Published in Screen Dynamics: Mapping the Borders of Cinema, coedited by Gertrud Koch, Volker Pantenburg, and Simon Rothoehler and published by the Austrian Film Museum in 2012. A year later, this was already out of date in some particulars, but I haven’t attempted to update it. — J.R.

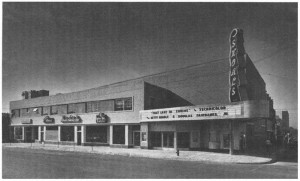

Shoals Theater, Florence, Alabama, 1948

Shoals Theater, Florence, Alabama, 2008

It’s a strange paradox, but about half of my friends and colleagues think that we’re currently approaching the end of cinema as an art form and the end of film criticism as a serious activity, while the other half believe that we’re enjoying some form of exciting resurgence and renaissance in both areas. How can one account for this discrepancy? One clue is that most of the nay-sayers tend to be people around my own age (66) or older whereas most of the optimistic ones are a good deal younger (most of them under 30).

I tend to feel much closer to the younger cinephiles on this issue than I do to the older ones. But I must admit that much of the confusion arises from the fact that the two groups typically don’t mean the same things when they use terms like “cinema,” “film,” “movie,” “film criticism,” and even “available”. The older group is usually referring to what they can see in 35-milliemeter and in movie theaters and what they read or write about in publications on paper that they either subscribe to by mail or purchase in book stores or newsstands. The younger group is mainly speaking about the DVDs that they watch in their homes or at the homes of their friends and the blogs or sites that they access on the Internet. Furthermore, when the older group speaks specifically about films that are “available,” they mean films showing in theaters in their own towns or cities; what the younger group means by “available” is usually (a) available for rental at their local video store or by mail subscription (though American companies such as Netflix), (b) available for purchase through the mail, either nationally or (at least if they have a multiregional DVD player) internationally, and/or (c), among the more hardcore and specialized cinephiles, available via swapping or copying among friends and acquaintances (either locally or internationally).

Perhaps the strangest single aspect of this generational confusion about “cinema” is that we’re all still using the same terms for practices and objects that are radically different from one another. Our terminology is developing at a far slower rate than either our technology or what we call our film culture, producing a time lag that winds up confusing everyone.

***

It’s hard for me to specify too precisely when my first encounter with cinema was, because from circa 1915 to 1960, film exhibition qualified as my family’s business. My paternal grandfather, Louis Rosenbaum, opened his first movie theater, the Princess, in Douglas, Wyoming, around the same time that D.W. Griffith was shooting The Birth of a Nation three states west of there, in southern California. (The Princess’s first program included A Fool There Was, with Theda Bara.) Later the same year, my grandfather built another movie theater called the Princess in North Little Rock, Arkansas, where he moved with his wife and four-year-old son, and four years after that he moved with them still again to Florence, Alabama, where he built his third, largest, and final movie theater to be called the Princess — this one also an opera house presenting an average of twenty-five stage shows a year as well as films. A few of the famous people who appeared there during its first couple of decades (1919-1939) were cowboy stars Gene Autry and Lash LaRue, violinist Mischa Elman, composer W.C. Handy (the composer of “St. Louis Blues,” who had been born in Florence), writer Carl Sandburg, former President William Howard Taft, and jazz musicians Gene Krupa and Fats Waller (who, during Prohibition, demanded and received a quart of vodka from the management before he would agree to appear).

I was born a little after this period, in 1943. By this time, my grandfather had opened at least half a dozen other movie houses in northwestern Alabama and hired his only child, Stanley, to help him manage them. Almost a year before I entered grammar school, the Rosenbaums opened their biggest establishment, the Shoals (see photographs, above) — the fourth largest in the state, with 1350 seats, named after nearby Muscle Shoals, with a sign whose flickering neon was designed to mimic the tumbling spillways at Muscle Shoals’ Wilson Dam on the Tennessee River, one of the largest such dams in the world. So already, by the time the Shoals opened, I had been attending movies at the Princess and perhaps other Rosenbaum theaters for at least a year and a half. I can still remember being frightened a little by the supernatural trappings of That Lady in Ermine, the Shoals’ opening attraction, starring Betty Grable as both Angelina, the ruling countess of an Italian principality in 1861, and her ancestor Francesca, three centuries earlier, who came to life from a painting to help Angelina out when the Hungarian army invaded.

