From the Chicago Reader (June 10, 2005). — J.R.

It seems like hardly anyone in the U.S. ever saw Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle, despite its enormous success elsewhere, apparently not so much because kids had trouble with it as because of the adult suits handling it. But Roger Ebert gave this film only two and a half stars while assigning Mr. and Mrs. Smith three stars the same week (June 10, 2005), suggesting that one of us was probably wrong — or maybe just that Japanese kids and I are both helplessly out of touch with the American mainstream as defined by some grown-ups. — J.R.

Howl’s Moving Castle

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and Written by Hayao Miyazaki

With the voices of Jean Simmons, Christian Bale, Lauren Bacall, Blythe Danner, Emily Mortimer, Josh Hutcherson, and Billy Crystal

The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Robert Rodriguez

Written by Rodriguez and Racer Rodriguez

With Cayden Boyd, Taylor Dooley, Taylor Lautner, George Lopez, Jacob Davich, David Arquette, and Kristin Davis

Mr. and Mrs. Smith

no stars (Worthless)

Directed by Doug Liman

Written by Simon Kinberg

With Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Vince Vaughn, Adam Brody, Kerry Washington, and Keith David

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Sometimes movies earmarked for kids are a lot more nuanced, sophisticated, and mature than the ones that are allegedly for grown-ups. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 20, 1994). — J.R.

Chantal Akerman’s haunting 1993 masterpiece documents without commentary or dialogue her several-months-long trip from east Germany to Moscow — a tough and formally rigorous inventory of what the former Soviet bloc looks and feels like today. Akerman’s painterly penchant for finding Edward Hopper wherever she goes has never been more obvious; this travelogue seemingly offers vistas any alert tourist could find yet delivers a series of images and sounds that are impossible to shake later: the countless tracking shots, the sense of people forever waiting, the rare occurrence of a plaintive offscreen violin over an otherwise densely ambient sound track, static glimpses of roadside sites and domestic interiors, the periphery of an outdoor rock concert, a heavy Moscow snowfall, a crowded terminal where weary people and baggage are huddled together like so many dropped handkerchiefs. The only other film I know that imparts such a vivid sense of being somewhere is the Egyptian section of Straub-Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late. Everyone goes to movies in search of events, but the extraordinary events in Akerman’s sorrowful, intractable film are the shots themselves — the everyday recorded by a powerful artist with an acute eye and ear. Read more

A response to a poll, from Sight and Sound (January 2007). – J.R.

In order to write briefly about five films that I first saw in 2006 that are especially important to me, I have to violate a taboo against acknowledging works that aren’t (yet) readily available. More specifically, the first two on my list haven’t yet been seen very widely outside of film festivals and/or the countries where they were made, while the last two, even more rarefied, have only been shown under special circumstances, in both cases because their filmmakers are under no commercial pressures to release them and would like to oversee and monitor their exhibition. Although I’m aware that this may irritate some readers, I’d rather address them like adults than succumb to the infantile consumerist model of instant gratification, according to which works should be known about only when they can be immediately accessed. After all, some pleasures are worth waiting for.

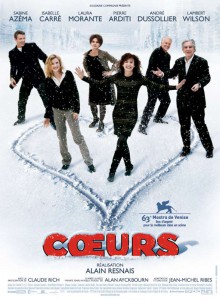

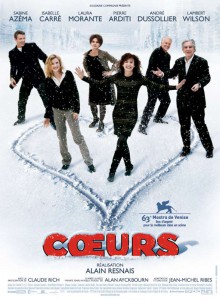

Coeurs

Alain Resnais’ dark, exquisite, and highly personal adaptation of Alan Ayckbourn’s Private Fears of Public Places, which I saw at film festivals in Venice and Toronto, is eloquent testimony both to how distilled his art has become at age 84 and how readily Ayckbourn’s examples of English repression can be converted into French equivalents. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1993). — J.R.

