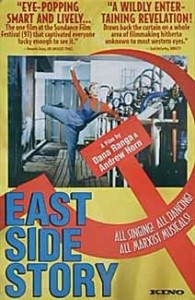

East Side Story, a recent documentary about communist musicals, assumes that communist-bloc directors were just itching to make Hollywood extravaganzas and invariably wound up looking strained, square, and ill equipped. But Red Psalm (1971), Miklos Jancso’s dazzling, open-air revolutionary pageant, is a highly sensual communist musical that employs occasional nudity as lyrically as the singing, dancing, and nature; within its own idioms it swings as well as wails. Set near the end of the 19th century, when a group of peasants have demanded basic rights from a landowner and soldiers arrive on horseback, it’s composed of less than 30 shots, each one an intricate choreography of panning camera, landscape, and clustered bodies. Jancso’s awesome fusion of form with content and politics with poetry equals the exciting innovations of the French New Wave in the 60s and early 70s. The music, ranging from revolutionary folk songs to {Charlie Is My Darlin’,} will keep playing in your head for days, and the colors are ravishing. The picture won Jancso a best director prize at Cannes, and it may well be the greatest Hungarian film of the 60s and 70s, summing up an entire strain in his work that lamentably has been forgotten here. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1998). — J.R.

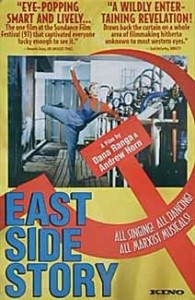

The words “communist musical” may call to mind tractors and factories — both of which are certainly in evidence here — but this fascinating and enjoyable 1996 documentary by Romanian-born filmmaker Dana Ranga and American-born independent Andrew Horn presents the singular genre as a conflict between capitalist glitz and socialist poetry, revealing both the Marxists’ tragicomic attempts to beat the West at its own game and the homegrown folksiness of their efforts. Reportedly only 40-odd musical features were produced in the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, and Romania prior to the collapse of communism, and roughly half of them are excerpted here. Ranga and Horn interview writers, directors, stars, and ordinary viewers of communist musicals, as well as one prestigious film historian (Maya Turorskaya, best known here for her book on Andrei Tarkovsky). The selection of clips isn’t everything it might have been — I regret the absence of any examples by Alexander Medvedkin, some of which are glimpsed in Chris Marker’s The Last Bolshevik, and eastern European critics have cited other omissions. But Ranga and Horn’s insights into communist film production and their story of how the communist musical triumphed or withered in its various settings offer plenty of food for thought. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1998). — J.R.

A middle-aged man who’s contemplating suicide drives around the hilly, dusty outskirts of Tehran trying to find someone who will bury him if he succeeds and retrieve him if he fails. This minimalist yet powerful and life-enhancing 1997 feature by Abbas Kiarostami (Where Is the Friend’s House?, Life and Nothing More, Through the Olive Trees) never explains why the man wants to end his life, yet every moment in his daylong odyssey carries a great deal of poignancy and philosophical weight. Kiarostami, one of the great filmmakers of our time, is a master at filming landscapes and constructing parablelike narratives whose missing pieces solicit the viewer’s active imagination. Taste of Cherry actually says a great deal about what it was like to be alive in the 1990s, and despite its somber theme, this masterpiece has a startling epilogue that radiates with wonder and euphoria. In Farsi with subtitles. 99 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 25, 1998). — J.R.\

This unusually charming and touching Ismail Merchant-James Ivory film feels closer to memoir than fiction; it’s drawn from an autobiographical novel by Kaylie Jones (daughter of novelist James Jones), but Ivory, working with his usual screenwriting collaborator, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, reportedly fleshed out the story with some of his own experiences. In “Billy,” the first of the film’s three sections, an expatriate novelist in Paris (Kris Kristofferson) and his wife (Barbara Hershey) adopt a six-year-old French boy who’s initially resented by the couple’s natural daughter. “Francis,” set a few years later, recounts the daughter’s friendship with an eccentric American schoolmate (Anthony Roth Costanzo), and Jane Birkin has a field day as his doting single mother. Yet these last two characters, as well as the family’s maid (Dominique Blanc) and her boyfriend (Isaac de Bankole), disappear in “Daddy,” which follows the family’s return to the States once the siblings are teenagers and the father’s health is deteriorating. The three parts add up to a rather lumpy narrative, and the characters are perceived through a kind of affectionate recollection that tends to idealize them, but they’re so beautifully realized that they linger like cherished friends. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 5, 1999). — J.R.

