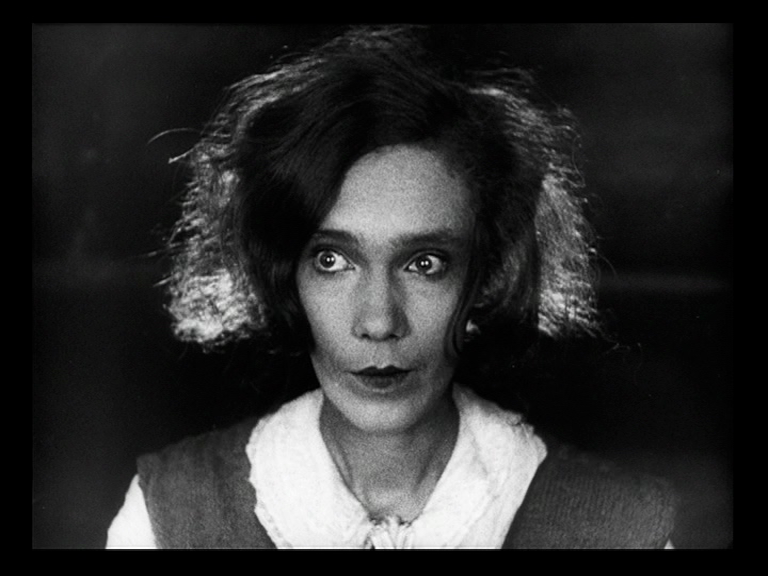

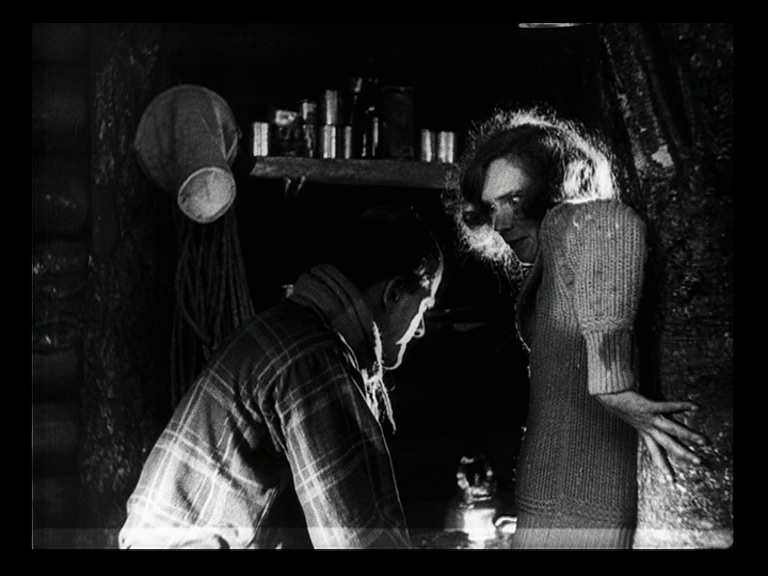

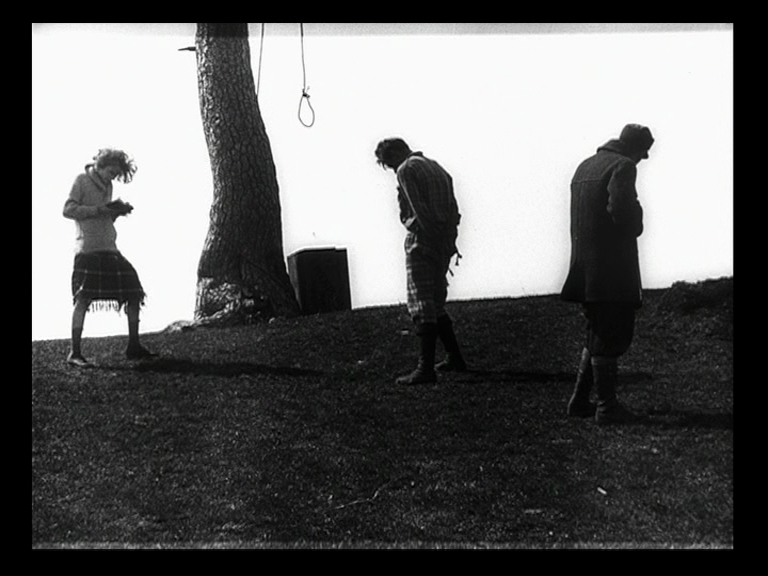

The other two DVDs are of Alexander Dozhenko’s first two masterpieces, Zvenigora (1928), seen above, and Arsenal (1929), seen below. (In both cases, as in By the Law, these frame-grabs come from my own reviewer copies, and were selected almost at random.) The two Dovzhenkos are currently available from an English company, Mr. Bongo that previously released an excellent version of Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930), the final feature in what is sometimes called his silent war trilogy, which my west coast colleague Doug Cummings was kind enough to alert me to. From February 14, when Zvenigora and Arsenal are being released, English Amazon is offering each for just under 8 pounds (a little under $13), an incredible bargain. Read more

From The Soho News, July 18, 1980. Also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995). — J.R.

