If I’d had to depend entirely on the quality and interest of the films released in any given week, I probably wouldn’t have remained a movie reviewer for several decades. Luckily, I often found ways of writing about other topics, using the film or films being released as excuses. This was especially true during my extended stint of writing for Soho News almost every week for about about a year and a half (1979-1981), reviewing books (mainly fiction and literary criticism) as well as movies, and during my more than twenty years of writing about films for the Chicago Reader, I usually had the same freedom, at least as long as I had a fair amount of length at my disposal. Perhaps the most obvious example of this freedom at Soho News was the following piece about Mad that I did in 1980, for the July 16 issue, occasioned by a very forgettable comedy released that week. — J.R..

A Fond Madness

Though the ads for the crude, uneven Up the Academy are at some pains to link the movie to Mad — a publication (first a comic book, then a magazine) –- now in its 28th year, the connection clearly has more to do with packaging than with contents. Like the Star Trek “meals” you could purchase at McDonald’s last winter, or the entrepreneurial spirit that continues to invent such anomalous items as Donald Duck grapefruit juice, it bears all the earmarks of a promotion gimmick that plays merry havoc with existential and ontological identities. The apparent logic is to duplicate at least the packaging principles of Animal House, which had its own dubious linkups with National Lampoon. But even the preteens who read Mad will know they’ve been tricked.

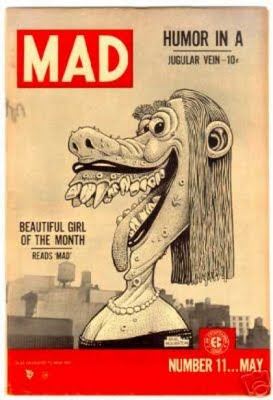

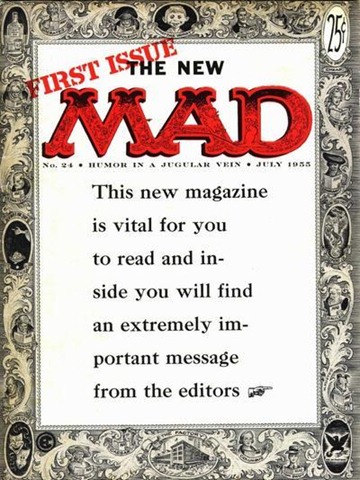

A half-human piece of pasteboard usually designated as Alfred E. Neuman — and labeled Alfred E. Weinberg, founder of Weinberg Military Academy, in the ads — is trotted out at the beginning and end, furnished with a comic-strip bubble that says, “What, me worry?” and afforded a couple of stiff marionette gestures. This more or less exhausts the producers’ responsibility to Mad readers, past and present; yet even as a substitute for nothing, it’s pretty bogus. This is particularly true for an old fan of the comic book like myself, who wasn’t introduced to Alfred E. Neuman until the mid-‘50s — around the same time that the comic book became a magazine, and the first Mad paperbacks started appearing — and who considers him a symbol of Mad’s decline rather than its essence.

***

The old Mad was a central reference point in my preteen environment, but it didn’t spring full-blown from a void. By the time I was first exposed to it at a Jewish camp in Maine, during the summer of ’53 when I was 10, I’d already discovered Jerry Lewis in My Friend Irma in 1949, attended a live concert of Spike Jones in ’51, thrilled to a brutally hilarious Western takeoff called Skipalong Rosenbloom the same year, and first encountered Son of Paleface in ’52 — to mention just a few related enterprises.

