From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1984 (Vol. 51, No. 609). This was published long after I left the MFB staff in early 1977, and by this time, over seven years later, the magazine had finally abandoned its highly dubious practice of restricting all its reviews to single paragraphs. –- J.R.

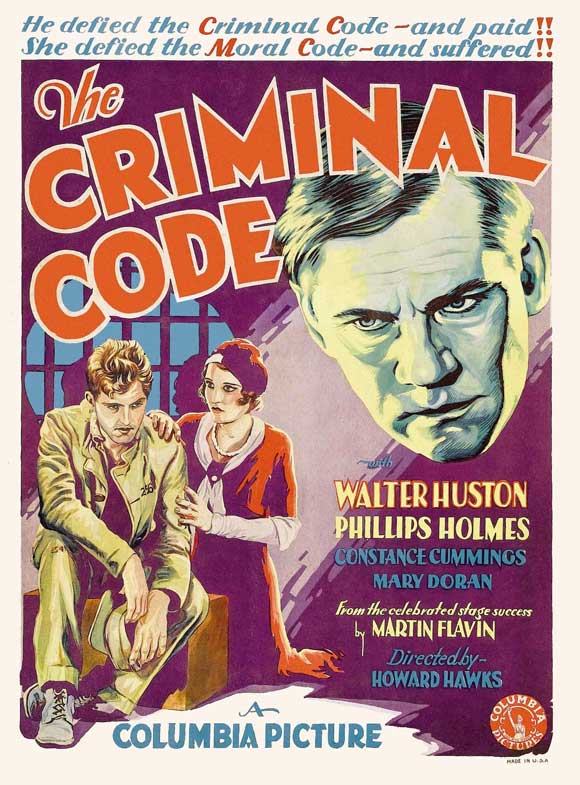

The Criminal Code

U.S.A.,1930

Director: Howard Hawks

Cert–A.dist—Filmfinders. p.c–Columbia. A Howard Hawk production. p–Harry Cohn. sc–Seton I. Miller, Fred Niblo Jnr. Based on the play by Martin Flavin. ph–Teddy Tezlaff, James [Wong] Howe, (uncredited) William O’Connell. ed–Edward Curtiss. a.d–Edward Jewell. m–(not credited). sd. rec–Glenn Rominger. l.p–Walter Huston (Warden Martin Brady), Phillips Holmes (Robert Graham), Constance Cummings (Mary Brady), Mary Doran (Gertrude Williams), De Witt Jennings (Gleason), John Sheehan (MacManus), Boris Karloff (Galloway), Otto Hoffman (Jim Fales), Clark Marshall (Runch), Ethel Wales (Katie), lohn St. Polis (Dr. Rincwulf), Paul Porcassi (Spelvin), Hugh Walker (Lew), Andy Devine (Prisoner), Jack Vance (Reporter), Arthur Hoyt (Nettleford), Nicholas Soussanin, James Guilfoyle, Lee Phelps. 3,245 ft.n90 mins. (16 mm.) Original running time–97 mins.

Bob Graham, a twenty-year-old stockbroker’s clerk, is celebrating his birthday with Gertrude Williams (whom he has just met on the street), when a masher, Parker, makes advances to Gertrude and Graham strikes him with a glass pitcher. Parker dies, and district attorney Martin Brady, after acknowledging Graham’s relative innocence in the episode, argues to Graham’s employer Nettleford that the criminal code dictates that he must pay for the crime anyway.

He is subsequently sentenced to ten years in prison. Six years later: Graham agrees to join his cellmate Jim Fales in a prison break, but Galloway, a third member of the cell serving a twenty-year term, wants to stay in order to avenge himself on the sadistic guard, Gleason, who lost him his parole by reporting an infringement. Brady has meanwhile become the new prison warden, and after Graham, shaken by his mother’s death, suffers a nervous collapse in the jute mill, Dr. Rinewulf urges Brady to give him an easier job. Three months later, Graham is working as Brady’s chauffeur and attracting the interest of his daughter Mary. He backs out of Fales’ escape plan, which is thwarted due to an informer, Runch, and Fales is killed. Runch is kept in Brady’s office for protection, but Galloway, now working as a butler in the adjacent flat, contrives to murder him. Brady puts Graham in solitary confinement to force him to name the killer, until Mary tells her father that she loves Graham and convinces him to become more lenient.

