If memory serves, this essay, which first appeared in the Winter 1985/86 issue of Sight and Sound, and was later reprinted in Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995), took me at least a year to write — and maybe even longer than that — because of all the research it required. I’ve recently revised the title slightly from “GERTRUD as Nonnarrative” to “Gertrud as Nonnarrative” because my basic argument concerns the character Gertrud rather than the film as a whole. — J.R.

There are narrative and nonnarrative ways of summing up a life or conjuring a work of art, but when it comes to analyzing life or art in dramatic terms, it is usually the narrative method that wins hands down. Our news, fiction, and daily conversations all tend to take a story form, and our reflexes define that form as consecutive and causal — a chain of events moving in the direction of an inquiry, the solution of a riddle. Faced with a succession of film frames, our desire to impose a narrative is usually so strong that only the most ruthless and delicate of strategies can allow us to perceive anything else.

Carl Dreyer allows us to perceive something else, but never without a battle. The nonnarrative specter that haunts the narrative of GERTRUD (1964), contained in the figure of Gertrud herself, is threatened at every turn by dogs snapping at her heels — a narrative world of men with pasts and futures who stake a claim on her. But Gertrud, who lives only in a continuous present, persistent and changeless, eludes them all. And if she eludes us as well, this may be because our narrative equipment can read her only as a monotone — an arrested moment (as in painting) or a suspended moment (as in music) that can lead to no higher logic. Yet from the vantage point of her refusal to inquire, she has a lot to say to the men.

To arrive at the nonnarrative side of GERTRUD — the static essentials that no amount of narrative tide can wash away — it is useful to consider the life and art of Dreyer as well. We can begin, in fact, with the stories of two men and four women — Dreyer, Hjalmar Söderberg, Josephine Nilsson, Marie Dreyer, Maria von Platen, and Gertrud — only one of whom is fictional. Starting with these family plots, we can, I hope, reach those aspects of the film which eschew plot altogether.

GERTRUD as Family Plot

1889: Josephine Bernhardine Nilsson, thirty-three, pregnant, unmarried, and Swedish, who manages the household of a large farm in Carlsro, arrives in Copenhagen in mid-January. A couple of weeks later, she gives birth to a son. After the baby is passed from one foster home to another for the better part of a year, and spends a few weeks in an orphanage, Josephine returns to Copenhagen and places an ad in a newspaper claiming that the boy’s father has left for America and looking to get him adopted. Eventually the boy is taken in by a tram conductor and his wife. But when the Petersen family decides not to keep him, Josephine makes a third trip to Copenhagen in late August 1890, places another ad, and finally gets the boy adopted by a typesetter and his wife named Carl and Marie Dreyer, signing the necessary papers two months later. By this time, however, she has found herself pregnant again, perhaps by another man. In her seventh month, mid-January 1891, she desperately attempts to abort the child by taking a box and a half of matches, cutting off the heads and swallowing them, and suffers a hideous death from sulfur poisoning. A macabre autopsy is conducted in Stockholm by a team of doctors, and when it is finally concluded that her death was not suicide, she is buried in a churchyard.

The adopted son of Carl and Marie, named after his adoptive father, has a nonreligious upbringing. His older sister, Valbörg, was also born out of wedlock, when Marie was a teenager and before she met Carl, and throughout the younger Carl’s childhood, Marie expresses her contempt for Josephine having abandoned her child. The boy grows up lonely, taciturn, and resentful; as he was to express it in a brief and rare autobiographical sketch written in the 1940s, he was adopted by a family who reminded him on every occasion that he should be aware of the nourishment he was receiving, and that, strictly speaking, he had no right to anything because his mother had deprived them of her support for him by arranging to die. (When Marie Dreyer herself dies, aged seventy-three, in 1937, he refuses to attend her funeral, saying she has already long been dead for him; he doesn’t even want to hear her name spoken.)

