From the Chicago Reader (July 9, 2004). — J.R.

Springtime in a Small Town

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Tian Zhuangzhuang

Written by Ah Cheng

With Hu Jingfan, Wu Jun, Xin Baiqing, Ye Xiaokeng, and Lu Sisi.

It’s strange and very telling that the film most highly regarded in the Chinese-speaking world –especially in Hong Kong and Taiwan — is hardly known outside China. Fei Mu’s 1948 Spring in a Small City, as it’s usually called in English, is a film I doubt I ever would have seen if a Chinese friend hadn’t sent me a subtitled copy taken from a rare showing on SBS, Australia’s state-funded multicultural TV channel, several years ago.

Once I discovered that Fei Mu’s black-and-white film lives up to its reputation, I mentioned it casually to a local Chinese film buff, who told me it was readily available at the video store he frequents in Chinatown. Why then are English subtitled versions so scarce? After all, the film was a key inspiration for Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), which has been savored by non-Asians across the globe. And Tian Zhuangzhuang’s color remake of Fei Mu’s classic, Springtime in a Small Town (2002), showing this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, is no less accessible. Read more

In late 2002 or early 2003, I was approached by an editor at Oxford University Press about the possibility of editing a new Oxford Companion to Film. Despite some initial reluctance on my part—being rather frightened of the dimensions and demands of such a project—the editor was persistent, and eventually I signed a contract to carry out this work, after drawing up a proposal, enlisting the late Robert Tashman, a Chicago friend (and former Granta editor) to serve as line editor, and compiling several lists of entries (1099 of them covering A through L, as far as I ever got) and contributors (an ideal list of 43). But the project fell aground after the editor who had enlisted me got downsized. A meeting of Tashman and myself with other Oxford editors in New York made it clear that they weren’t interested in following through on the project, and frankly, I wound up feeling relief about this (although I’m sorry to say that Bob was disappointed—even though both of us were able to keep our advances).

What follows are two sample entries that I wrote for this abortive project; if memory serves, both benefited from Bob’s line-editing. I haven’t updated either of them. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 2002). — J.R.

Alexander Dovzhenko’s first color film and last completed feature (1948, 103 min.) was based on his play Life in Bloom, a biography (verging on hagiography) of the celebrated Russian botanist Ivan Michurin. Both the play and its screen adaptation attracted the interest of Joseph Stalin, who dictated various revisions; in fact Dovzhenko may have removed his name from the film in protest, as the credits list his wife, Julia Solntseva, as director and identify him only as the producer and screenwriter. Certain characteristic touches show up here and there — some signature landscapes, a powerful passage evoking John Ford that shows Michurin’s grief over his wife’s death — but generally this is a feel-good Stalinist biopic. Perhaps the most interesting propaganda comes in the opening scene, when a wealthy American (speaking in English) attempts to lure Michurin to the States with untold riches. In Russian with subtitles. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1988). — J.R.

Along with The Man Who Would Be King and The Dead, this is arguably John Huston’s best literary adaptation, and conceivably his very best film — a very close rendering of Flannery O’Connor’s remarkable first novel about a crazed southern cracker (a perfectly cast Brad Dourif) who sets out to preach a church without Christ, and winds up suffering a true Christian martyrdom in spite of himself. The period, local ambience, and O’Connor’s deadly gallows humor are all perfectly caught, and apart from the subtle if highly pertinent fact that this is an unbeliever’s version of a believer’s novel, it’s about as faithful a version of O’Connor’s grotesque world as one could ever hope to get on film, hilarious and frightening in equal measure. O’Connor conceived her novel as a parody of existentialism, and Huston’s own links with existentialism — as the director of the first U.S. stage production of No Exit, as well as Sartre’s Freud script — make him an able interpreter. With Harry Dean Stanton, Amy Wright, Daniel Shor, Ned Beatty, and Huston himself as the hero’s fire-and-brimstone grandfather. The producer is Michael Fitzgerald, whose family’s friendship with O’Connor guaranteed the fidelity and seriousness of the undertaking (1979). Read more

Posted on Artforum’s web site, 12/23/09. –- J.R.

Terry Gilliam’s ambitious fantasy, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, set to open in the US on Christmas Day, already did well in some parts of Europe when it premiered there in October—notably Italy and the UK, where it placed third during its opening weekends in both countries. I saw it the first time myself in Saint Andrews, Scotland, with an appreciative audience in early November. The lead character, Tony — played by the late Heath Ledger and three other actors (Johnny Depp, Jude Law, and Colin Farrell), who were called in when Ledger died halfway through the filming — is partly conceived as a spoof on Tony Blair, though one wonders whether this conceit will register with much clarity for the American audience. But it’s also unclear how much this will matter, given all the other points of attraction (such as Tom Waits as the devil and Christopher Plummer as the Methuselah-like Parnassus). Far more relevant, it seems, is the way Gilliam has ingeniously adapted the avant-garde multiple-casting ploy of everyone from Yvonne Rainer (Kristina Talking Pictures [1976]) to Todd Haynes [2007]) in terms of his own mainstream fantasy plot. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1988). . — J.R.

