Mark Rappaport takes us on a fictional tour through an actor’s career, albeit one supported by a great deal of research and careful film-watching, that proposes some enlightening ways of reinventing how we watch movies, teaching and hugely entertaining us at the same time. Mark’s own accurate synopsis of what he’s doing, reproduced below, is taken from the web site of a film festival held in the Canary Islands — one of the many festivals where the film was shown. — J.R. [4/26/15]

Synopsis

Are you defined by other people and their perceptions of who you are? Or can you exist outside of the arbitrary boundaries which are placed on you? The great French actor Marcel Dalio starred in Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game and Grand Illusion. In both films he plays a character who is Jewish, as Dalio was in real life. In most of his French films of the 30s, he was always “The Jew.” When the Nazis invaded France, he fled to America and appeared in Casablanca and To Have and Have Not. In America, he was no longer “the Jew” but “The Frenchman”…

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 2, 1992). — J.R.

NORTH ON EVERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by James Benning.

A good many of the fine points of the film business elude me. But if I understand some of the current rules correctly, it’s poison to use black-and-white cinematography, letterboxing (for framing wide-screen formats on video), or subtitles –unless they appear in music videos or, in the case of subtitles, in Dances With Wolves or The Last of the Mohicans, when they automatically become commercially desirable.

I cite these ridiculous rules of thumb to show just how fanciful most such commercial “rules” turn out to be. Producers, distributors, and exhibitors often claim that their choices are dictated by the well-researched desires of audiences; of course audiences counter that they can only choose from what’s put in front of them. In other words everyone passes the buck when it comes to explaining why black-and-white features can’t get bankrolled in this country and why foreign-language films have a tough time — only 1 percent of all movies shown here are subtitled. And the industry takes enormous pains to ensure that we don’t see letterboxing on TV or video — except on MTV. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1992). — J.R.

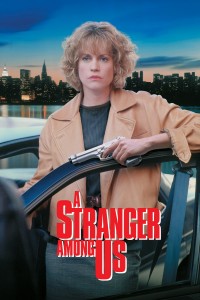

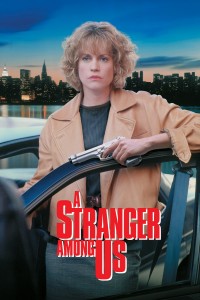

There’s apparently something about Hasidic Jews that makes normally talented and reasonable filmmakers — David Mamet in Homicide, screenwriter Robert J. Avrech (Body Double) and director Sidney Lumet here — turn otherwise straightforward thrillers into harebrained hootfests. The best that can be said for this movie, which stars Melanie Griffith as an underground cop who lives with the Hasidim of Brooklyn while trying to solve the murder of a jewel merchant, is that apart from the talents of Griffith and Eric Thal (who plays a young Hasidic Jew she mildly flirts with) it has some educational value as a form of exposition about a fascinating subculture. The worst is that most of the other actors (and characters for that matter) get bent out of shape while trying to conform to the contours of the dotty plot. With John Pankow, Tracy Pollan, Lee Richardson, Mia Sara, Jamey Sheridan, Burtt Harris, and a lot of quotes from the cabala. (JR)

Read more

From the September 15, 1995 issue of Chicago Reader. —J.R.

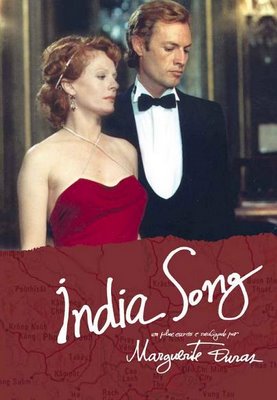

Films by Marguerite Duras

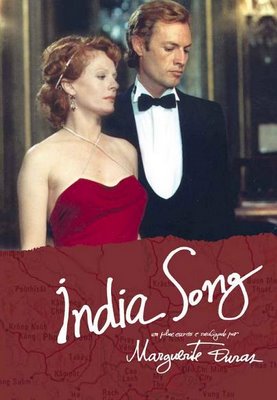

It’s surely indicative of the scarcity of Marguerite Duras movies that even a dedicated fan like me has managed to see only seven of them — and for one of those I had to drive 100 miles, from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles. No Duras film has been distributed in the United States for years, and in preparing this article I wasn’t even able to obtain a complete filmography; my own provisional list includes 20 titles, stretching from La musica in 1966 to Les enfants in 1982.