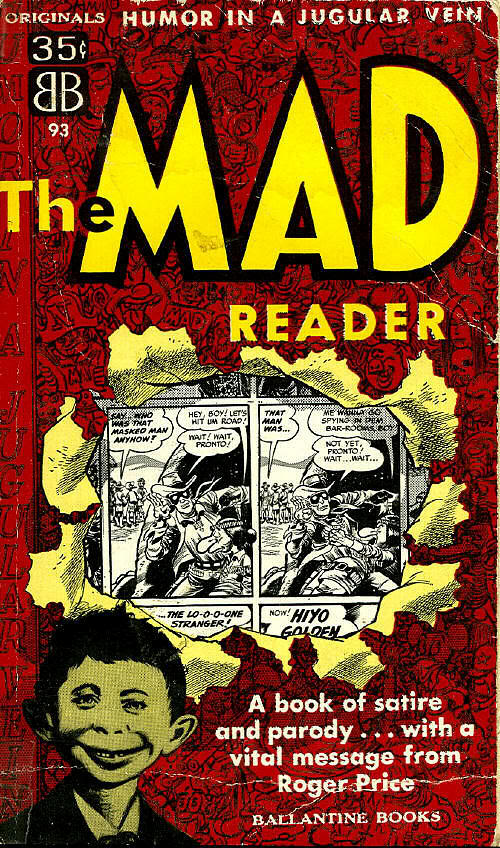

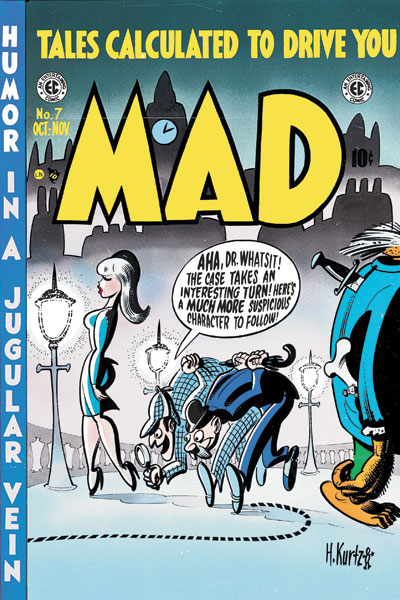

The aesthetic impression made on me by Mad in ’53 could be called deceptively auteurist. I was acutely aware of the styles of individual artists who drew (and, I assumed, wrote) the stories, but only dimly conscious of the role played by Harvey Kurtzman -– who, along with publisher William Gaines, invented Mad the year before. According to Roger Price’s preface to The Mad Reader, Jack Davis, Wallace Wood, and Bill Elder (my favorite) were essentially gifted metteurs-en-scène who executed Kurtzman’s designs, but that wasn’t the way I understood it at the time.

Less ambiguous was Mad’s overall ethnic thrust –- explicitly New York working-class-Jewish in nearly all its comic pet phrases and emblems (like furshlugginer, Potzrebie, chicken fat, and halavah), ferociously aggressive in its sex, its violence, its hyperventilated maverick goofiness, and its virtual lust for defying every taboo in sight. As Donald Phelps was later to observe of the magazine, “Both the humor and the sheer awfulness of Mad — which are inseparable -– depend on the intimate response of the New Yorker to the wastefulness with which he comes in direct or indirect contact every day: the scraps of discarded food which adorn the street -– New York’s insignia ought to be a half-eaten pizza lying on the sidewalk…” An aesthetics, in short, of garbage, which Phelps called “The Muck School”. More honest about its own obscenity than, say, Scrooge McDuck diving through his mountains of coin, Mad’s perverse humor was like a weekend with Henry Miller after a year with Ronald Reagan.

Alfred E. Neuman was never a true emblem of this irreverence because he was finally too respectable and domesticated a representative of that world: a harmless, ugly bar mitzvah boy with a shit-eating grin and potato-chip ears –- not a disgruntled adult howling for blood, which is what the raunchy comic book more often reflected.

Up the Academy is no Zéro de conduite, but some of the anarchic impulse of the old Mad is at least fitfully suggested. One can’t, however, really compare the social impacts of the old Mad and the new movie, because the contexts are much too different. The homophobic gags with the dance instructor can’t be said to violate a taboo in the same way that a parody of Archie and Jughead as repulsive creeps with switchblades functioned in the ‘50s. Even if the gags had been progay, they still couldn’t function as a transgression in the way that Mad once could (and did).

