Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/ collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

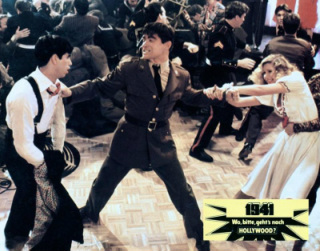

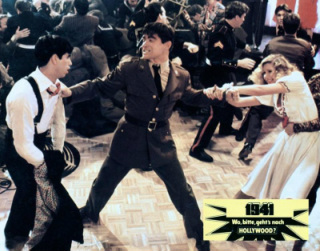

1941 (1979)

One of Steven Spielberg’s most underrated films is

not only a virtuoso piece of filmmaking but a flagrant

piece of mean-spiritedness and teenage irreverence

that underlines aspects of his work that his more popular

and commercially successful works tend to either

disguise or rationalize. Both of these qualities

are partially the contributions of cowriter Robert

Zemeckis –- who exhibits these traits more independently

on such later features as Used Cars (1980)

and Forrest Gump (1994). But there’s also a strain

that one might associate with the more progressive

and Tashlinesque reflexes of a Joe Dante, helping to

explain why John Wayne not only refused indignantly

to play in this comedy but also tried to persuade

Spielberg that making such a movie was tantamount

to spitting on the American flag. In Spielberg’s

hands, much of the comedy here seems to derive

from a desire to see large sets destroyed as if they

were Tinker toy constructions, complete with tuttifrutti

mixtures of splattered paint, and without the

messy inconvenience of either deaths or morals. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 2000). — J.R.

I find critics’ near unanimity about hits and favorites a bit of a bore, even when I agree with some of their choices. Disputes are far more interesting, because they make artistic and political differences clearer and more meaningful. Perhaps because I’m drawn to cinema that can theoretically change the world — and me — I can’t see much purpose in commemorating movies whose prime aim seems to be to make me forget the world outside the theater. The remake of The Thomas Crown Affair and an evening of channel surfing, no matter how enjoyable either might be, are of roughly equal irrelevance.

Nineteen ninety-nine was a pivotal year in movies, clarifying where a lot of people stood and who they were. This kind of definition was encouraged by the existential stocktaking that came with the end of the millennium — the compiling of more best-film lists than usual (of the 90s, of the century) and more generalized meditating on the state of the art and the medium. (After finishing my own best-of-the-90s list for the last issue of the year, I discovered that all but one of the movies had an interesting trait in common: they hadn’t been reviewed in the New Yorker. Read more

This article was originally published in Stop Smiling no. 27 (“Ode to the Midwest”) in 2006. It’s also reprinted in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

Kim Novak as Midwestern Independent

It’s possible that the star we know as Kim Novak was partially the invention of Columbia Pictures —- conceived, as the Canadian critic Richard Lippe puts it, both as a rival/spinoff of Marilyn Monroe and as a replacement for the reigning but at that point aging Rita Hayworth. At least this was the favored cover story of Columbia studio head Harry Cohn, whom Time magazine famously quoted in 1957 as saying, “If you wanna bring me your wife and your aunt, we’ll do the same for them.” It was also the treasured conceit of the American press at the time, which was all too eager to heap scorn on Novak for presuming to act — just as they were already gleefully deriding Monroe for presuming to think. But Monroe, as we know today, was considerably smarter than most or all of the columnists who wrote about her. And Kim Novak — a major star if not a major actress — had something to offer that was a far cry from updated Hayworth or imitation Monroe (even if the latter was precisely what Columbia attempted to do with her in one of her first screen appearances, in the 1954 Judy Holliday vehicle Phffft! Read more

Published in Screen Dynamics: Mapping the Borders of Cinema, coedited by Gertrud Koch, Volker Pantenburg, and Simon Rothoehler and published by the Austrian Film Museum in 2012. A year later, this was already out of date in some particulars, but I haven’t attempted to update it. — J.R.

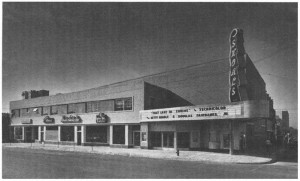

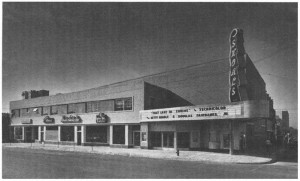

Shoals Theater, Florence, Alabama, 1948

Shoals Theater, Florence, Alabama, 2008

It’s a strange paradox, but about half of my friends and colleagues think that we’re currently approaching the end of cinema as an art form and the end of film criticism as a serious activity, while the other half believe that we’re enjoying some form of exciting resurgence and renaissance in both areas. How can one account for this discrepancy? One clue is that most of the nay-sayers tend to be people around my own age (66) or older whereas most of the optimistic ones are a good deal younger (most of them under 30).

I tend to feel much closer to the younger cinephiles on this issue than I do to the older ones. But I must admit that much of the confusion arises from the fact that the two groups typically don’t mean the same things when they use terms like “cinema,” “film,” “movie,” “film criticism,” and even “available”. Read more