If one extends this list by adding adaptations (by herself and others) of Duras literary works, the scripts she wrote for other directors, and two films by Benoit Jacquot revolving around Duras, the figure is 31 films, most of them features. So it’s no small achievement that Facets Multimedia (which, thanks to the efforts of Charles Coleman, has recently featured such adventurous fare as Manoel de Oliveira’s Valley of Abraham and an exhaustive Nanni Moretti retrospective) will be showing a dozen films from this list over the next couple of weeks, most of them in brand-new prints and most of them four to six times. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 8, 1995). — J.R.

I Am Cuba

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Mikhail Kalatozov

Written by Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Enrique Pineda Barnet

With Luz Maria Collazo, Jose Gallardo, Sergio Corrieri, Maria Gonzalez Broche, Raul Garcia, and Jean Bouise.

Undeniably monstrous and breathtakingly beautiful, ridiculous and awe inspiring, I Am Cuba confounds so many usual yardsticks of judgment that any kind of star rating becomes inadequate. A delirious, lyrical, epic piece of communist propaganda from 1964 — at least three years in the making and 141 minutes long–it is simply too campy and too grotesque to qualify as a “masterpiece,” but I’d probably care less about it if it were one. A “must-see” may come closer to the mark, but it certainly isn’t a must-see for everybody. This movie has been rattling around in my head since I first encountered it 16 months ago, yet I can’t say it won’t enrage some people and bore others. Worth seeing? Has redeeming facet? Worthless? It fits all and none of these categories. To put it simply, the world doesn’t make allowances for a freak of this kind.

A Russian-Cuban production, it reportedly was hated in Russia and Cuba alike in the mid-60s, at least among government officials; in Cuba it was commonly known as I Am Not Cuba. Read more

From the January 29, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This 1992 French feature by Leos Carax (Boy Meets Girl, Bad Blood) could be the great urban expressionist fantasy of the 90s: like Sunrise and Lonesome in the 20s and Playtime and Alphaville in the 60s, it uses a city’s physical characteristics to poetically reflect the consciousness of its characters. Carax daringly and disconcertingly begins the film as a documentary portrait of the homeless in Paris, but it becomes a delirious love story between two people (Denis Lavant and Juliette Binoche) who live on one of Paris’s most famous bridges and experience the whole city as a kind of enchanted playground, a vision that reaches an explosive apotheosis during a bicentennial fireworks display over the Seine. To realize his lyrical and monumental vision, Carax built a huge set in the French countryside that depicted Pont-Neuf and its surroundings, making this one of the most expensive French productions ever mounted. So the film seems an ideal subject for a lecture by former Chicagoan Stuart Klawans, film critic for the Nation and author of Film Follies: The Cinema Out of Order, a new book with a witty and highly original sense of film history. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 10, 1992); also reprinted in two of my collections, Placing Movies and Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

OTHELLO

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Orson Welles

With Orson Welles, Micheal Mac Liammoir, Suzanne Cloutier, Robert Coote, Fay Compton, Doris Dowling, and Michael Laurence.

Sustained until death at 70 by his fame as the prodigy with the baby face, Orson Welles always appeared to abide by words he put in the mouth of Citizen Kane: “There’s only one person in the world to decide what I’m gonna do — and that’s me.” — from a two-page magazine ad for the Dodge Shadow that appeared last month under the heading “Amazing Americans . . . a celebration of people who have lifted our nation’s pride”

I guess this describes the official Orson Welles we’re all supposed to love and revere. The ad demonstrates how even the recalcitrance of a wasted and abused artist can wind up as a handy marketing tool. Chrysler, a corporation that never would have dreamed of sustaining, much less supporting Welles as an artist when he was alive — and surely wouldn’t pay a tenth of what this ad cost to help make his unseen legacy available today — proudly invites us to join it in celebrating his artistry. Read more

From the April 1. 1992rChicago Reader. — J.R.

