From the Chicago Reader (December 14, 2001). — J.R.

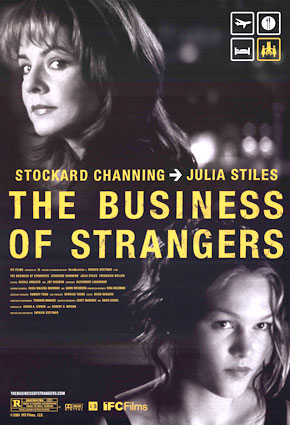

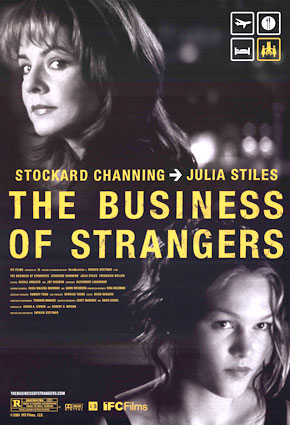

The Business of Strangers

**

Directed and written by Patrick Stettner

With Stockard Channing, Julia Stiles, Frederick Weller, Jack Hallett, and Marcus Giamatti.

The most notable thing about The Business of Strangers, as Andrew Sarris recently suggested in the New York Observer, may be the conjunction of three facts: that the central character of this first feature is a middle-aged woman executive, that it was written and directed by a man, and that it isn’t misogynist.

This sounds like some PC brief, which isn’t generally a good reason for recommending a film. Yet The Business of Strangers doesn’t have any ideological axes to grind, though it’s interested in ideological exploration. And that points to a kind of respect for its audience, not merely a respect for its leading character.

Several reviewers have noted this picture’s resemblance to In the Company of Men, Tape, and Safe. Though I wouldn’t deny the parallels, they generally have more to do with surface effects than overall meaning. Like In the Company of Men, The Business of Strangers focuses on characters in the business world who display predatory behavior in anonymous surroundings — Anywhere, USA — and it uses a percussive score to suggest these characters’ hostilities and power games. Read more

A kind of ten-best meditation for Artforum, December 1995 (vol. 34, issue 4), that anticipates some of my arguments in my subsequent book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See. Incidentally, I’ve since then come to value Showgirls (and, more generally, Paul Verhoeven) far more than I did 25 years ago, politically and otherwise. — J.R.

In October I compiled three lists for my own schizoid edification. The first consisted of the 50 best films I had seen this year at festivals in Berlin, Cannes, Locarno, and Toronto and as a member of the New York Film Festival selection committee (which entailed a screening of 100 more films in August). The second was my impression of what comprised the 50 most discussed films released in the United States this year; my third list was a selection of what I considered the 20 most important releases, whether they were widely discussed or not. Only one feature appears on all three lists — Todd Haynes’ Safe.

One reason for the lack of overlap between my three lists is that, unless it’s a big-studio product, a film usually takes at least a year to open commercially in the United States after its premiere at festivals, ensuring that we remain something of a last-stop backwater when it comes to most non-Hollywood movies. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 27, 1989). — J.R.

NANOU

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Conny Templeman

With Imogen Stubbs, Jean-Philippe Ecoffey, Christophe Lidon, Valentine Pelka, Roger Ibanez, Daniel Day Lewis, and Lou Castel.

WE THE LIVING

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Goffredo Alessandrini

Written by Anton Giulio Majano

With Alida Valli, Rossano Brazzi, Fosco Giachetti, Emilio Cigoli, Cesarina Gheraldi, Giovanni Grasso, and Guglielmo Sinaz.

There’s obviously a world of difference between Nanou, a low-budget Anglo-French coproduction of 1986, playing this week at the Film Center, and We the Living, a big-budget Italian movie of 1942, adapted from Ayn Rand’s first novel, playing this week at Facets Multimedia. But in certain areas they have an interesting relationship to one another. Both films come to us filtered through diverse national contexts, and both are love stories in which intense political commitment plays a substantial role — a role that is erotic as well as ideological and ethical in its implications. Where they differ most strikingly is in their underlying political assumptions, and in the way their narratives relate to those assumptions.