He reveres and idealizes the image of his real mother, however, regarding her as a victim rather than a villainess. In 1908, shortly after his nineteenth birthday, he quits his post at the Great Northern Telegraph Company, leaves Denmark for the first time, and travels to Sweden to learn whatever he can about her. When he returns to Copenhagen three months later, he embarks on a career as a journalist.

1901: Maria von Platen, thirty-one, Swedish opera singer — who at nineteen had married a state official twenty-six years her senior, and who subsequently left him to join a bohemian milieu of artists in Stockholm — writes to the author Hjalmar Söderberg, expressing admiration for his work. A stormy affair develops between them and lasts for many years. Söderberg is tied by an unhappy marriage to an ailing wife; but when he finally succeeds in dissolving the marriage in the spring of 1906, he discovers that Maria has just been seduced by a young writer, Gustav Hellström, and has fallen in love with him. At a party, Söderberg hears Hellström bragging about his recent sexual exploits, Maria yon Platen among them. Enraged and grief-stricken, Söderberg leaves Stockholm for Copenhagen and in the space of a month writes a play, largely based on this experience, entitled Gertrud.

1962: In the newspaper Politiken, Carl Dreyer, seventy-three — who has not made a feature in a decade, and who has been trying to finance one about Jesus for at least fifteen years — reads an article about a doctoral thesis published in Sweden which demonstrates that Söderberg’s Gertrud was largely autobiographical. Back in the 1920s, Dreyer had thought of adapting Gertrud as well as Söderberg’s novel Dr. Glas. Now his interest is sparked in particular by the information that Maria yon Platen had grown up and spent both the first years of her marriage and the last years of her life in the same area where Josephine Nilsson lived. All at once, Dreyer hits on the notion of adding an epilogue to GERTRUD based on von Platen’s last years, to be filmed on location at the very house where she lived — only ten miles from Carlsro, the site of his own conception.

After Dreyer finds a producer for the film, he contacts the present owners of Maria yon Platen’s house, pays them a visit, and writes to her family for permission to shoot there. But too many complications intervene and, as with his desire to shoot GERTRUD in color, he has to set this dream aside, finally agreeing to reconstruct some of the interiors in a studio.

The three narratives above are selectively paraphrased, after a fashion, from portions of Maurice Drouzy’s Carl Th. Dreyer né Nilsson (Éditions du Cerf, 1982), the first Dreyer biography in any language. Collectively, they weave an intriguing mesh of motivations in relation to the cantankerous beauty and contradictory impact of Dreyer’s late masterpiece and most controversial work — most of which is set in 1906, the year he left home. Seizing upon Dreyer’s traumatic relationships to both his real and adoptive mothers as the key that unlocks the mysteries of his films, Drouzy writes a troubled biography that in many respects seems comparable to Donald Spoto’s recent life of Hitchcock. And if his thesis is too monolithic to qualify as a convincing critical argument, it brings a flurry of fresh insights into many corners of Dreyer’s life and work. At the least, it definitively lays to rest some of the misinformation found in most standard works (for example, Katz’s Film Encyclopedia: “He was brought up by a strict Lutheran family . . . “).

An intensely private filmmaker whose scripts were nearly all adaptations, Dreyer has never been regarded as an autobiographical artist, but the obsessional nature of his work has posed mysteries that critics have been trying to unravel for over half a century. (The assumption that Dreyer was a religious artist — suggested by his frequent recourse to religious subjects, but contradicted by virtually all the other information we have about him — is probably the most common method of filling in the blanks.) Without conclusively solving any of these mysteries, Drouzy allows us to speculate further about a good many matters: the persistent images of tortured and/or suffering women (in LEAVES FROM SATAN’S BOOK, MASTER OF THE HOUSE, PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC, VAMPYR, DAY OF WRATH, ORDET); the subject of Dreyer’s first documentary (unwed mothers); the mistrust and lack of identification with all institutions, coupled with the theme of intolerance; his interest in adapting Light in August (which juxtaposes an ideal earth mother with a doomed, illegitimate orphan who can never know his true identity); his passionate feminism; and a great deal more. For Drouzy, much of Dreyer’s oeuvre reflects his attitudes toward his “true” and “false” mothers, and even some of the character names in his films are telling. Only Gertrud encompasses both the true and false mothers by figuring at once as monster and martyr — an intransigent purist like Dreyer himself.