Aiming successfully for a wider audience in 1961, the neglected French independent Jean-Pierre Melville (Les enfants terribles, Le samourai) adapted Beatrix Beck’s autobiographical novel, set in a French village during World War II, about a young woman falling in love with a handsome, radical young priest who’s fully aware of his power over her. For the starring roles Melville, godfather of the New Wave, ironically selected two talented actors catapulted to fame by that movement — Hiroshima, mon amour‘s Emmanuele Riva and Breathless‘s Jean-Paul Belmondo. The poetic results are literary and personal; the heroine’s offscreen narration suggests the pre-Bressonian form of Melville’s first feature, Le silence de la mer, and sudden subjective shots convey the woman’s physical proximity to the priest as she undergoes an ambiguous religious conversion. Not an unqualified success, the film remains strong for its performances, its inventive editing and framing, and its evocative rendering of the French occupation. According to Melville, the film ran for 193 minutes in its prerelease form; he edited out 65 minutes, and another 18 minutes are missing from the present version. The eclectic and resourceful nonjazz score is by jazz pianist Martial Solal. Read more

From the November 1, 1993 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

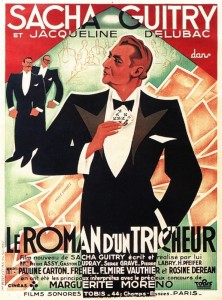

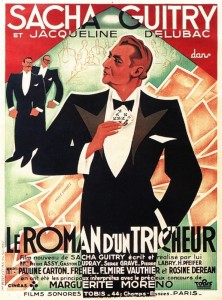

Widely regarded as Sacha Guitry’s masterpiece (though I’d place it below The Pearls of the Crown), this 1936 tour de force can be regarded as a kind of concerto for the writer-director-performer’s special brand of brittle cleverness. After a credits sequence that introduces us to the film’s cast and crew, Guitry settles into a flashback account of how the title hero learned to benefit from cheating over the course of his life. A notoriously anticinematic cineaste whose first love was theater, Guitry nevertheless had a flair for cinematic high jinks when it came to adapting his plays (or in this case a novel) to film, and most of this movie registers as a rather lively and stylishly inventive silent film, with Guitry’s character serving as offscreen lecturer. Francois Truffaut was sufficiently impressed to dub Guitry a French brother of Lubitsch, though Guitry clearly differs from this master of continental romance in that his own personality invariably overwhelms his characters. In French with subtitles. 85 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1993). — J.R.

Some of my colleagues criticized this Philip Kaufman cop movie for softening the anti-Japanese feeling of the Michael Crichton novel it adapts — for coming down on corporate capitalism in general more than Japanese capitalism in particular, and diluting or at least complicating the racial implications by making the principal hero black instead of white. But I found it pretty entertaining, as well as provocative in some of its comments about contemporary life. Just about everyone — including Wesley Snipes and Sean Connery as a couple of LA cops uncovering a business conspiracy while investigating a murder — turns out to be somewhat corrupt, and the Connery character’s pithy explanations for the cultural and behavioral differences between the Japanese and American characters help to ameliorate some of the traces of xenophobia that remain. I’d rather see Kaufman upgrading the hackwork of Crichton than degrading the good work of Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers) or Milan Kundera (The Unbearable Lightness of Being). While most of the opportunities to make this a first-rate thriller are wasted, it’s still a pretty good second-rater. Written by Kaufman, Crichton, and Michael Backes; with Harvey Keitel, Cary-Horoyuki Tagawa, Mako, Ray Wise, and Tia Carrere. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1994). — J.R.

This 1993 film by the eclectic and talented Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf (The Peddler, Marriage of the Blessed) is a contemporary semitragic farce about a burly film actor who wants to act only in art films but is forced by his family’s economic demands to do a string of trashy commercial movies. His tormented wife, infertile and obsessed with having a baby, insists that her husband marry and impregnate a second wife, a deaf-mute Gypsy, to provide them with a child. What keeps this picture frenetic, apart from the hysterical action and satirical treatment of the Iranian media, is the couple’s surreal, high-tech home and Makhmalbaf’s hyperbolic, eccentric mise en scene, which fit together hand and glove (as they were undoubtedly designed to do). The three lead actors — Akbar Abdi (playing some version of himself), Fatemeh Motamed Aria, and Mahaya Petrossian — were all in Once Upon a Time, Cinema, Makhmalbaf’s previous feature; there appear to be some cross-references (such as the hero’s Chaplin worship), but here the tone is more caustic, the inventiveness more pointed. The meanings of both films are less than entirely clear, but my hunch is that each is a comic allegory about the rift between traditional and contemporary Iran, in which class differences and cultural differences are equally pertinent. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 24, 1993). — J.R.