Once I could enter theaters on my own, my consumption of movies went up considerably. In Florence, the Princess, the Shoals, and the Majestic, all three of which could be found within the same three-block radius, generally showed about a dozen films a week, and I usually got to see at least half of these. Then, after the Majestic closed its doors for good in mid-1951, I generally made it to almost everything that played at the two other theaters, some of them occasionally more than once, for the next eight years — until I left for boarding school in Vermont in the fall of 1959.

A little more than a year after that, while I was still off at school, the theaters that were still open were sold — Rosenbaum Theaters having shrunk by then from nine operating theaters to five. My grandfather retired, and my father began teaching American and English literature at Florence State University, known today as the University of North Alabama. And less than a decade after that, in New York, I became a professional film critic — a practice that I then continued for almost eight years in Europe (Paris and London) before I resumed it in the U.S.

***

Only two weeks ago, in March 2009, I returned to Florence to give the keynote address for a conference on world cinema held at the University of North Alabama. This lecture was given for about two dozen people in the balcony of the Shoals Theater — which 29 years earlier had stopped showing movies for good, closed its doors, and then reopened them only sporadically for a few local stage productions, concerts, and similar events, meanwhile repainting the auditorium’s walls and ceiling and rebuilding and expanding the stage. The conference — a private event, closed to the general public, which continued on the university campus the following day — was timed to overlap with the start of an annual film festival, then in its twelfth year. The latter event was named after and founded by George Lindsay, a TV actor and University of North Alabama alumnus, and was open to the general public; it showed films exclusively on projected DVDs, in various nearby shops and cafes. (All the local commercial movie theaters in the area today are located in various shopping malls several miles away and have no connection of any kind with the film festival.)

The night after I gave my keynote address, the Shoals launched the George Lindsay Film Festival with a tribute to two other journeyman actors who are mainly known for their TV work in the 60s and 70s, Rance Howard and Lee Majors, who had both recently been cast by a local woman filmmaker (who was interviewing them onstage at the Shoals) to play in a locally produced feature that’s still in preparation. This time, none of the balcony seats but most of the thousand or so seats downstairs were filled, and the evening began with projected DVD clips from various TV shows and features that the two actors had appeared in, including a few features — such as Howard in Cool Hand Luke (1967) and Majors in Will Penny (1968) — that four decades earlier had shown on the big screen at the Shoals, in 35-millimeter. Only now the screen, a mere fraction as big, was planted directly behind the two actors and hostess on the stage, who were seated in swivel-chairs, and even though the brief excerpts from both of these CinemaScope films were letterboxed (that is, shown in the proper screen ratio), their impact was hardly the same.

I could mention many other changes that have taken place in Florence over the past half-century. Politically speaking, the area was both Democrat and relatively liberal while I was growing up; today it’s so staunchly Republican that I’m told that only about 10% of the local white population voted for Barack Obama. While I was growing up, movies played a central role in the life of the entire community, including every age group — a role that was eventually superseded first by television and then by the Internet, to the point where movies now cater mainly to teenagers and younger kids.

***

Much of what follows is drawn from what I said in my keynote address on my first evening in Florence, in the Shoals balcony. I begin mainly with the topic of writing about film on the Internet and then branch out from there to talk about contemporary filmgoing and film culture more generally.