Nanou, shot entirely on locations in France and Switzerland and utilizing mainly French dialogue, is nonetheless an English film, in style as well as overall conception. Read more

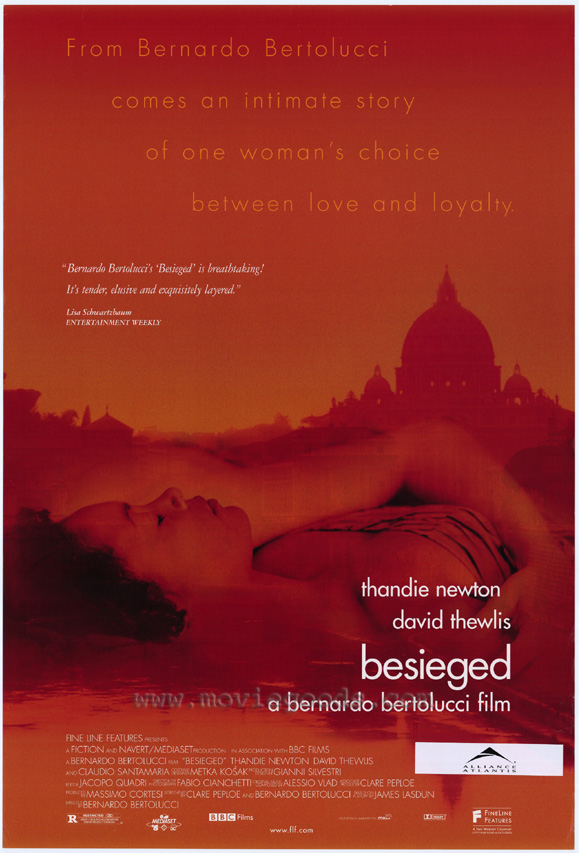

From the June 11, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Besieged

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Bertolucci and Clare Peploe

With Thandie Newton, David Thewlis, and Claudio Santamaria.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Many times over the past three decades I’ve been close to giving up on Bernardo Bertolucci. The rapturous lift of his second feature, Before the Revolution (1964), promised more than he seemed prepared to deliver with the eclectic Partner (1968). Yet it was The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) rather than The Conformist (made just afterward and released the same year) that renewed my faith in his talent. Both movies, like Before the Revolution and Partner, were the flamboyant expressions of a guilt-ridden leftist, a spoiled rich kid with a baroque imagination and a social conscience that yielded dark and decadent ideas about privilege and guiltless fancies about sex. Where they differed for me was in the degree to which The Conformist succumbed to fashionable embroidery, a stylishness that took the place of style.

It was the relatively big budget The Conformist, an adaptation of an Alberto Moravia novel, that made Bertolucci’s name in the world market and so influenced American movies that Coppola’s Godfather trilogy would have been inconceivable without it. Read more

Here are two recent valuable acquisitions I’ve made via French Amazon — Antoine de Baecques’s 940-page biography of Jean-Luc Godard, the first one in French (after two in English, by Colin MacCabe and Richard Brody), published by Bernard Grasset, and Godard’s 107-page “book” version of (or companion to) his recent Film Socialisme, published by P.O.L, his usual publisher, and subtitled Dialogues avec visages auteurs (literally, “Dialogues with faces authors”).

It’s far too early to make any sweeping judgments about either book — which would be presumptuous for me to attempt to do at any point, given my less than perfect French — but a few first impressions are in order. De Baecque’s biography is full of interesting details, in particular ones drawn from formerly unavailable or unfamiliar documents, e.g., a letter from Pasolini to Godard about La chinoise, and, roughly two decades later, a letter from Godard to Norman Mailer about some of his plans for King Lear. But it also appears that De Baecque can’t be trusted very much when it comes to his handling of American criticism about Godard. A minor complaint (which I hope doesn’t sound churlish, given how flattering he is to me elsewhere in this book): he claims, based on the French translation of my autobiographical Moving Places, that I spent “half my time in Paris between 1966 and 1968” seeing or reseeing Godard films on drugs; but in fact, apart from a couple of summer visits to Paris during this period (during which my Godard viewing goes unmentioned), my extended sojourn in Paris was between 1969 and 1974, and my accounts of watching Alphaville on grass and Band of Outsiders on acid on the pages he cites were actually in New York in 1965 and in London in 1970, respectively. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 12, 1988). — J.R.

THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Kaufman and Jean-Claude Carriere

With Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, Lena Olin, Derek de Lint, Erland Josephson, Pavel Landovsky, Donald Moffat, and Daniel Olbrychski.