Significantly, Dreyer acknowledged both aspects of Gertrud’s character in various interviews, seeing her as stronger than all the male characters yet intolerant as well (“She can’t accept anything that she doesn’t feel herself”), adding that none of the men could possibly live up to her ideal. One could argue, in fact, that the entire tragic force of the film can be felt behind Dreyer’s passionate ambivalence. Critics on the whole have been divided between regarding her as monstrous or sublime, fulfilled or self-deluded, victim or victor, but the film’s curious achievement is to make her all these things at once, at every moment.

The perfection of Nina Pens Rode’s performance, seldom remarked on, is very much a matter of its capacity to absorb these contradictions. Consider her cracked, fragile voice (which enters another realm entirely when she sings, a difference enhanced by the postdubbing of the music), her confident ironic smile, her girlish gestures around Erland (such as her pendulum-like swings toward and away from him when they sit together at their last meeting), her measured, parsimonious movements around a room. These disparate traits and others have a kaleidoscope effect quite distinct from Falconetti’s more concentrated Jeanne d’Arc— an equally nonnarrative, nondeveloping character also conceived as a form of unwavering intensity.

GERTRUD as Adaptation

Disregarding the play for the moment, the film unfolds roughly as follows:

1. On the eve of his appointment as a cabinet minister, and immediately after a visit from his elderly mother, Gustav Kanning, a liberal, middle-aged lawyer living in Copenhagen, is told by his wife Gertrud that she no longer wants to continue their marriage. Under his questioning, she admits that she loves another man (whose identity she refuses to reveal) but has not yet slept with him. Before she leaves, ostensibly for the opera to see Fidelio, Gustav and Gertrud plan to attend a banquet honoring the fifty-year-old poet Gabriel Lidman, a former lover of Gertrud before she met Gustav, who is returning from abroad for the ceremony.

2. In a park, Gertrud meets the young composer and pianist Erland Jansson, a pampered enfant terrible who is the object of her love. After she tells him of her decision to leave her husband, and recalls in a flashback her previous visit to Erland’s flat, when she sang one of his compositions, they leave together for his flat to make love. At her request, Erland plays one of his pieces while she undresses in the next room.

3. Alone in a carriage, on his way back from a board meeting, Gustav experiences a sudden desire to see Gertrud again (expressed in off-screen narration in past tense) and decides to meet her at the opera. He learns from an attendant that she has not been there all evening.

4. At the banquet for Gabriel Lidman, Gertrud develops a headache during her husband’s speech and goes into the adjacent sitting room, where she is joined by her old friend Axel Nygren, visiting from Paris, who discusses with her free will and his psychiatric research there. Looking up at a tapestry on the wall, Gertrud is shocked to find a dream that she had previously described to Erland — being chased naked by a pack of dogs — virtually reproduced. When Axel leaves, she is joined by Gustav, agitated by her absence from the opera, her recent refusals to sleep with him, and her decision to leave him. Then, when he is called away by the Vice-Chancellor, she is joined by Gabriel, still in love with her, who reveals having attended a courtesan’s party the night before — a party that Gertrud had begged Erland not to attend — where he heard Erland drunkenly boasting of his conquest of Gertrud. After Gabriel bursts into tears and leaves, Gustav returns with the Vice-Chancellor and asks Gertrud to sing for him, enlisting Erland as accompanist. While singing, Gertrud faints.

5. In the park, Gertrud meets Erland and urges him to run away with her, offering to support him. He refuses, confessing that he is committed to another older woman who helped him when he was penniless and is now pregnant by him. He suggests that Gertrud remain with Gustav and continue their affair, and invites her to return with him to his flat, but she refuses.