Whether you like this or not — and it’s quite possible that you won’t — this has got to be one of the weirdest and most original movies around. Written and directed by former film critic and scriptwriter-turned-director Paul Mayersberg (The Man Who Fell to Earth), whose previous solo feature never hit these shores, this is produced by Julie Corman, wife of Roger, and harks back to a lot of 60s Corman productions in various ways, for better and for worse; it also may be the first U.S. exploitation film to show the influence of Raul Ruiz in its striking use of colors and color filters, and Jasper Johns springs to mind in relation to some of the set painting. Mayersberg’s starting point and putative focus is Isaac Asimov’s famous SF story, set on the planet Lagash, where it is always daylight, shortly before its civilization collapses; David Birney, Sarah Douglas, Andra Mylian, and Alexis Kanner head the cast, and much of the action and decor reflect a series of interesting solutions for representing an alien culture as cheaply as possible. If you’re looking for something different, make sure to catch this oddity. Read more

From Time Out (London), June 4-10, 1976. I’ve always had very mixed feelings about this commissioned cover-story piece, especially about its stupid and offensive title (not mine) as well as what I now regard as a certain conformist pandering to what I regarded as mainstream taste. As I recall, the whole piece was written very quickly, following the capricious whim of the magazine’s editor. I especially regret the way I fell into some of the mindless consensus of condemning The Day the Clown Cried without having seen any part of it, which by now has become a standard reflex in Anglo-American Lewis-bashing. I’ve corrected a couple of factual errors. -– J.R.

Who is Jerry Lewis?

A comedian who has acted in over three dozen films, eight of which he’s directed, himself.I became a fan back in 1949, when he first appeared as secondary comic relief in ‘My Friend Irma’, and followed him religiously through his countless vehicles with Dean Martin in the 50s. As I grew older, critics began to warn me that he was childish and self-indulgent, friends groaned whenever his name cropped up, and I discovered that he usually came across as a sanctimonious prig whenever he made personal appearances on TV. Read more

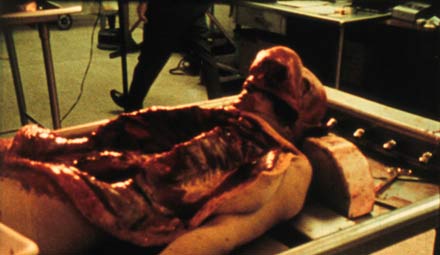

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1988). — J.R.

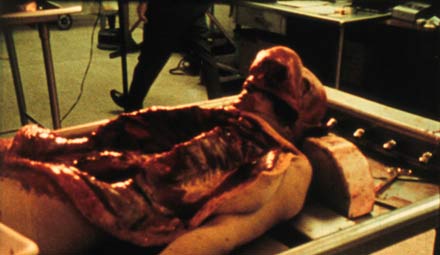

Stan Brakhage’s convulsive personal and silent documentary about a Pittsburgh morgue, made in 1971, is one of the most direct confrontations with death ever recorded on film. Included on the same program — along with a lecture by Chuck Kleinhans, professor of film at Northwestern University — are three other shorts that are not conventionally regarded as horror films, but that will be considered in relation to that genre: Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid’s ground-breaking experimental film Meshes of the Afternoon (1943); Chris Marker’s innovative science fiction film La jetee (1964), which tells its story almost exclusively in stills; and Celia Condi’s 1982 combination of soap-opera characters and dark humor, Beneath the Skin. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 8, 1988). — J.R.

Alain Resnais’ masterpiece, easily his best film in years, is bound to baffle spectators who insist on regarding him as an intellectual rather than an emotional director, simply because he shares the conviction of Carl Dreyer and Robert Bresson that form is the surest route to feelings. In his 11th feature, he adapts a 1929 boulevard melodrama by a forgotten playwright named Henry Bernstein, and holds so close to this “dated” and seemingly unremarkable play that theatrical space and décor — including the absence of a fourth wall — are rigorously respected, and shots of a painted curtain appear between the acts. None of this is done to strike an attitude or “make a statement”: Resnais believes in the material, and wants to give it its due. Yet in the process of doing this, he not only invests the original meaning of “melodrama” (drama with music) with so much beauty and power that he reinvents the genre, but also proves that he is conceivably the greatest living director of actors in the French cinema, and offers a way of regarding the past that implicitly indicts our own era for myopia. (Mélo is certainly a film of the 80s and not an antique, but it may take us another 20 years to understand precisely how and why.) Read more

This was written on February 25, 2007, provoked by yet another case of a Wellesian pseudo-expert bonding with another non-expert to lay down what is supposed to be the definitive history and wisdom on the subject. Sanford Schwartz did write me a short, polite, private response that, as nearly as I can recall, didn’t really engage with any of my arguments. — J.R.