There’s a part of me that understands perfectly why a minimalist like Jim Jarmusch and a 19th century figure like Raul Ruiz won’t have anything to do with email. “You can’t smell email,” Ruiz once said to me, to explain part of the reason for his distaste. But I find it tougher to feel nostalgic about film criticism before the Internet, because even though you could smell it, the choices of what you could lay your hands on outside a few well-stocked university libraries were fairly limited. Similarly, the choices of what films you could see outside a few cities like New York and Paris before DVDs was pretty narrow, and possibly even more haphazard than what you could read about them.

These two developments shouldn’t be considered in isolation from one another. The growth of film writing on the web — by which I mean stand-alone sites, print-magazine sites, chatgroups, and blogs — has proceeded in tandem with other communal links involving film culture that to my mind are far more important than the decline in the theatrical distribution of art films and independent films, so I’ll be periodically discussing those links here.

When I started out as a cinephile in New York in the early 60s, the English-language magazines that counted the most were the ones that went furthest in gathering together diverse constituencies: Sight and Sound, Film Culture, and Film Quarterly. Even the more local and partisan New York Film Bulletin was translating texts from Cahiers du Cinéma. Of course the film world was much smaller then, and some of the nostalgia for that era undoubtedly focuses on the coziness. By the time film writing on the web started, film culture had spread and splintered into academia and journalism, which often lamentably functioned as mutually indifferent or sometimes even mutually hostile institutions. So the theoretical golden age, I assume, took place before all the institutionalizing.

Significantly, the most enterprising early efforts to disseminate film writing on the web were neither American nor English but Australian — most notably the academic and peer-reviewed Screening the Past, founded by classical and fine arts scholar Ina Bernard in Melbourne in 1997, and the more journalistic Senses of Cinema, founded by filmmaker Bill Mousoulis in the same city in 1999. Both publications are still going strong — having published 23 and 49 issues respectively by early 2009, meanwhile continuing to keep all their previous issues online, although Senses underwent several changes after the departure circa 2002 of Mousoulis and another editor, critic Adrian Martin, the latter of whom went on to cofound the no less ambitious Rouge in 2003.

It’s easy to hypothesize that this Australian concentration came from both a highly developed and interactive local film community and a desire both to be recognized by and to communicate with the wider world of cinephilia.More generally, apart from these examples and the more recent www.movingimagesource.us/article, which appears much more frequently and regularly, there are the sites maintained by film magazines (e.g., Sight and Sound, Film Comment, Cineaste, Cinema Scope), which offer samples rather than exhaustive duplications of their latest issues, and those sites that have replaced former magazines on paper, such as Bright Lights. And finally, there are sites that are extremely useful as summaries of and indexes to the activity occurring on other sites, such as David Hudson’s www.ifc.com/blogs/thedaily, Movie Review Query Engine (www.mrqe.com), and a portal mainly devoted to the film industry, www.moviecitynews.com.

My acquaintance with blogs and chatgroups has started more recently, and been more limited, but a few of each might be mentioned here. Among the more notable critics’ blogs are one devoted to Serge Daney in English (http://sergedaney.blogspot.com) and others in English maintained by David Bordwell (an academic who largely uses his beautifully designed site to update and expand many of his writings on paper), Fred Camper, Steve Erickson, Chris Fujiwara, Glenn Kenny (who calls his own site Some Came Running, after the 1958 Vincente Minnelli feature), and myself. And the main chatgroups I’m familiar with — which differ from the blogs by virtue of the fact that others can and often do contribute to the discussions on them — are an excellent one maintainedby the New York Times critic Dave Kehr (who contributes a weekly DVD column), the auteurist “a film by” maintained by Yahoo, www.theauteurs.com, and a few separate chatgroups located on the elaborate site www.wellesnet.com (“the Orson Welles web resource”). (The latter calls to mind a slew of other director-based sites which are not chatgroups, including especially impressive ones devoted to Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, Jonas Mekas, and Jacques Tati.)