Before we are forgotten, we will be turned into kitsch. Kitsch is the stopover between being and oblivion. — Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The semibearable heaviness of Philip Kaufman, at least in his last three features — Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Wanderers, and The Right Stuff — is largely a matter of an only half-disguised didactic impulse, a notion that he’s got something to teach us. For a filmmaker as commercial as Kaufman, this impulse becomes worrying chiefly because we emerge from his movies not knowing anything essential that we didn’t know before we went in. We’ve submitted ourselves to a certain intelligence, grandiosity, and slickness, and we may well have been entertained — Kaufman has undeniable craft as a storyteller — but it’s questionable whether we’re any wiser.

There’s nothing at all disgraceful about this. But the suggestion that we’re supposed to be getting something more than intelligent entertainment from a Kaufman film — which seems to hover over every frame like an admonition, almost a threat — leaves an unsatisfying aftertaste. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1973/4). For a subsequent production story about this film written for Film Comment, devoted mainly to a day of studio shooting, go here. –- J.R.

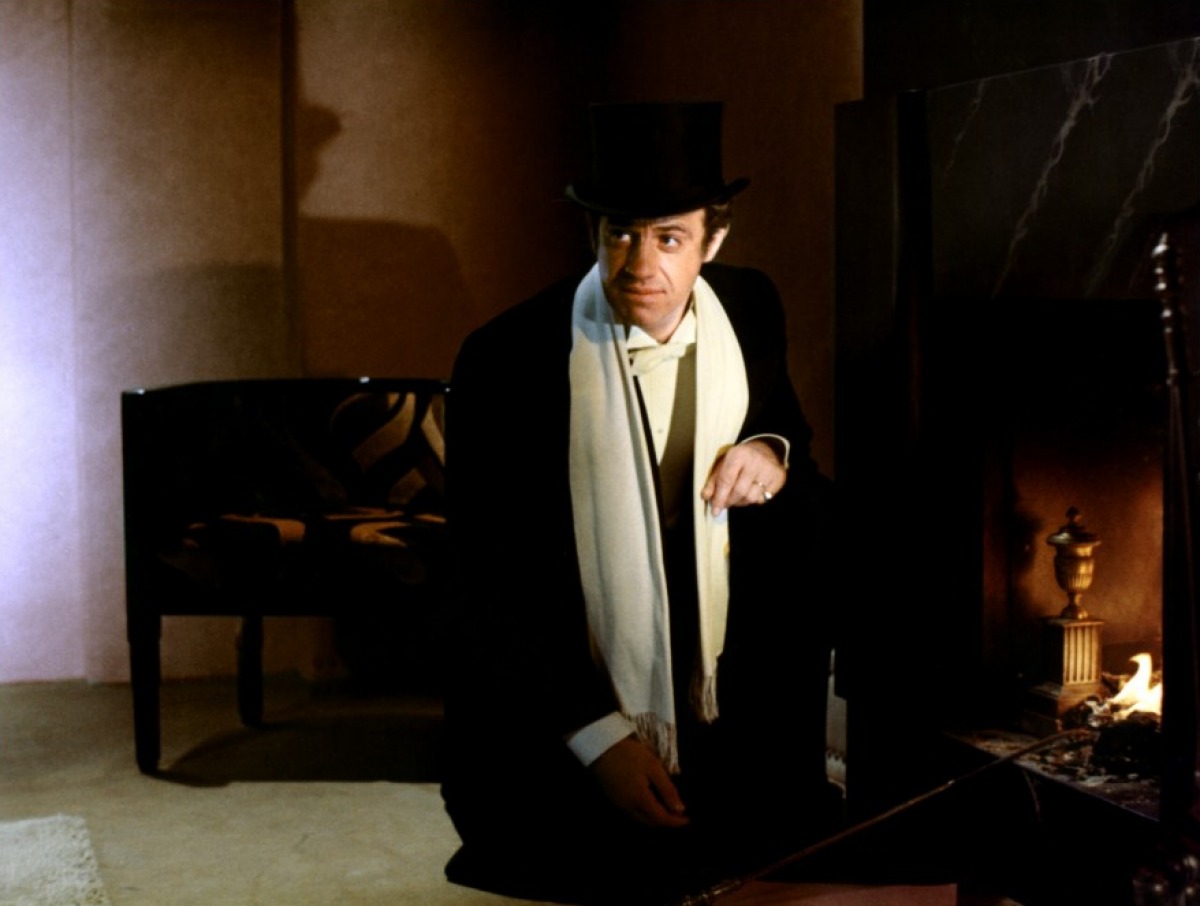

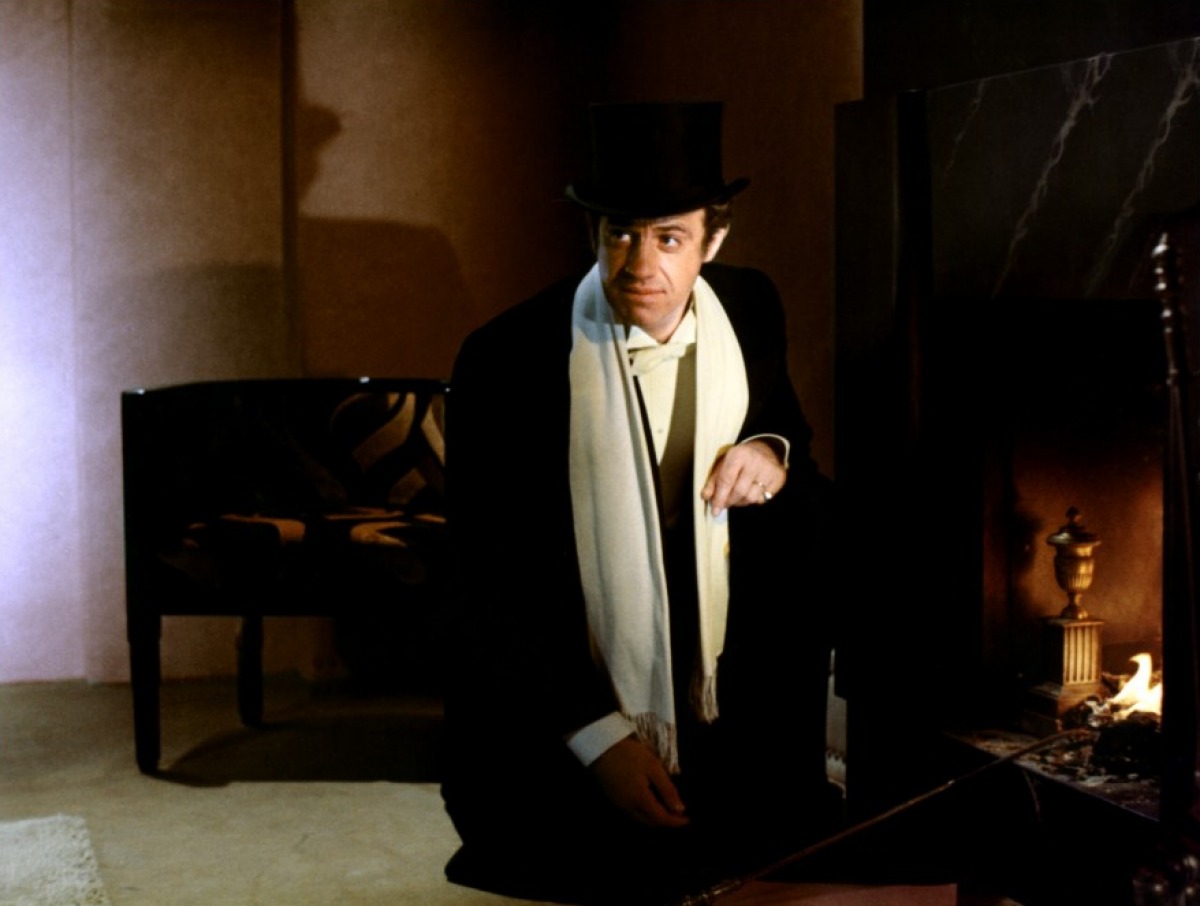

Since the beginning of October, Alain Resnais has been shooting Stavisky, his first feature since Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968). ‘When Jorge Semprurn first spoke to me about making a film on Stavisky,’ Resnais said recently, ‘I admitted to him that at the age of twelve, in the Musée Grévin, I stood dreaming before the wax figure of this character, whom I compared to an Arsène Lupin swindling the rich and helping the poor.’