To the Editors:

I’m grateful for Sanford Schwartz’s article about Orson Welles in the March 15 issue of the New York Review of Books, which strikes me as being far more sensitive to Welles’s work and some of the issues posed by his troublesome career than most pieces I’ve read on the subject by nonspecialists. Even if Schwartz’s ideas about Welles as a proto-surrealist are more provocative than convincing to me, they do lead to some arresting observations about his visual style. So I hope he’ll forgive me for pointing out an error in his piece and a few assertions that I believe are misleading. They all derive from confusions that invariably greet any effort made to describe Welles in relatively simple terms.

First, the error: “Although [Welles] was involved with many films that for one reason or another weren’t brought off, he actually finished only twelve, a group that includes the fairly short F for Fake and The Immortal Story, both made for TV.” Read more

From Time Out (London), October 11-17, 1974. –- J.R.

Up to now, Richard Lester has been in the habit of either attacking genres (‘How I Won the War’) or mixing them (‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,’ ‘The Three Musketeers’ –- in the case of ‘A Hard Day’s Night,’ virtually inventing a new genre out of the mixture). In ‘Juggernaut’, a commercial job with relatively modest pretensions, he is simply conforming to a genre -– the Ocean Liner catastrophe –- and comes up with a better-crafted version of ‘The Poseidon Adventure’, complete with multiple subplots and cornball heroics, but with smoother acting and sharper direction. The potential catastrophe is seven steel drums of amatol timed to go off and destroy 1200 passengers unless a ransom is delivered to the mysterious Juggernaut. Using such varied ingredients as the flamboyance of Richard Harris, the stolid inexpressiveness of Omar Sharif and the usual carrying on of Roy Kinnear, Lester milks the situation for all the suspense that can be expected and then some, pushing a few arch gags into the remaining cracks. The results: mindless entertainment of the first order, at least in the Ocean Liner Catastrophe cycle. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1998). — J.R.

Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986) tended to alter his visual style with every film, according to the needs of the story; this 1958 effort is a heavy-duty satire about three competing candy companies trying to outdo one another’s promotional campaigns, and its garish and ugly color photography seems just as functional and deliberate as the beautiful black and white of A False Student and Red Angel. Against a backdrop of hysterical competition and industrial espionage, a slum girl with bad teeth is discovered and transformed into a mascot for one of the candy companies by a cynical porn photographer. The film has rightly been compared to some of Frank Tashlin’s pop-culture comedies, made in Hollywood around the same time, and though it’s probably less funny than Tashlin at his best, its anger is more savage and leaves a more corrosive aftertaste; the apocalyptic ending, for that matter, is worthy of Douglas Sirk. (JR)

Read more

Read more

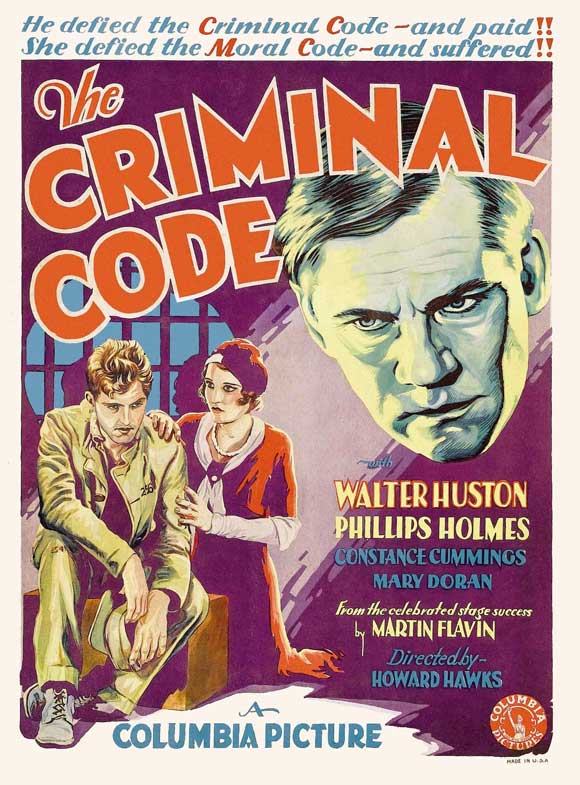

From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1984 (Vol. 51, No. 609). This was published long after I left the MFB staff in early 1977, and by this time, over seven years later, the magazine had finally abandoned its highly dubious practice of restricting all its reviews to single paragraphs. –- J.R.