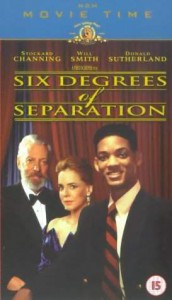

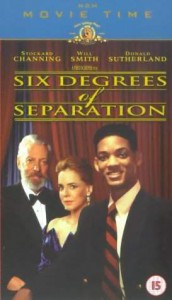

A young hustler (Will Smith) claiming to be the son of Sidney Poitier cons his way into the upper-class Manhattan household and affections of a middle-aged couple (Stockard Channing and Donald Sutherland), with disquieting and soul-searching consequences once his fraud is discovered. John Guare adapted his own play by transplanting the action from a bare stage to a variety of realistic locations, most of them in Manhattan, and has fortunately (and daringly) retained the highly theatrical language of the original. Fred Schepisi’s razor-sharp direction makes it both sing and soar as it explores some of the social gulfs and philosophical crevices that define contemporary urban life. The movie basically belongs to Channing, who gives it both moral force and heat, but with an audacious lesson in making the theatrical cinematic Schepisi does a superb job as well. Fine Arts.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1993). — J.R.

As in Rambling Rose, director Martha Coolidge does an interesting and effective job here of reinterpreting from a woman’s perspective autobiographical and nostalgic material written by a man. This time the material is an adaptation by Neil Simon of his own play about living for a spell in Yonkers in 1942 (Brad Stoll plays the narrator-protagonist at age 15) with his younger brother (Mike Damus), bitter and tyrannical grandmother (Irene Worth), and wacky aunt (Mercedes Ruehl), while his widowed father (Jack Laufer) struggles in the south to pay off some debts. Ironically, the movie comes into its own only in scenes from which the teenage hero is absent; the rest of the time it is charming Simon material without much staying power. Richard Dreyfuss plays a criminal uncle who briefly hides out with the family and David Strathairn’s a slow-witted movie theater usher the wacky aunt wants to marry. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 1993). — J.R.

If what you know about this exuberant, self-regarding movie comes from its countless inferior imitations (from Mazursky’s Alex in Wonderland and The Pickle to Allen’s Stardust Memories to Fosse’s All That Jazz), you owe it to yourself to see Federico Fellini’s exhilarating, stocktaking original — an expressionist, circuslike comedy about the complex mental and social life of a big-time filmmaker (Marcello Mastroianni) stuck for a subject and the busy world surrounding him. It’s Fellini’s last black-and-white picture, and conceivably the most gorgeous and inventive thing he’s ever made — certainly more fun than anything he’s made since. (The only other Fellini movie that’s about as pleasurable would be The White Sheik.) With Claudia Cardinale, Sandra Milo, and Anouk Aimee (1963). A new 35-millimeter print will be shown. Music Box, Friday through Thursday, May 7 through 13.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 26, 1996). — J.R.

Like its predecessors, the concluding and entirely self-sufficient feature in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s epic trilogy about the history of Taiwan in the 20th century — a landmark in Taiwanese cinema along with Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day — focuses on a specific period and a specific art form. City of Sadness (1989) covers the end of World War II through the retreat of the Kuomintang to Taiwan in 1949 and concentrates on still photography; The Puppet Master (1993) covers the first 36 years (1909-1945) in the life of puppet master Li Tien-lu and showcases his art. This film, whose art form is cinema itself, intercuts material from 1949 to the present. In the present a young film actress preparing to play Chiang Bi-yu — an anti-Japanese guerrilla in 40s China who, along with her husband, was arrested when she returned to Taiwan during the anticommunist “White Terror” of the 50s — is harassed by an anonymous caller who’s stolen her diary and is faxing her pages from it. Images evoked by her diary from her past as a drug-addicted barmaid involved with a gangster alternate with her imaginative projections of the film she’s about to shoot, seen in black and white. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 16, 1993). — J.R.