6. Back in the Kanning flat, Gabriel comes to call. While Gustav is out of the room, Gabriel begs Gertrud to live with him again, but she refuses, and recalls in a flashback how she left him in Rome years before after finding a note on his desk which said, “A woman’s love and a man’s work are in conflict from the beginning.” After Gustav returns, Gertrud goes to phone Axel, saying that she’s coming to Paris to attend lectures at the Sorbonne and wants to join his psychiatric research group. Before Gabriel leaves, Gustav announces that he has just accepted the post of cabinet minister. Then he pleads with Gertrud once again to remain with him, even if she continues her affair; but Gertrud insists that she’s leaving alone, and does so.

7. Thirty or forty years later, Axel comes to visit Gertrud at her house in the country, where she lives alone. She tells Axel she has no regrets for the life she has led and returns all his letters of friendship to her, which he burns in the hearth. She reads him a poem she wrote when she was sixteen, which she describes as her “gospel of love,” and mentions that she has already selected her grave site and the inscription, “Amor Omnia” (Love Is Everything). Axel leaves her after they have said goodbye for the last time.

Because Söderberg’s play has never been available in English, non-Scandinavian Dreyer criticism generally has next to nothing to say about it. Fortunately, a French translation exists — published in La Grande Revue in 1908 — and it reveals that the film is anything but a close adaptation, even though most of the dialogue can be traced back to Söderberg. An elaborate series of cuts, additions, alterations, and transpositions preserves the main plot while markedly changing both the characters and parts of the story’s meaning.

To cite only a few of the most conspicuous differences: in the original, Gertrud has had a child by Gustav who has died in infancy; Gabriel (a playwright, not a poet) has a Spanish wife; there are many references to the politics of the day, and the setting is Stockholm, not Copenhagen; Gustav’s mother visits him not only in the first act but at the end of the third, after Gertrud’s departure, and a subplot charts both her cultivation of young male singers and her failure to visit a poet, a former lover, on his deathbed. Gertrud recounts the same dream with the dogs, but there is no tapestry to reproduce it. At the banquet, many additional characters figure, including a mysterious female “shadow” who appears before Gertrud in Strindbergian fashion to recite a short poem which, in the film, becomes her own “gospel of love” at sixteen. The “Amor Omnia” inscription is one that Gabriel recalls seeing with Gertrud one spring night on the grave of a stranger.

Both flashbacks, Gustav’s carriage ride and the love scene in Erland’s flat are alluded to but not shown; when Gertrud breaks with Gabriel in Rome, he is suffering from writer’s block — which motivates the note on his desk — and it is long after they have ceased living together. All the characters in the play are somewhat coarser, their motivations less pure — especially Gabriel, who is more of a wastrel, and Gertrud, whose cruel streak and chatter make her distinctly less heroic. (“Do you want the brutal truth?” she asks Gabriel in the third act. “I could love you once more if you could make yourself thirty again.”) Most important of all, Axel and everything he represents — friendship, psychoanalysis, a belief in free will — are nowhere to be seen; and when Gertrud leaves Gustav in the third act, it is not clear where she is going.

According to Dreyer, most of the epilogue is derived from a letter from Maria yon Platen to John Landqvist. Without this letter as evidence, it is all too tempting to read both the epilogue and Axel and Gertrud’s early involvement with psychoanalysis as a personal catalyst on Dreyer’s part which transforms the meaning of everything else. Yet if we assume that his use of yon Platen’s life is as creatively selective as his reworking of Söderberg, it is hardly excessive to claim that he was interested in achieving something more than mere documentation. In broad terms, his major contribution to the play is a purification of Gertrud’s character which places her well beyond the bitter misogyny of the original, privileges and extends both her constancy and her martyrdom over several decades, and infuses her with an ambiguity regarding the origin, endpoint, object, and nature of her obsession with love.