Actually, Serge Alexandre Stavisky (born in Russia as Sacha) was a swindler who sold 40 million francs’ worth of valueless bonds to French workers, but he moved about in high circles. In spite of a shady past, he was generally known in the early 1930s as a respectable financier with first-rate political connections, associated with the municipal pawnshop of Bayonne. When his fraud was discovered in December 1933, he promptly fled, and the police caught up with him in Chamonix the following month. According to official history, he either committed suicide or was murdered by the police, although the latter explanation appears the likelier one: the Paris press rather implausibly reported that he fired two bullets into his head. Read more

From the Autumn 1977 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

Perhaps it is time to study discourse not only according to its expressive values, or in its formal transformations, but also according to its modes of existence: the modes of circulation, attribution and appropriation of discourse vary with each culture. . . . [T]he effect on social relationships can be more directly seen, it seems to me, in the interplay of authorship and its modifications than in the themes or concepts contained in the works.

— Michel Foucault, “What Is an Author?”

It seems likely that Hollywood Directors 1914–1940 and Movies and Methods[*] are the two most interesting anthologies of writing about film recently published in English. Each marks a substantial foray beyond the standard recycling operations of most anthologies, making available a wealth of helpful material that is otherwise hard to come by. An easy enough assessment, on the face of it, yet one that conceals a nagging question: what do we mean by “interesting” and “helpful”? In what way can both books be considered deserving of the same ambiguous adjectives? How far do they allow themselves to be considered within the same universe of discourse?

First, a few basic distinctions. Read more

One of Raul Ruiz’s best features, this is also one of his looniest — shot in Holland in about a week’s time, although it’s supposedly set in Patagonia. The putative SF plot concerns a French anthropologist and his Dutch wife who are hired to study the indecipherable language spoken by two members of an Indian tribe; in fact, this is a dazzling intellectual goof, with an average of one striking visual idea per shot (the gorgeous color cinematography, including many trick shots, is by the great Henri Alekan, who filmed Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast), a lot of gags involving the pretensions of anthropologists and psychoanalytical theorists, and other forms of nonstop invention. This being a Ruiz film, you shouldn’t expect anything from the story or the performances; the dialogue is in five or six languages (one of them invented), and the lead actress appears to have learned her English lines phonetically (1982, 93 min.).

Read more

Read more

I’ve never been a big fan of Chinese director Chen Kaige’s work, but this opium dream about incestuous longings is clearly his best piece of direction, stylistically voluptuous and pictorial in the best sense. Shot by the remarkable Christopher Doyle, perhaps the most talented cinematographer working in Asia, and starring Gong Li and Leslie Cheung, it’s full of ravishing poetry, even though it isn’t very involving on a narrative level. Since its Cannes premiere it’s been cut by ten minutes or so and decked out with titles intended mainly to clarify the story line and distinguish characters (the usual aim of Miramax’s compulsive meddling), but this has done damage to the film’s hypnotic and hallucinatory rhythms, especially in the early sections. Once one gets past this choppiness, Chen’s use of offscreen sounds as emotional and atmospheric punctuation and his exquisite uses of color, lighting, framing, and camera movement conspire to make this a beautifully overripe example of Baudelairean cinema. Shu Kei wrote the elliptical script, based on a story by the director and Wang Anyi, set in and around Shanghai from 1911 to sometime in the 1920s. Water Tower. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 11, 1997). — J.R.

Men in Black

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Barry Sonnenfeld

Written by Ed Solomon

With Tommy Lee Jones, Will Smith, Linda Fiorentino, Vincent D’Onofrio, Rip Torn, Tony Shalhoub, and Mike Nussbaum.