The success of John Cassavetes’s independent Shadows led to a contract with Paramount that yielded only this feature, Cassavetes’s second — a gauche but sincere drama with a highly relevant subject: the self-laceration and other forms of emotional havoc brought about when a footloose jazz musician (Bobby Darin) decides to sell out and go commercial. A lot could be (and was) said about what’s wrong with this picture: it’s pretentious, lugubrious, mawkish, and full of both naivete and macho bluster. It also has moments that are indelible and heartbreaking, at least one unforgettable performance (Everett Chambers as the hero’s manager), and many very touching ones (by Darin, Stella Stevens, Rupert Crosse, Vince Edwards, Cliff Carnell, and Seymour Cassel, among others), not to mention a highly affecting jazz score featuring Benny Carter and a haunting theme by David Raksin. If you care a lot about Cassavetes, you should definitely see this — otherwise keep your distance (1960). (JR)

Read more

Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader in their Christmas issue (December 25) in 1992. — J.R.

The presumption behind most ten-best lists is that they include items available to everybody. One can always look at such lists and say, “Too bad I missed such and such. Maybe I’ll catch up with it on video.” But few people seem to be aware that they may never catch up with a film, because it never made it to Chicago at all—either to theaters or to video stores. In a consumer culture like ours we aren’t supposed to think too much about what merchandisers choose to put in front of us; it’s better for business if we assume that new movies just fall from the sky into theaters and video stores—and that those that don’t make it don’t deserve to. However, I see a certain number of movies in other countries every year that don’t make it to town, and sometimes they’re better than the movies that do. Why this happens so often is a matter worth exploring briefly.

In 1938 the U.S. government filed an antitrust action against Paramount Pictures, objecting to the monopolies of movie theaters held by the studios. By the end of 1946 a court judgment enjoined not only Paramount but also Loew’s, RKO, Warner Brothers, and 20th Century-Fox from acquiring additional theaters. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1992). — J.R.

Now we all know what German expressionism is: extended chunks of Bergman’s Sawdust and Tinsel (recast with John Malkovich and Mia Farrow) and The Magician (recast with Kenneth Mars and Woody Allen), Nosferatu’s pointed ears, the dull center framing of any Woody Allen movie (no diagonals or tilted angles, please), lots of kvetching with New York accents, central-casting prostitutes played by guest stars (Lily Tomlin, Jodie Foster, and Kathy Bates), reams of dialogue we’ve all heard before in countless other movies, a strangler lurking in dank cobblestone alleyways, the opening passage of Kafka’s The Trial (who needs to read any further?), music by Kurt Weill, and, to top it off, shadows, silhouettes, and fog filmed in black and white. In short, Woody Allen’s feeblest semicomedy and postmodernist pastiche since A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, bravely forsaking the streets of Manhattan for the soundstages of Astoria, explores the dark night of the soul with lots of famous people. With Michael Kirby, Donald Pleasence, Philip Bosco, Kate Nelligan, Julie Kavner, John Cusack, Madonna (for a minute or two), and others I’ve undoubtedly forgotten. You’ll forget them, too. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Sight and Sound (October 1992). –- J.R.

Most of the American press has been all too happy to declare the new version of Orson Welles’ Othello as “expertly restored”, as Vincent Canby put it in the New York Times. But restored from what and to what? Even rudimentary information about the film’s original form is not easy to come by in the U.S., where 0thello brought in only $40,000 on its belated first release in 1955 and has been screened only sporadically since. Mutatis mutandis, the acclaim that has greeted the restoration recalls the unqualified press endorsements of Francis Coppola’s presentation of Abel Gance’s ‘complete’ Napoléon at Radio City Music Hall in 1981, in a version that eliminated an entire subplot so that the print wouldn’t run past midnight and jack up the theatre’s operating costs.

To make matters more complicated, two different versions of the ‘restored’ Othello have been presented to the public so far, although only the second of these is currently in circulation. The first, worked on in Chicago by a team headed by Michael Dawson and Arnie Saks, premiered at New York’s Lincoln Center late last year; I saw it several weeks afterwards at a private screening in Chicago. Read more

From the November 1, 1992 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last feature (1975) is a shockingly literal and historically questionable transposition of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom to the last days of Italian fascism. Most of the film consists of long shots of torture, though some viewers have been more upset by the bibliography that appears in the credits. Roland Barthes noted that in spite of all its objectionable elements (he pointed out that any film that renders Sade real and fascism unreal is doubly wrong), this film should be defended because it refuses to allow us to redeem ourselves. It’s certainly the film in which Pasolini’s protest against the modern world finds its most extreme and anguished expression. Very hard to take, but in its own way an essential work. In Italian with subtitles. 117 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 6, 1994). I haven’t reseen The Second Heimat since then, and it would be interesting to discover how it holds up today. — J.R.