GERTRUD as Passage and Process

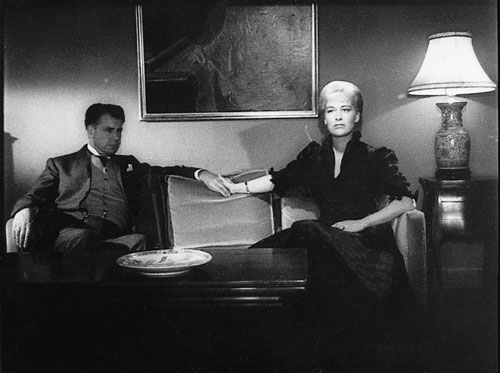

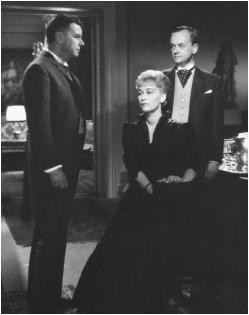

If Dreyer’s film . . . doesn’t function formally as a dream, it nevertheless . . . prescribes an “oneiric” vocabulary: at once the telling of a dream and a session of analysis, an analysis in which the roles are ceaselessly changing; subjected to the flow, the regular tide of the long takes, the mesmeric passes of the incessant camera movements, the even monotone of the voices, the steadiness of the eyes — always turned aside, often parallel, towards us: a little above us — the strained immobility of the bodies, huddled in armchairs, on sofas behind which the other silently stands, fixed in ritual attitudes which make them no more than corridors for speech to pass through, gliding through a semi-obscurity arbitrarily punctuated with luminous zones into which the somnambulists emerge of their own accord . . . — Jacques Rivette, 1969

The darkness has formed a pearl,

The night has borne a dream.

Hidden, it will grow inside me,

Blindingly white and tender.

— Second verse of Erland Jansson’s “Serenade,” sung by Gertrud

A ghost sonata, GERTRUD summons up other obsessive and haunted memory films — THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, LOLA MONTÈS, LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD, THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, INDIA SONG — as well as phantoms of the films Dreyer wanted to make but couldn’t during the last years of his life: MARIE STUART, MEDEA, LIGHT IN AUGUST, AS I LAY DYING, JESUS — all steps toward what he conceptualized as film tragedy.

Theorists are fond of noting that film and psychoanalysis started at about the same time, and the hypnotic nature of the medium runs parallel to the notion of projections on a dream screen. Dreyer’s return to his origins, like Gertrud’s eventual return to the town of her birth, thus suggests the origins of cinema as well as desire, and critics who have regarded GERTRUD as “out of date” are not entirely wrong: it is certainly out of its time. Intimately bound up with questions about identity and the self, it transforms a once contemporary play into a perpetually unfashionable, seemingly atemporal memory film that is as much concerned with echoes and overtones, auras and afterimages as with the remote and often inaccessible events that produce them.

The trance-like rhythm caught by Rivette, evocative of the psychoanalytic session, combines two simultaneous cognitive modes — “the telling of a dream and a session of analysis” — which invite identification and detachment alike. While presenting Gertrud to us in very much the way that she views (and remembers) herself, the film also allows us to see beyond her self-image, however narrow the world may be which circumscribes it. This distance is more apparent in the prints of GERTRUD that mainly circulate today, missing the four rhymed intertitles which separated the three acts and epilogue in the original 1964 release version, all addressed by Gertrud to herself (and written for Dreyer by Grethe Risbjerg Thomsen, who also contributed the song lyrics). Whether Dreyer himself removed these titles is unclear, but he did voice some misgivings about them to Borge Trolle in Kosmorama (“They didn’t quite fulfill the purpose I had for them”), while adding the intriguing suggestion that had the film been in color, they wouldn’t have been necessary.

Because these verses are difficult to come by today, it seems worth reproducing them in full (translated literally from the French version of the script, where they also appear without rhyme or meter):

1

You dreamt of a beloved hand

That could break your chains.

A sudden murmur shatters

The silence of your joyless house.

You leave now, your heart

Overflowing with tenderness

Toward your beautiful dream of happiness.