Galloway provokes a guard so that he is sent to solitary confinement himself — in order to prevent Graham from informing — and manages to grab a guard’s gun en route. After Galloway confesses to Brady that he killed Runch and then kills Gleason, order is restored and Graham and Mary are reunited.

The Criminal Code was one of three films made by Howard Hawks in 1930 -– coming after The Dawn Patrol and, apparently, just prior to Scarface (which was released two years later). It remains one of his most neglected films, apart from the memorable clip (Galloway’s stalking pursuit of Runch) seen on TV in Peter Bogdanovich’s 1968 Targets. While it is far from the calibre of Scarface, Hawks’ verve with actors and a sufficiently pungent theme make it a good deal more than a curiosity piece, even if the dreadfully choppy print under review often makes it difficult to tell whether certain plot lacunae (such as the identity of the old woman served tea by Galloway in the flat connected to Brady’s office) should be ascribed to script deficiencies or missing snippets of dialogue. Certainly the script often seems perfunctory or laboured; most notably, Galloway’s labeling of Runch as a “stool pigeon”, followed immediately by the abortive prison break which proves his point, makes for an almost risible QED. But the overall shape and rhythm of the story is a good deal more solid and thoughtful, based on a convincing parallel between the criminal code as propounded separately by Brady and his associate MacManus (“An eye for an eye — that’s the basis for the criminal code — somebody’s got to pay”) and the equally stringent code of ethics adopted by the prisoners, which takes the same position on retribution but the opposite position on informing.

Arguably closer to a film of social protest than any of Hawks’ other work, The Criminal Code benefited from the collaboration of several real convicts. According to one of the interviews in Joseph McBride’s Hawks on Hawks, the director was dissatisfied with the script’s last act. “… [so] I got twenty convicts, got ‘em a room, gave ’em a lunch, gave ’em a drink. I sat down and said, ‘I’m going to tell you guys a story, and I want you to decide how it ends. I’ll go off until you decide. I went off, and they talked for about an hour, and I came in and said, ‘Are you ready to talk?’ and they told me the whole ending, the whole last act . . .” The result is a neat balance between Brady’s patriarchal rectitude and the legitimate grievances of the prisoners themselves — most particularly Graham, but also Fales and even the sinister Galloway; only the informers Gleason (guard) and Runch (convict) register as villains.

Stylistically, The Criminal Code comes across as both a rich exercise in the registers of late silent film (including superimpositions and an almost Langian handling of crowds) and a busy workshop in which many of the director’s subsequent traits are being hammered out. The overlapping dialogue of the opening scene, and the no less characteristic running gag which derives from it (two policemen arguing about their game of pinochle throughout the execution of their routine duties), offer a neat introduction to the film’s acute sense of moral relativity, in which everyone has his or he reasons. (Even Brady, we’re often reminded, has political ambitions, hence ulterior motives for his decisions.) The use of sound, while less experimental than in Sternberg’s Thunderbolt, still seems unusually bold for Hawks, particularly in the obsessively mannerist, repetitive use of the word “yeah” to punctuate practically every speech as well as provide the ground bass for the two noisy prison revolts (actually protests of noise, identified as “yammering” in the dialogue and precipitating the two climactic confrontations between Brady and the convicts).

Set to this ‘music’, the stalking of Runch by Galloway is virtually staged like a ballet, and establishes Karloff’s credentials for playing Frankenstein’s monster with striking prescience. It also sets Karloff’s hulking star persona in place as surely as Hawks’ Monkey Business and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes consolidate the iconic image of Marilyn Monroe.

The dark humour and stark, cartoonish portraiture of Scarface are deftly anticipated in such details as Brady being shaved by a convict “sent up… for cuttin’ a guy’s throat”, while John Wayne rolling cigarettes for Dean Martin in Rio Bravo might be sensed in the gentle way Constance Cummings takes over Phillips Holmes’ peeling of potatoes in their touching kitchen scene — which is merely one gestural beauty among many. Indeed, while most of the acting honours in the The Criminal Code have rightly gone to Huston and Karloff, Holmes should be credited as well for a relatively non-actorly performance which is nearly as functional. His stooping shuffle and unvarnished innocence are often oddly Bressonian in effect.