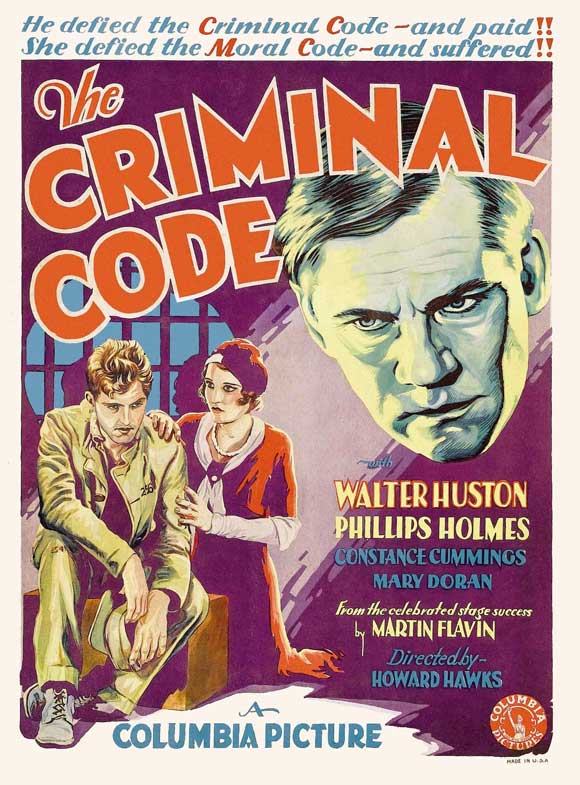

The Criminal Code

U.S.A.,1930

Director: Howard Hawks

Cert–A.dist—Filmfinders. p.c–Columbia. A Howard Hawk production. p–Harry Cohn. sc–Seton I. Miller, Fred Niblo Jnr. Based on the play by Martin Flavin. ph–Teddy Tezlaff, James [Wong] Howe, (uncredited) William O’Connell. ed–Edward Curtiss. a.d–Edward Jewell. m–(not credited). sd. rec–Glenn Rominger. l.p–Walter Huston (Warden Martin Brady), Phillips Holmes (Robert Graham), Constance Cummings (Mary Brady), Mary Doran (Gertrude Williams), De Witt Jennings (Gleason), John Sheehan (MacManus), Boris Karloff (Galloway), Otto Hoffman (Jim Fales), Clark Marshall (Runch), Ethel Wales (Katie), lohn St. Polis (Dr. Rincwulf), Paul Porcassi (Spelvin), Hugh Walker (Lew), Andy Devine (Prisoner), Jack Vance (Reporter), Arthur Hoyt (Nettleford), Nicholas Soussanin, James Guilfoyle, Lee Phelps. 3,245 ft.n90 mins. (16 mm.) Original running time–97 mins. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 2, 1997). — J.R.

An adventurous and sometimes sexy, if only fitfully successful, adaptation of Louise Kaplan’s celebrated nonfiction book by Susan Streitfeld, working with a script she wrote with Julie Hebert (1996). The focus is on the life of a successful single prosecutor (British actress Tilda Swinton, displaying an impeccable American accent) as she waits to discover whether she’s been appointed as a judge, her kleptomaniac-scholar sister (Amy Madigan), the prosecutor’s boyfriend, a lesbian psychotherapist she has a fling with, and other people in her orbit. Oscillating between everyday events in her life and her dreams and fantasies, the film is much more successful with the former than with the latter, which often get heavy-handed and obscure. But the freshness of Streitfeld’s approach toward gender anxiety and social conditioning fascinates even when the overall clarity diminishes. Not for everyone, but those who like it will probably like it a lot. With Karen Sillas, Clancy Brown, Frances Fisher, Laila Robins, Paulina Porizkova, and Dale Shuger. Music Box, Friday through Thursday, May 2 through 8. — Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 2, 1998). — J.R.

Probably the Coen brothers’ most enjoyable movie — glittering with imagination, cleverness, and filmmaking skill — though, as in their other films, the warm feelings they generate around a couple of salt-of-the-earth types don’t apply to anyone else in the cast: you might as well be scraping them off your shoe. The Chandler-esque plot has something to do with Jeff Bridges being mistaken for a Pasadena millionaire, which ultimately involves him as an amateur sleuth in a kidnapping plot. A nice portrait of low-rent LA emerges from this unstable brew, as do two riotous dream sequences. Set during the gulf war and focusing on a trio of dinosaurs — an unemployed pothead and former campus radical (Bridges), a cranky Vietnam vet (John Goodman), and a gratuitous cowboy narrator (Sam Elliott) — this 1998 feature may be the most political Coen movie to date, though I’m sure they’d be the last to admit it. With Julianne Moore, Steve Buscemi, David Huddleston, John Turturro, and Ben Gazzara. R, 117 min. (JR) Read more