How wide are the readerships of such resources? Klaus Eder, who for many years has been the general secretary of FIPRESCI, the international film critics organization, told me in 2006 that Undercurrent — an online, English-language magazine established that year on their website and edited by Chris Fujiwara, that had then published only three issues (and has only had one subsequent issue since then) — had about 100,000 readers per month. Considering how highly specialized this magazine’s turf is — encompassing such arcane topics as the late film critic Barthélemy Amengual, Alexander Dovzhenko, the acting in Don Siegel’s Madigan, Austrian cinema, sound designer Leslie Schatz, assorted short films, and recent features about Cameron Crowe, Philippe Garrel, Danièle Huillet, Terrence Malick, Park Chan-wook, and Tsai Ming-liang — and considering that 100,000 readers seems to comprise more than those of all film magazines on paper combined, this was a startling piece of information, and one that initially beggared belief. It was also hard to square this figure with one given to me the same year by Gary Tooze regarding a piece of mine called “Ten Overlooked Fantasy Films on DVD (and Two That Should Be!)” on his much more commercial and consumer-oriented web site, DVD Beaver. (In that case, he estimated about 10,000 hits during the first week the article was posted.)

But once Klaus added that the average length of time spent by each reader of Undercurrent was roughly two minutes, I started to realize that my shock was premature, and that my superimposition of two incompatible grids — one devoted to subscribers and readers of paper magazines such as Cahiers du Cinéma, Film Quarterly, and Sight and Sound, the other devoted to web surfers — could only lead to muddled conclusions. And I’m not sure that the comparison with DVD Beaver is very meaningful without the average length of time of each hit in that case, which I don’t know.

Regarding my own web site, which I launched a little less than a year ago, I can be somewhat more precise. According to Google Analytics’ Dashboard, checked most recently on March 2, 2009, this site received 14,467 visits from 8,292 people and 29,007 “pageviews” over the previous month. These visitors used 62 languages and came from 108 countries or territories. (The highest number of visitors in one day was 827 on February 28, shortly after an old article of mine about Basic Instinct was posted.) 8,584 came from the U.S., 1,177 from Canada, 826 from the U.K., and 326 from Australia. Among non-English-speaking countries, I’ll cite only a few figures: 275 from Sweden, 266 from Germany, 255 from Spain, 238 from France, 210 from India, 184 from Japan, 104 from Argentina, 101 each from Finland and Russia, 42 from China, 39 each from Austria, Ireland, and Norway, and one each from Albania, Algeria, Angola, Bermuda, Bolivia, Brunei, Cameroon, the Cayman Islands, Georgia, Guam, Honduras, Kenya, Kuwait, Libya, Malta, Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Nepal, Netherlands Antilles, Oman, Senegal, Trinidad and Tobago, and Vietnam.

Extrapolating from all this, I think that current claims that film criticism is becoming extinct, and counter-claims that it’s entering a new golden age, are equally misguided if they assume that film criticism as an institution functions the same way on paper and in cyberspace, as two versions of the same thing rather than as separate enterprises. Related debates about the distribution of foreign films in the English-speaking world (drastically shrinking in theaters, drastically expanding in the production and distribution of DVDs), or the sophistication of young filmgoers regarding film history (growing if you follow some chatgroups, declining if you follow certain others), or the number of films that get made (even more difficult to determine if videos and films are treated interchangeably) seem equally incoherent due to the disparity of reference points, creating a Tower of Babel in a good many discussions. As suggested above, it’s a central aspect of our alienated relation to language that when someone says, “I just saw a film,” we don’t know whether this person saw something on a large screen with hundreds of other people or alone on a laptop — or whether what he or she saw was on film, video, or DVD, regardless of where and how it was seen.