John Cassavetes, Filmmaker and Actor Museum of Modern Art, 20 June — 11 July

Nineteen years ago, when I was a high school senior making one of those boring, difficult adolescent transitions — from being a social outcast in my hometown in the Deep South to being a social outcast as a southerner at a New England prep school — I had the good fortune to discover John Cassavetes’s SHADOWS at the New Embassy at Broadway and 46th. It was near the beginning of my spring vacation, which meant that I could return to this movie again and again, during the same week or so when I was getting my first looks at BREATHLESS, THE RULES OF THE GAME, ROOM AT THE TOP, SPARTACUS, THE MISFITS, and TAKE A GIANT STEP.

Art in our time, Harold Rosenberg once wrote, appeals either to other artists or “to introverted adolescents, to people in crises of metamorphosis, a small-town girl who has met an intellectual, a husband forced to give up drinking, a business man who feels spiritually falsified, all these being, like the audience of artists, more attentive to themselves than to the work.” Read more

Written in 2010 for the Cinema Guild’s DVD release of Shirin. — J.R.

It doesn’t do justice to Shirin to call it the most conceptual of Abbas Kiarostami’s films. But it probably wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call it the most paradoxical. Not the least of its paradoxes is the way that it simultaneously confronts and defies the specter of commercial cinema, qualifying at once as his most traditional feature and his most experimental. By focusing almost exclusively on the fiction of women watching a commercial feature that we can hear but never see — a feature that in fact doesn’t exist, apart from its manufactured soundtrack — one might even say that Kiarostami, an experimental, non-commercial filmmaker par excellence, is perversely granting the wish of fans and friends who have been urging him for years to make a more “accessible” film with a coherent plot, a conventional music score, and well-known actors.

What’s perverse about this is that the plot in question, while drawing from a traditional epic, a medieval romance widely known in Iran, belongs to an unseen and imaginary film whose on-screen spectators are precisely those well-known actors. (Both men and women comprise this imaginary audience of 110 individuals, although the only viewers featured in close-ups are women.) Read more

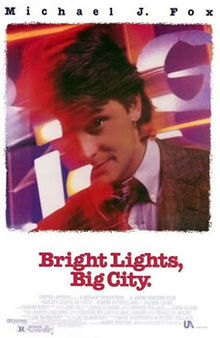

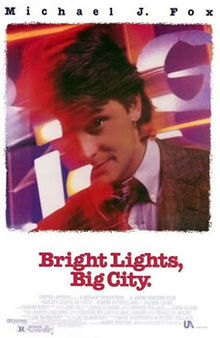

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). — J.R.

BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by James Bridges

Written by Jay McInerney

With Michael J. Fox, Kiefer Sutherland, Swoosie Kurtz, Phoebe Cates, Frances Sternhagen, Tracy Pollan, Jason Robards, John Houseman, Dianne Wiest, and William Hickey.

Considering the thinness of Jay McInerney’s 1984 best-seller, one might imagine that the movie version would stretch out the material, or at least fill in some of the blanks. But by and large, the original text is treated as if it were engraved in marble, and I doubt its fans will have any cause for complaint.

If Melville, Twain, Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Algren, Updike, and Styron have never received a tenth of the respect from Hollywood accorded here to Jay McInerney, this may be because, unlike McInerney, they are writers whose styles and formal structures are easily lost in translation. McInerney’s book, written in the present tense and in the second person, is already aiming for the immediacy and easy identification available from a movie, so most of the work of the filmmakers in putting it across is relatively sweat-free. In fact, given the charisma of Michael J. Fox and the spit and polish of director James Bridges — not to mention the music of Donald Fagen (of Steely Dan) and the cinematography of Gordon Willis — it could easily be argued that the movie fulfills the novel’s designs better than the novel does. Read more