2

A new lucidity in your heart

Has filled your life with warmth.

Troubled, you keep watch over your love

But your happiness is without peace.

Among all those people who ignore it.

3

Your dream is finished. Only the truth remains.

Hard as stone, To that you were always faithful.

Deep is your suffering, pure is your heart

While the night encircles you.

4

Spring and winter pass

Back in the town of your birth.

Here you are, alone and old

And far from your memories.

This one must know: To be able to grow old gracefully

Only two things exist: Love and death, nothing more.

Dreyer’s films tend to pose themselves as challenges to belief rather than as beliefs that demand simple adoption, and this is a stumbling block for many spectators. The sainthood of Jeanne d’Arc, the supernatural postulates of VAMPYR, the acceptance of witchcraft at the end of DAY OF WRATH, and the miracle at the end of ORDET are all imposed on the plots as formal necessities; yet our inability to accept any of these facts wholeheartedly is central to the impact of these films. A comparable problem relates to the idealism and self-image of Gertrud, and considering the laughter that initially greeted the above verses, it seems possible that Dreyer decided they overwhelmed the more objective side of the film.

Whatever the reason for their absence today, there are many other instances of Gertrud’s love as self-love — including the verse from Jansson’s “Serenade” quoted above. Significantly, the water in the pond behind her and Erland forms a placid mirror to a stately line of trees at their first park meeting, a reflection broken by a drifting, riddled turbulence at the second. Like the mirror given to Gertrud by Gabriel (visible in the Kanning parlor) and the one given to her by Gustav (which remains off-screen), these surfaces all suggest portals of narcissism, judged and placed according to the self-image they throw back; and the ones tied to her love for Erland are solipsistic as well — nature reduced (or expanded) to the dimensions of her self-infatuation. “Strange woman,” says Erland in his flat, shortly before they kiss. “Who are you?” “I’m many things. Dew which falls from the leaves. White clouds that pass aimlessly. I’m the moon. I’m the sky.” Like the verses, these mirrors function as inner voices more than ornaments — images of the self as a self-enclosed universe.

By contrast, the fires that flicker through GERTRUD usually suggest potential fusions reaching beyond the self: the candles in Gustav’s flat and the ones flanking Gabriel’s mirror in the Kanning parlor; the torches and candles at the banquet; the burning hearth that shimmers behind Gabriel and Gertrud in the third act and glows between Axel and Gertrud in the epilogue (while consuming his letters to her); not to mention the incandescent sunlight that floods both flashbacks and the epilogue. Yet by the end of the film, they have become mirrors too: “I feel as though I’m staring into a fire about to be extinguished,” Gertrud says to Axel just before he leaves. The play’s epigram, transposed by Dreyer to a statement of Gabriel’s recalled by Gertrud, is “I believe in the pleasures of the flesh and the irremediable loneliness of the soul.”

This dialectic between incandescent joining and dark isolation — like the long bouts of inactivity separating the last four features in Dreyer’s career — is harmonized like a treble and bass clef to compose the melody of Gertrud’s longing, metrically spaced in a no less dialectical fashion between development and stasis.

Gertrud as Nonnarrative

Sometimes a conflict emerges between the desire for the image and the desire for the story which is, after all, in psychoanalytic terms, normal, since the first one expresses, beyond the codes of modernism, a specular fascination for the body (of the Mother), and the second, the return of the repressed narrative, and consequently the necessity to pay one’s debt to the Father. — Bérénice Reynaud (1)

Look at me. Am I beautiful? No. But I have loved. Look at me. Am I young? No. But I have loved. Look at me. Do I live? No. But I have loved. — Gertrud’s “gospel of love,” written at the age of sixteen

When Godard defended GERTRUD in the 1960s as “equal, in madness and beauty, to the last works of Beethoven,” one wonders whether he might have been partly thinking of the question and answer written by Beethoven as an epigraph to the finale of the last quartet (the corresponding musical passage figures centrally in 2 OU 3 CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D’ELLE): “Muss es sein? Es muss sein!” (Must it be? It must be!). Poised evenly and unbearably between apologia and critique, GERTRUD can be said to perform the radical step of superimposing that query and response rather than placing them in sequence.