In short, we’re living in a transitional period where enormous paradigmatic shifts should be engendering new concepts, new terms, and new kinds of analysis, evaluation, and measurement, not to mention new kinds of political and social formations, as well as new forms of etiquette. But in most cases they aren’t doing any of those things. We’re stuck with vocabularies and patterns of thinking that are still tied to the ways we were watching movies half a century ago. And the way critics as well as films become canonized continues to be a rather haphazard process. A major figure such as the late English film critic Raymond Durgnat is almost completely unknown today, even in the U.K., because most of his major books have long been out of print and very little of his work has ever become available online. And it’s no less anomalous that there’s a web site devoted to Serge Daney in English but not one devoted to his writings in French.

Indeed, one could argue that film overall has fared better than film criticism. When I taught film history at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the mid-80s, I felt seriously hampered by the fact that I couldn’t rent copies of anything by one of my favorite filmmakers, Louis Feuillade, apart from one section of his Fantômas (1913-1914), and his work was so poorly known by my colleagues that none of my predecessors who taught film history had ever included him in the syllabus. Today, all of Fantômas and two of Feuillade’s subsequent serials, Les vampires (1915) and Judex (1916), are available on DVD in excellent editions, complete with English titles. And practically all of the major works of another favorite filmmaker, Carl Dreyer, are currently available on DVDs with superb sound and image — something that was almost never the case when I was trying to discover his work during previous decades.

Yet if I wanted to support the argument that we’re approaching the end of cinema as an art form, I could probably point towards certain depressing aspects of the George Lindsay Film Festival — such as the total absence of any films shown there (as opposed to DVDs) and the terrible quality of much of what was shown (judging by the prizewinners that I saw on the festival’s final day). I could also point towards the anti-art biases of academic film study in the U.S — not to mention the fragmented and alienated notion of film culture reflected and even encouraged by the fact that the conference I spoke at in Florence was closed to the general public.

In fact, there are times when I think pessimistically that we’re kept further apart than we ever were before — subdivided into separate target audiences, markets, and DVD zones, territorialized into separate classes and cultures — in spite of our common experiences. This suggests that the technology that supposedly links us all together via phones and computers are actually keeping us all further apart, and not only from each other but also, in a sense, from ourselves. In other words, our sense of our own identities, including especially our social identities, becomes fragmented and compartmentalized, and even the operations of Internet chatgroups might be said to provide a major illustration of this trend.

Perhaps this paradox about so-called “communications” impeding communication has always been the case. But I think the example of mobile phones illustrates such a cultural difference more vividly than many of the others. Personally, I despise mobile phones when I encounter other people using them on the buses and streets of Chicago, because I experience them as a rejection of myself as a fellow passenger or pedestrian. One used to assume, whenever one saw a person walking down the street speaking loudly to no one in particular, that this person was insane. Today one commonly assumes that this same person is a sane individual speaking to someone else on a phone, but it might also be possible to assume that the implied rejection of one’s immediate surroundings suggests another kind of insanity, based no less on an antisocial form of behavior

Yet I have to acknowledge that for a young person who lives with her or his family and feels in desperate need of some kind of privacy, a mobile phone may also represent a kind of liberation. Indeed, according to front-page story in the New York Times a few years ago (April 25, 2005), “About 27% of China’s 1.3 billion people own a cellphone, a rate that is far higher in big cities, particularly among the young. Indeed, for upwardly mobile young urbanites, cellphones and the Internet are the primary means of communication.” And the fact that many films today can be watched on cellphones and discussed on the Internet only underlines the transformation that our film culture is currently undergoing.

***

It might help our discussion if we start redefining what we mean by community in relation to geography, which is central to all these paradigmatic shifts. It becomes relevant, for example, that Chris Fujiwara edits Undercurrent from Tokyo as well as from Boston, and that the editor of Film Quarterly, published by the University of California Press, works out of London — and perhaps even that this sentence was initially written while I was on a plane between Chicago and Vancouver — especially if we persist in regarding the discourse of both magazines as a discourse being aimed at a specific geographically-based constituency seen in relation to a particular nation-state, town or city, university or other institution. Speaking as someone who currently feels that he lives on the Internet more than he lives in Chicago, I consider this distinction vital to the ways that I function as a writer. Maybe it’s also relevant that Rouge, the most ambitious of the international online film magazines (translating some of its texts into English from Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, and Spanish sources), originates from Australia — or at least from three Australian editors, who may at any given time be in France, Greece, or elsewhere while doing part of their editorial work. But if it is relevant, this is largely because Australia is itself multicultural, also yielding a multicultural, state-run TV channel, SBS, that similarly has few counterparts.