***

In June 1954, Robert Warshow’s “Paul, the Horror Comics, and Dr. Wertham” appeared in Commentary — a very thoughtful consideration of E.C. Comics (which included Tales from the Crypt, Shock SuspenStories, and Panic, as well as Mad), specifically in relation to Warshow’s 10-year-old son, Paul, and himself, and to the controversy stirred up by Dr. Fredric Wertham’s lurid polemic against comics, Seduction of the Innocent ( a perfect Cold War title, evoking Whittaker Chambers and J. Edgar Hoover). My father read the Warshow essay and, precocious little twerp that I was, I read it too — even though it was written for my father just as unequivocally as Mad was produced for me. Warshow was right to call the Wertham book “a kind of crime comic book for parents”: on a trip to Birmingham [Alabama], my father and I came across a copy in a bookstore and we both looked at the frightening illustrations of comic book violence with the same sort of seedy fascination we might have had for pornography.

No question about it: E.C. Comics were grizzly and kinky (which eventually led to the comic-book equivalent of a Hays Office, issuing seals of approval to practically everyone except E.C.) That’s what made them so exciting and attractive — and what makes a sodden lump like Neuman, and the more sober, glib, and formula-ridden magazine that this character-emblem ushered in, cold potatoes by comparison.

“What, me worry?” indeed! In the final analysis, Neuman insulted and circumscribed the disaffected, alienated Mad audience simply by defining it in market terms and then exploiting it like a tobacco company, which enabled Mad to become big business. (Present circulation is 1.8 million, over five dozen paperback collections are in print, and Parker Brothers sold a million Mad board games last year.)

***

An interesting enigma: Why did most adults have so much contempt for Jerry Lewis and Mad in the ‘50s? How much of that tension was generational? Could it be that, even before rock ‘n’ roll, a certain kind of humor was already declaring the independence of one generation and culture from another? It’s easy to forget that in the early ‘50s, the form of this humor could be avant-garde. The Spike Jones concert I’d attended was a mixed-media happening avant la lettre, and for an exciting period, Mad Comics came out with a completely different cover every issue, so different that one had trouble finding it on the racks. (Each cover would mock a new adult totem: Picasso, The Saturday Evening Post, racing forms, the Mona Lisa — or the ugly school notebooks that grownups would force on helpless kids.)

Warshow, who was already hip to the relationship of Mad to Jerry Lewis and Spike Jones (as well as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges), aptly noted that “The tendency of the humor, in its insistent violence, is to reduce all culture to indiscriminate anarchy.” (On ’50s TV, Sid Caesar and Ernier Kovacs were the main exponents of this principle.) The final page of “Famous Family Album Rejects,” a feature in the current July issue of the magazine, gives us would-be childhood snapshots of Terry Savalas, Julia Child, Albert Einstein, Bert Lance, Ralph Nader, and Henry Kissinger — a typical instance of the process whereby every disparate cultural icon becomes equal under the democratic, jeering gaze of “Muck School” humor.

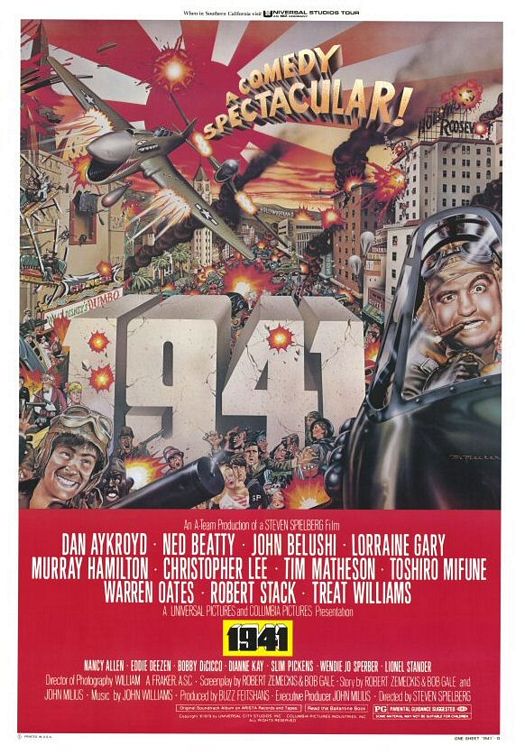

Mad Comics did this too, and so does the recent movie 1941 — which can largely be read as an homage to the spirit of Mad, above all in its fixed, sneering stance in relation to the action. (In relation to parody, too, the movie has the same dogged one-upmanship — the kind which says, “I can do a period dance hall sequence better than New York, New York, a more slam-bang special effects space chase than the one near the end of Star Wars, a snazzier opening than Jaws, etc.)