When we first see Axel, we learn from Gertrud that he has written a book on free will; in the epilogue, he presents her with a copy of a new book, on Racine. Gertrud, an atheist, believes in free will, unlike her father, “a sad fatalist” (“He thought that everything was predestined”), and believes, like Axel, that “to wish is to choose.” Yet only a moment later, after Axel mentions studying “psychosis, neurosis, dreams, and symbols” in Paris, she discovers the wall tapestry behind her, a depiction of her recurring dream. Soon afterward, in separate scenes, Gabriel tells her that he “had to” inform her of Erland’s indiscretion, and Erland tells her that he “had to” attend the courtesan’s party. “Had to,” muses Gertrud. “That’s the key word to everything.” Positing the unconscious as tragic destiny, GERTRUD places narrative causality and free will in the same ambiguous category.

The earliest expression of Gertrud’s identity, the poem cited above, comes in the epilogue, just before she tells Axel of the grave inscription she has chosen for herself, “Amor Omnia.” The immediate juxtaposition of these framing badges (or shields) suggests that she has chosen her life, and lived it freely; yet what does this continuum say about her alleged past love for Gabriel and Erland? Having denied beauty, youth, and life itself for an earlier love, she seems to have condemned herself to a compulsive replaying of a fixed past, which implies that her preoccupation with love may be little more than a form of arrested adolescence. Might we not conjecture that Dreyer’s preoccupation with his mother, fixed during his own adolescence, led him to a comparable nonnarrative impasse?

Throughout the film, this tension between freedom and obsession has been materially reproduced in a number of ways. Abrupt cuts to shots when the camera is already in motion (such as the rapid, rapturous track and pan accompanying Gertrud to her first rendezvous with Erland) convey at once the free flux of life and its sense of being achingly just out of reach; the suspension of direct sound for both the musical performances (Gertrud singing with Erland) and the off-screen, past-tense narration (Gustav in the carriage, Gertrud recounting both flashbacks) creates an otherworldly ambience that makes these passages seem to occur outside time. And just as the camera movements that follow the characters define a form of narrative suspension between the stretches of dialogue, the stationary setups recording the dialogue allow the words to take flight: continuous motion and continuous stasis are equally in evidence.

Depending upon their temperaments and predilections, critics have described the film as either full of or devoid of camera movements (rather than somewhere in between). Even a critic as sophisticated as David Bordwell, tied to an exclusively narrative model, can read GERTRUD only as an “empty film,” interpreting nonnarrative as absence rather than as a different form of presence. But the obsessive desire for the image is as central to the meaning of GERTRUD as the habitual desire for the story, and the furious, unceasing tug of war between these desires is the very source of the film’s tragic rhythm. Only Axel, who accepts Gertrud as she is, escapes this tension: her husband must inquire why she is leaving him, her former lover asks repeatedly why she left him, and her present lover can only ask himself whether he loves her. It is only with Axel that Gertrud can have a true conversation, and when she returns his letters and he cheerfully burns them, their joint action is to refuse a narrative together, deny any riddle to be solved.

Insofar as this gesture reflects on Dreyer, it is an autobiographical gesture that paradoxically rejects autobiography. Like Gertrud’s selection of her gravestone, or the film’s final shot of a closed door, it represents an effort to forestall any future Drouzys. Transfixed by a static image of his mother, Dreyer enters a nonnarrative realm that can be associated with both prebirth and death — a state that both precedes and follows any need to acknowledge his father, any necessity to tell a story, placing narrative within parentheses. A work of perpetual time travel, GERTRUD no less forcefully projects a suspended gaze and meditation on a frozen destiny, perfect yet appalling.

1. “New York Independent Cinema,” Fuse (Summer 1985).