It’s my own conviction that the nation-state itself is fast becoming an outdated and dysfunctional concept, apart from the special interests of politicians and corporations and their own highly functional designation of countries as markets. The choices of ordinary filmgoers are said to be steadily shrinking at the same time that most of the known riches of world cinema are becoming internationally available for the first time on DVD. So if I wanted to counter the argument that we’re approaching the end of cinema as an art form, there’s plenty of hopeful evidence that I could point towards as well.

Thanks to the site of the Canadian film magazine Cinema Scope, where I write a regular column called “Global Discoveries on DVD” that usually appears online (at www.cinema-scope.com), I received one of the most exciting glimpses of the utopian possibilities inherent in film writing on the web. For some time, I have been fantasizing that ciné-clubs, a major spur to French cinephilia over most of the past century, could be making a comeback, this time in global terms, thanks to DVDs. These ciné-clubs could be situated almost anywhere, in houses and apartments as well as in storefronts, and a model configuration might be touring “retrospectives” on DVD in which the DVDs could be sold at the screenings (perhaps along with relevant books and/or pamphlets), in much the same way that CDs are now often sold by music groups in clubs between their sets. And if enough circuits for these retrospectives could become established in this fashion, this could ultimately finance the production of these packages. In some ways this dream has already been realized in the U.S. by www.moveon.org and the way it has arranged private showings of such Robert Greenwald documentaries as Uncovered, Out-Foxed, Wal-Mart, and Iraq for Sale, but it doesn’t appear to have caught on with other kinds of films. Yet if I started to dream about another direction that the George Lindsay Film Festival could take — one which concentrated on great films of the past or near-past rather than mediocre films of the present (even if they’re all still screened on DVD), and one which bypassed the dubious standards of the multiplexes for more challenging and interesting fare — there are certainly some precedents I could cite.

I could start by mentioning some of my younger cinephile friends, including some who are still in their 20s and already know more about film history, thanks to multiregional DVD players, than I possibly could have known in my own early 30s, when I was educating myself about such matters in New York, Paris, and London. Some of these friends, moreover, live in relatively remote places, such as rural England (in two cases) or a small town in Spain — implying that the cultural dominance previously enjoyed by critics and viewers living in the major capitals of Europe and the U.S is no longer the same thing that it used to be. Today one can live just about anywhere — even Florence, Alabama — and still have access to a surprising number of the major works of film history, at least if one knows where and how to go looking for them.

While attending the Mar del Plata film festival in Argentina a few years ago, I met a schoolteacher based in Cordoba who had established a few ciné-clubs in separate small towns that he visited on a regular basis, and the films he showed included some of the more specialized and esoteric films I had written about, including Forough Farrokzhad’s The House is Black (1962), an Iranian short about a leper colony by one of that country’s greatest poets, and Kira Muratova’s Chekhov’s Motifs (2002). He told me the combined audiences of such screenings for each film was somewhere between 700 and 800 people. Considering how unlikely it would be to fill single auditoriums of that size in most major cities of the world for such films, I realized that the shifting paradigms of today might also transform what we normally regard as a minority taste. Once the paradigm of a single geographical base changes, all sorts of things can be transformed. Maybe Muratova’s craziest feature is too difficult for most New Yorkers and Parisians, but once it can be acquired globally on DVD with the right subtitles, anything becomes possible — including a sizable group of viewers in Cordoba.