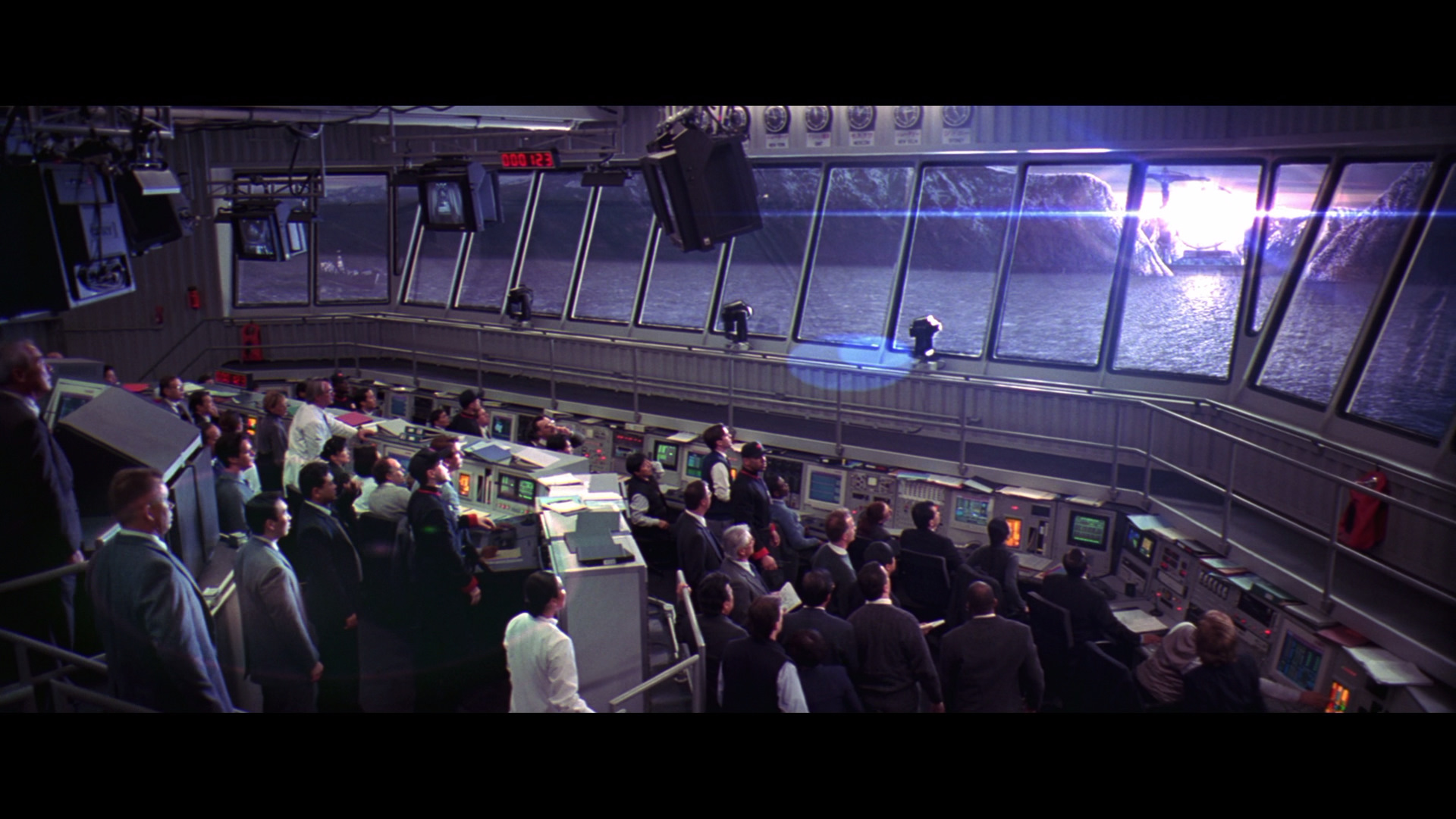

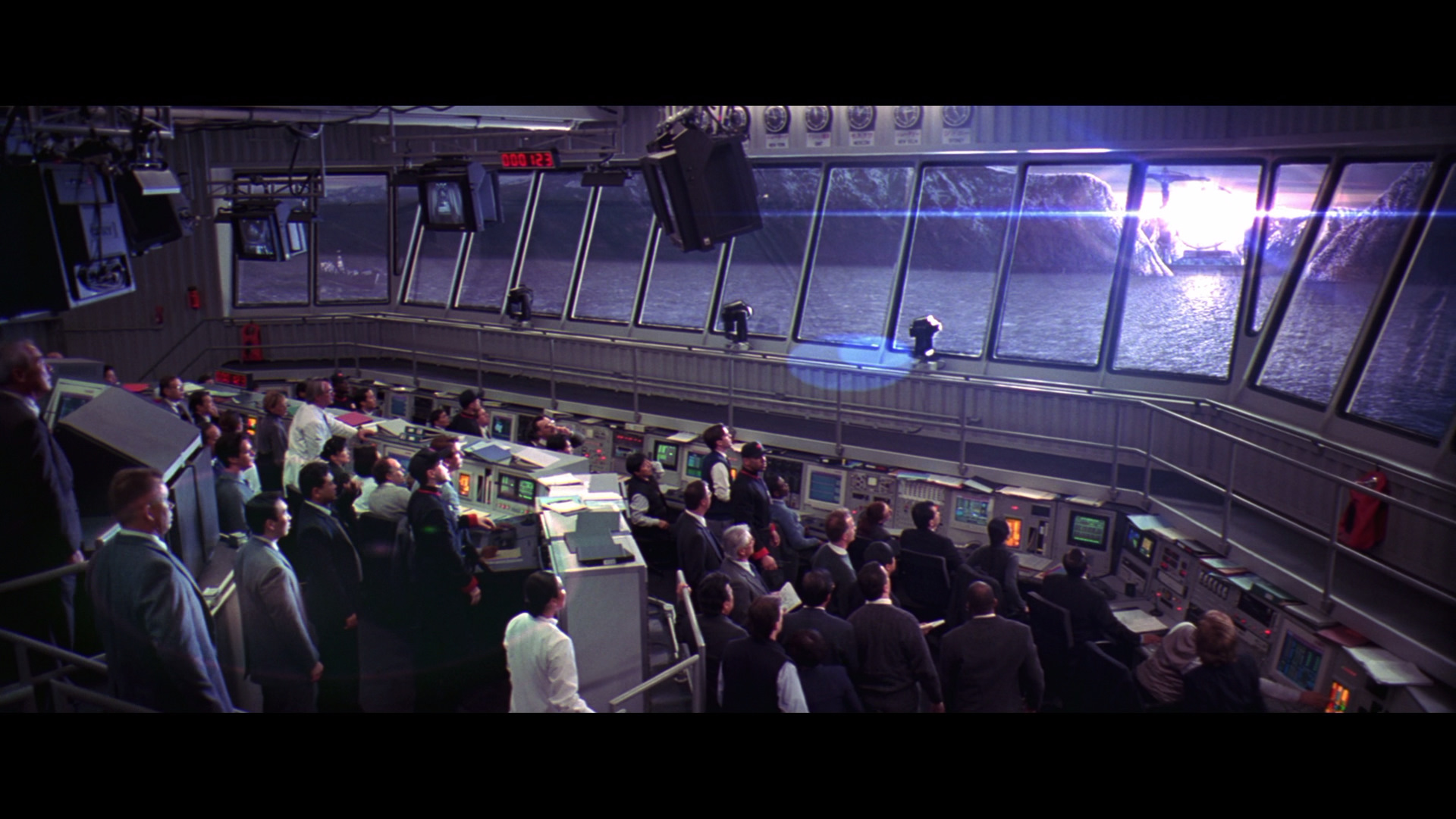

Contact

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by James V. Hart, Michael Goldenberg, Carl Sagan, and Ann Druyan

With Jodie Foster, Matthew McConaughey, James Woods, John Hurt, Tom Skerritt, Angela Bassett, and Rob Lowe.

Barry Sonnenfeld’s Men in Black and Robert Zemeckis’s Contact, both about the existence of extraterrestrials, are probably the first two blockbusters of the summer worthy of the name, even if many grains of salt are required to make much of a meal of either. I’m not claiming that Contact and Men in Black offer the only genuine chills and thrills around — I caught up with The Lost World: Jurassic Park a couple of weekends ago and enjoyed it more than its predecessor — only that they come closer to speaking my language. Given the preordained preeminence of Spielberg’s romp, I’m sure I would have slammed The Lost World, like most of my colleagues, if I’d seen it when they did. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 4, 2004). — J.R.

The Day After Tomorrow

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Roland Emmerich

Written by Emmerich and Jeffrey Nachmanoff

With Dennis Quaid, Jake Gyllenhaal, Ian Holm, Emmy Rossum, Sela Ward, Dash Mihok, Kenneth Welsh, Jay O. Sanders, Austin Nichols, and Perry King.

Roland Emmerich’s latest summer blockbuster is an exceptionally stupid movie. Of course the consensus is that summer blockbusters, even ones that come out in the spring, are supposed to be stupid. But occasionally a summer blockbuster is also expected to offer some food for thought. The Day After Tomorrow, the latest big-budget SF disaster flick, broaches — or stumbles over — the issue of global warming, or what I prefer to call Bush weather, a topic that’s surely worthy of some reflection.

Al Gore declared that this movie was at least an honest fiction about global warming — unlike the fictions about the subject emanating from the White House. Using a stupid movie to call attention to a serious problem put him in a less-than-dignified position, but if he hadn’t tied his arguments to a stupid movie the news media might well have ignored him.