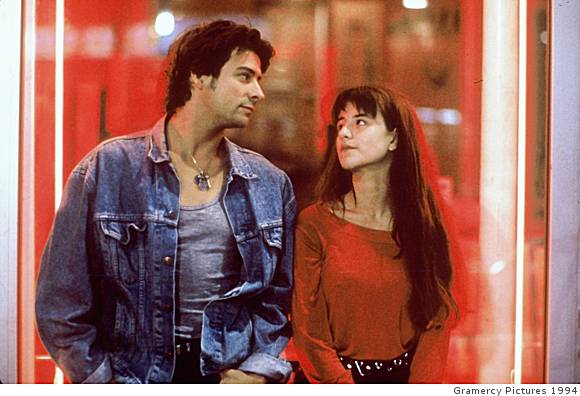

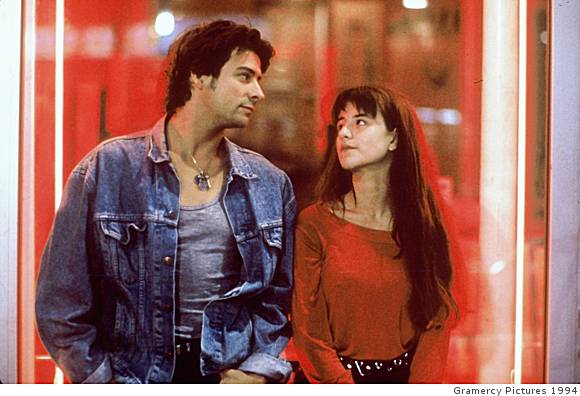

From the Chicago Reader (March 25, 1994). — J.R.

*** SAVAGE NIGHTS

Directed by Cyril Collard

Written by Collard and Jacques Fieschi

With Collard, Romane Bohringer, Carlos Lopez, Corine Blue, Claude Winter, Denis D’Archangelo, and Jean-Jacques Jauffret.

If memory serves, the first time I ever heard of Sylvia Plath was the first time a lot of other people heard of her — in the mid-60s, a few years after she committed suicide, when her posthumous collection Ariel was published. I recall a teacher of mine in graduate school remarking that Plath’s suicide validated her late poetry, implying that if she hadn’t actually taken her own life, poems such as “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy” wouldn’t have meant as much as they did — indeed, may not even have been “as good.”

The remark offended me at the time, but in retrospect I wonder if in some awful, seldom-acknowledged way my teacher was right. Many of us prefer to believe that works of art should be self-justifying, and therefore demand to be taken on their own terms, without “outside” information, but the fact remains that the hyperactive media and life itself rarely offer us that luxury. Take, for instance, these two consecutive stanzas in “Lady Lazarus” — “Dying / Is an art, like everything else. Read more

From the October 2010 Sight and Sound. I regret a few errors that crept into this piece as originally published, all of which were my own fault and all of which are corrected here. — J.R.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention at the outset that Françoise Romand has been a good friend for over two decades. But I hasten to add that she became a friend because of my immoderate enthusiasm for Mix-Up (1985), her first film — one of the strangest as well as strongest documentaries that I know.

To make matters even more mixed-up, I should also point out that, on the region-free DVD bonus of this hour-long French documentary in English, Françoise, after interviewing herself in French, shows her filming of my talking head in English while I attempt to explain why I find her film so powerful and exciting. What follows represents another try.

Filmed over just twelve days, but recounting a multilayered real-life story that covers nearly half a century, Mix-Up recounts and explores what ensued after two English women, Margaret Wheeler and Blanche Rylatt, respectively upper-middle-class and working-class, gave birth to daughters in November 1936 in a Nottingham nursing home, and the babies were inadvertently switched. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 26, 2005). — J.R.

9 Songs

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Michael Winterbottom

With Kieran O’Brien and Margo Stilley

Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll used to be a commercially surefire package that today seems less automatically reliable. Which is presumably why Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs arrives in Chicago 15 months after its Cannes premiere — during the dog days of summer, when art-house films that distributors aren’t quite sure what to do with tend to surface. Sex is the main course, the side dishes are nine concert performances given by rock bands, and the spices are a few glancing references to cocaine and prescription drugs.

Even though it has few of the narrative elements we usually expect, this 69-minute movie is surprisingly fresh and original. The mise en scene, the editing (by Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross), and the camerawork by Marcel Zyskind keep it lively and attractive. The lighting is often exquisite, and the actors sometimes seem like inspired jazz players.

9 Songs is intermittently arousing, but though the sex is real, it isn’t really porn. Jonathan Romney offers a pretty precise description in the London Independent: “Essentially, 9 Songs bets us that it can make sex stand for all the other things that routinely convey character.” Read more