The late Sergei Paradjanov’s greatest film, a mystical and historical mosaic about the life, work, and inner world of the 18th-century Armenian poet Sayat Nova, has previously been available only in the ethnically “dry-cleaned” Russian version — recut and somewhat reorganized by Sergei Yutkevich, with chapter headings added to clarify the content for Russian viewers. This superior version of the film, recently found in an Armenian studio, shouldn’t be regarded as definitive (some of the material from the Yutkevich cut is missing), but it’s certainly the finest we have and may ever have: some shots and sequences are new, some are positioned differently, and, of particular advantage to Western viewers, much more of the poetry is subtitled. (Oddly enough, it’s hard to tell why the “new” shots were censored.) In both versions the striking use of tableaulike frames recalls the shallow space of movies made roughly a century ago, while the gorgeous uses of color and the wild poetic conceits seem to derive from some utopian cinema of the future, at once “difficult” and immediate, cryptic and ravishing. This is essential viewing (1969). Facets Multimedia Center, 1517 W. Fullerton, Friday and Saturday, July 16 and 17, 7:00 and 9:00; Sunday, July 18, 5:30 and 7:30; and Monday through Thursday, July 19 through 22, 7:00 and 9:00; 281-4114. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 3, 1993). — J.R.

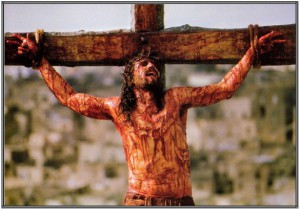

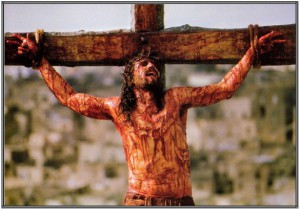

Despite the title, I assumed this drama about the last 12 hours of Jesus’s life would include something about his teachings, at least in flashback. But the Sermon on the Mount is reduced to two sound bites, and miracles and good works barely get a glance; director Mel Gibson stresses only cruelty and suffering, complete with slow motion and masochistic point-of-view shots. The charges of anti-Semitism and homophobia hurled at the movie seem too narrow; its general disgust for humanity is so unrelenting that the military-sounding drums at the end seem to be welcoming the apocalypse (rather like the mass slaughter following the Mexican rebel’s torture in The Wild Bunch). If I were a Christian, I’d be appalled to have this primitive and pornographic bloodbath presume to speak for me. With James Caviezel, Maia Morgenstern, Monica Bellucci, and Hristo Naumov Shopov; Benedict Fitzgerald (Wise Blood) collaborated with Gibson on the script. In Aramaic, Latin, and Hebrew with subtitles. R, 127 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1993). — J.R.

Paul Mazursky’s umpteenth remake of 8 1/2, which only goes to show that if you keep imitating the same movie you’re bound to get progressively staler, not fresher. And unlike such brittle 8 1/2 imitations as All That Jazz and Stardust Memories, this one starts out mushy and gets softer and softer as it develops. The story covers about 36 hours in the life of celebrated writer-director Harry Stone (Danny Aiello) after he arrives in New York from Paris for the preview of his new picture, a teen fantasy called The Pickle that he considers a sellout and fears will be a flop. Before long, we also meet his longtime agent (Jerry Stiller), 22-year-old French girlfriend (Clotilde Courau), and several relatives or ex-relatives (“I’m your ex-wife, Ellen,” Dyan Cannon announces to him and the camera at a surprise party, just in case he or we don’t remember.) Periodic black-and-white cutaways to Stone’s Jewish childhood in Brooklyn and clips from his new color movie show off cinematographer Fred Murphy’s talents much more than Mazursky’s, whose wit seems to have deserted him almost entirely; the final impression is much closer to Jaglom’s Venice/Venice than to Fellini. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 16, 1993). — J.R.

EL MARIACHI

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Robert Rodriguez

With Carlos Gallardo, Consuelo Gomez, Peter Marquardt, Jaime De Hoyos, and Reinol Martinez.

I was several weeks late catching up with El mariachi, a fine little action picture in Spanish that’s been playing at the Water Tower (and opens this week at the Biograph and Bricktown Square). Judging from all the reviews and press stories I read beforehand, an essential part of the movie’s meaning — almost treated as if it were part of the plot — is that its 24-year-old writer-director, Robert Rodriguez, made it for $7,000 and, now a client of Hollywood’s International Creative Management agency, has a two-year contract with Columbia Pictures, the movie’s distributor, that includes plans to shoot a $6 million English-language remake. Much less important, it would seem, is the fate of the movie’s title hero (played by Carlos Gallardo, also Rodriguez’s coproducer). All he ever wanted, “el mariachi” makes clear, is to be a folk musician like his ancestors, though he loses his guitar, the use of one hand, his music, his girlfriend, and possibly even his soul in the process of saving his skin, which entails becoming a successful killer and appropriating the Anglo villain’s weapons. Read more