When JFK came out in 1991, all of a sudden, decades after the event, the New York Times and other papers decided the assassination of John F. Read more

Originally posted on July 7, 2013. — J.R.

IL CINEMA RITROVATO

DVD AWARDS 2013

X edition

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti, and Jonathan Rosenbaum, chaired by Peter von Bagh

Because we were faced this year with an embarrassment of riches, we adopted a few new procedures. Apart from creating three new categories for awards, we more generally selected eleven separate releases that we especially valued and only afterwards selected particular categories for each of our choices. We also decided to forego our usual procedure of including individual favorites because doing so would have inflated our choices to seventeen instead of eleven, which is already two more than we selected last year.

Our first new category is the best film or program at this year’s edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato that we would most like to see released on DVD or Blu-Ray. Our selection in this case is the French TV series Bonjour Mr Lewis (1982) by Robert Benayoun. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 15, 1990).

Regarding Peter Biskind’s hyperbolic overestimation of Beatty, then and now — matched in a way by Beatty’s own jokey comparison of Biskind to Trotsky, as reported by Biskind in his recent and sometimes unwittingly hilarious Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America (2010) — it seems that this has only grown over the past 20 or so years. In his Introduction, Biskind rhetorically asks, “how many defining motion pictures does a filmmaker have to make to be considered great?” and then rhetorically answers, “very few,” going on to assign only one or two each to Welles, Renoir, and Kazan, and just one to Peckinpah, but no less than five to Beatty, evidently regarding Bugsy as a towering achievement alongside such trifles as The Magnificent Ambersons, French Cancan, or Wild River. But this is the same writer who can call Kaleidoscope “James Bond lite,” allowing one to ponder what he might actually regard as James Bond heavy — or even as James Bond normal. — J.R.

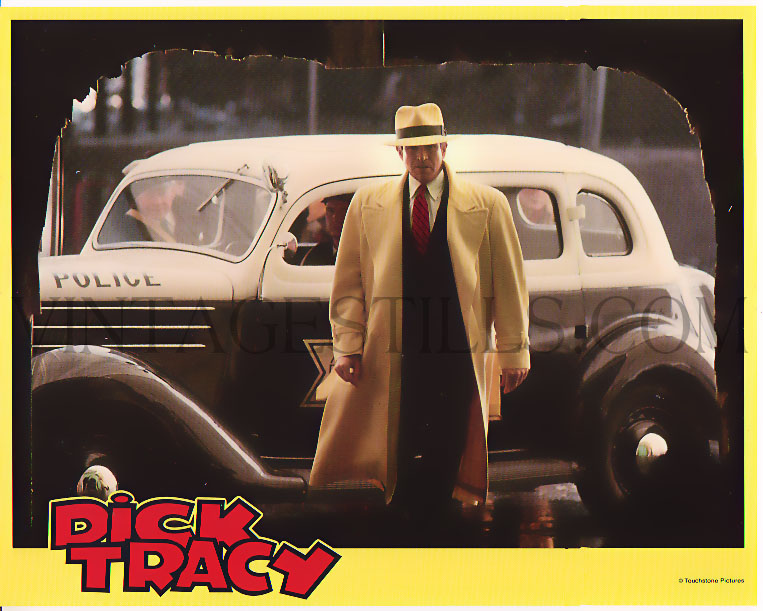

DICK TRACY ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Warren Beatty

Written by Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr.

With Warren Beatty, Charlie Korsmo, Glenne Headly, Madonna, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, William Forsythe, and Charles Durning. Read more

What distinguishes the criminal indictment of Trump in Georgia from his three preceding indictments is its finally forcing the media to call the man a gangster via its repeated use of the term “racketeering”. This brings us, at long last, to the basic ground level of understanding and acknowledging held by Americans in the 1920s who had the clear sight and honesty to call Al Capone a crook, meanwhile implicitly or explicitly dubbing him the king of Chicago. But why has it taken our media this long to call a former President a crook? It seems that more Americans today believe in him as their public servant than 20s Americans thought the same about the mobsters in their midst, although I might be wrong about making this assumption. Either way, the 20s crowd was way ahead of us in acknowledging their own living conditions. And in appreciating them: Capone cared about culture (e.g. opera) whereas the Donald can only succeed if or when he makes us meaner and uglier.

Read more