While the politics of Mad has always been more or less defeatist, the last two issues of the magazine virtually institutionalize this position in separate features. “Election Year Jabberwocky” (July) and the “Vote Mad/Alfred E. Neuman for President” cover of the September issue both line up all the obvious candidates — with the curious absence of John Anderson in each case — and treat them to the same homogenizing process undergone by Savalas, Einstein & Co. in “Fabulous Family Album Rejects”.

***

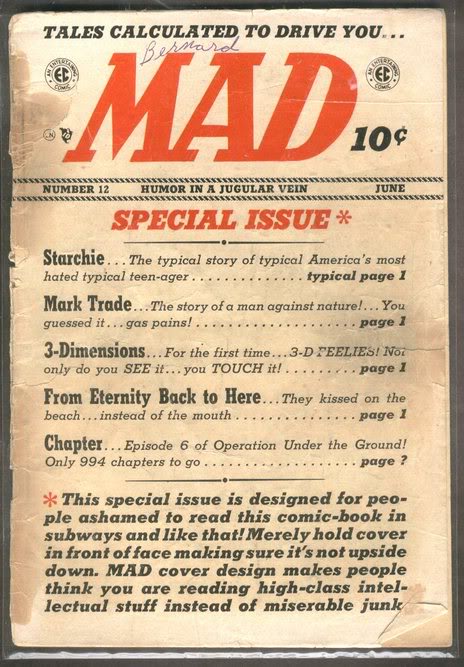

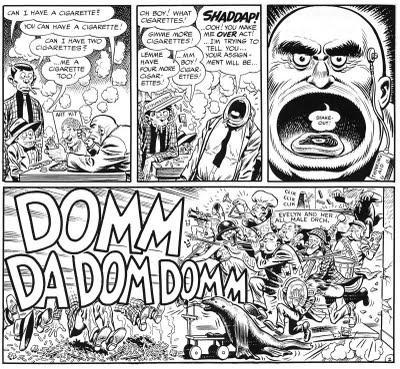

A further example of Mad‘s avant-gardism, and one still clinging like barnacles to the magazine, is its frequent references to its own formal properties (and those of the media it parodies), a technique identified by Russian formalist critic Viktor Shklovsky as “baring the device”. Countless examples from the comic could be cited: in “Starchie,” attention is directed to the fact that the faces of both heroines, Biddy and Salonica, are drawn identically. In a Robinson Crusoe takeoff, the title hero tears off part of the frame of the comic-book square he’s inside when he needs a straight line for a ruler. “Dragged Net,” a very funny analysis of the old TV show, concentrates on the dramatic use of its booming theme song and other structural devices.

The same general tendency is evident in recent issues of the magazine. “Star Bleech — The (Gacck!) Motion Picture” (July) features such exchanges as, “She’s — she’s some kind of ROBOT!!” “At least SHE has an EXCUSE for her acting! What’s YOURS?” Better yet, James Garner’s father in “The Crockford Files” (September) remarks at one point that “It’s this INFLATION, Sonny! Why, this crummy magazine WE’RE in costs 75¢!” Unfortunately, the artwork is much less dynamic or interesting than that in any of my ’50s examples.

***

Robert Warshow was about 37 when he wrote about Mad, the same age I am now. Unlike Warshow, I have no kids, so if I take a parental position about preteens reading Mad, this has to be toward myself in the early ’50s. What kinds of residue did the original Mad leave? Some traces of adolescent whimsy that tend to juice up my writing like chicken fat (with comparable caloric excess); a hatred for the corporate languages of mass media; a certain taste for the giddy sensation of sudden distance from an artwork created by “baring the device”; and a hysterical, puritanical relationship to sex, money, and violence that mixes love and hatred for all three so intricately — as in the movies of Tex Avery, Samuel Fuller, Jerry Lewis, Otto Preminger, Jerzy Skolimowski, and Frank Tashlin — that a volatile, smoky cocktail emerges from the conflict.

— The Soho News, July 16, 1980