**** THE SECOND HEIMAT

(Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Edgar Reitz

With Henry Arnold, Salome Kammer, Daniel Smith, Noemi Steuer, Armin Fuchs, Martin Maria Blau, Laszlo I. Kish, Frank Roth, Anke Sevenich, Franziska Traub, Michael Schonborn, Hannelore Hoger, Susanne Lothar, Alexander May, and Peter Weiss.

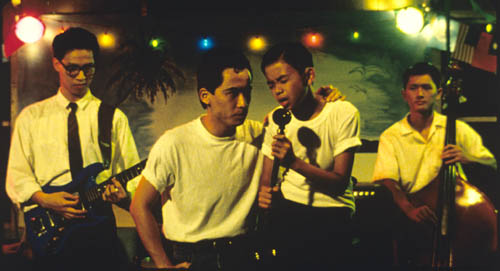

Why is it so hard to be happy? — Clarissa in the seventh episode of The Second Heimat

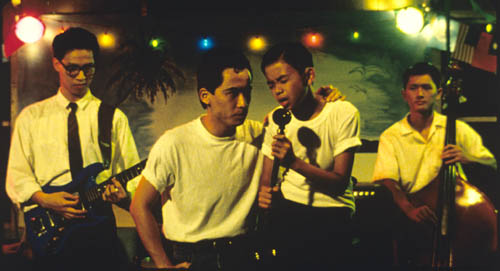

The 60s and early 70s reveled in long, ambitious works — movies and music alike — epic, multilayered statements that through their unwieldy lengths alone challenged and disrupted the flow of everyday life. In jazz there were Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz and John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, in rock Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, We’re Only in It for the Money, and Tommy, and when rock and movies came together in Woodstock (1970) the running time was three hours — about as long as a marijuana high.

An interesting paradox: to go to a long concert or long movie during that period was to be “somewhere else,” but that didn’t necessarily mean to escape. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 22, 1991). — J.R.

GUILTY BY SUSPICION

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Irwin Winkler

With Robert De Niro, Annette Bening, George Wendt, Patricia Wettig, Sam Wanamaker, Barry Primus, Gailard Sartain, Chris Cooper, Ben Piazza, and Martin Scorsese.

There are plenty of bones one can pick with Guilty by Suspicion, the first Hollywood feature devoted in its entirety to the film-industry blacklist (The Front dealt with TV). Of course there are plenty of bones one can pick with just about any movie, if one is so inclined. But critics, at least, seem more inclined to be so inclined with movies that deal with political subjects. This is not to say that most critics reprove such movies on political grounds; on the contrary, they usually harp on other aspects. But one still winds up feeling that it’s frequently the politics that gets their hackles up.

Having seen this movie more than a week later than most of my colleagues, due to some interesting circumstances that I’ll discuss later, I’ve had ample opportunity to read and (more often) hear some of their carping, most of it hyperbolic invective about the acting and directing. Some of them have expressed so much antipathy for the picture that I went to the first screening at Webster Place last weekend expecting the worst. Read more

From the August 17, 2001 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Apocalypse Now Redux

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Written by John Milius and Coppola

With Martin Sheen, Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, Laurence Fishburne, Dennis Hopper, G.D. Spradlin, Harrison Ford, Colleen Camp, Cynthia Wood, Christian Marquand, and Aurore Clement.

It’s hard to think of many movies where the great, the not so great, and the simply awful coexist quite as brazenly as they do in Apocalypse Now. This was true in 1979, when the movie clocked in at 150 minutes, and it’s true 22 years later, when the new version, Apocalypse Now Redux, runs a third longer.

If anything, the longer version — not so much a rethinking of the material as an expansion, with a minimum of reshuffling, by the adept Walter Murch, who also worked on the original — is better and worse, emphasizing both the ambitious scope and the fatal flaws of Francis Ford Coppola’s achievement. Among the more substantial additions are a ghostly sequence set on a French plantation (featuring Aurore Clement and the late Christian Marquand) that tries, with mixed results, to poeticize the futility of outsiders, French or American, getting involved in the Vietnam war and a silly and rather inconclusive sequence involving a couple of Playboy Playmates (Cynthia Wood and Colleen Camp) that adds nothing. Read more