Raul Ruiz’s first mainstream release, which is getting its Chicago premiere at an art house rather than a multiplex, may not be one of his best — given his hundred or so shorts and features, there’s a lot of competition, and this is one of the rare Ruiz movies scripted by someone else. But it certainly provides some provocative and enjoyable jolts. Anne Parillaud plays a professional assassin in Seattle who dreams she’s a vulnerable newlywed honeymooning in the Caribbean and recovering from a rape; she also plays a vulnerable bride who dreams she’s an assassin. William Baldwin plays the significant other of both women, bearing the same name, and the contrapuntal play between Parillaud the victimizer and Parillaud the victim is pushed to dizzying extremes. Beautifully shot by Robby Muller, with periodic allusions in the score (by Ruiz regular Jorge Arriagada) to Bernard Herrmann’s work for Hitchcock, this head-scratching thriller should keep you entertained throughout, at least if you’re feeling adventurous. Ruiz didn’t even have final cut, but he clearly enjoyed himself making this film. Duane Poole wrote the distinctly Ruizian script, featuring twists at every turn, and the costars include Graham Greene and Bulle Ogier. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1999). — J.R.

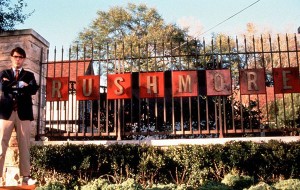

Wes Anderson’s second feature (1998) has some of the charm and youthful comic energy of its predecessor (Bottle Rocket), also coscripted by Owen Wilson, but it also represents a quantum leap. Jason Schwartzman plays an ambitious working-class tenth grader who’s flunking out of a private school — the Rushmore of the title — because he’s too engrossed in extracurricular activities. To make matters worse, he develops a crush on a young widow (Olivia Williams) who’s a grammar-school teacher there. His two best friends are a schoolmate who’s much younger and a disaffected millionaire alumnus (Bill Murray) who’s much older, and part of the lift of this movie is that it creates a utopian democracy among different age groups. Things come to a crisis when the millionaire becomes the hero’s romantic rival. Stylistically fresh and full of sweetness that never cloys, this is contemporary Hollywood filmmaking at its near best. R, 93 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1998). — J.R.

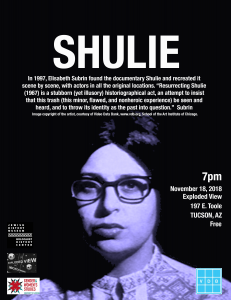

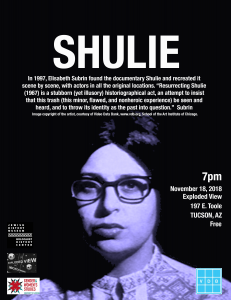

For the most part, this is a precise, shot-by-shot video “remake” of a little-known half-hour documentary film made in Chicago in 1967. The original film, made by Jerry Blumenthal, Sheppard Ferguson, James Leahy, and Alan Rettig, was a portrait of 22-year-old Shulamith Firestone as she was earning a BFA in painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute, working for the postal service, and taking photographs (three years later she would publish The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution). The “remake” was made by Elisabeth Subrin (Swallow), a former grad student at the School of the Art Institute who worked with actors and detailed reproductions of Firestone’s paintings and drawings. This fascinating attempt at duplication ultimately has more to say about the 90s than the 60s: though it has some impact of its own as a document about prefeminist awakening, it?s more valuable as a commentary on what separates the past from the present. Kim Soss gives a good performance as Firestone, but her style of speaking is noticeably more guarded and unemotional, telling us a great deal about differences in everyday speech and body language 30 years apart. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1998). — J.R.

As in House of Games, David Mamet tries his hand at a Hitchcockian thriller, this time exploring the chase film rather than obsessive behavior. The effect is altogether lighter — a souffle that periodically threatens to float away. Campbell Scott plays the inventor of something called the Process (Mamet’s MacGuffin), a top-secret formula his company expects to clean up on. About the time that he’s befriended by a mysterious businessman (Steve Martin), he starts to worry that he might be cheated out of a share of the profits. The conspiracies come fast and thick, but because Mamet’s interest — male gamesmanship and competition — is pretty distant from Hitchcock’s usual turf, the spectator winds up feeling less invested in the plot and characters. But this 1998 feature is fun if you’re looking mainly for light entertainment. With Ben Gazzara, Rebecca Pidgeon, and Ricky Jay. PG, 112 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the January 30, 1998 Chicago Reader. Since I barely remember Kundun today, I’m pretty sure I must have overrated it, at least in relation to The Apostle (which I remember far better today, even in its truncated version). –J.R.

The Apostle

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by

Robert Duvall

With Duvall, Farrah Fawcett, Miranda Richardson, Todd Allen, John Beasley, June Carter Cash, Billy Joe Shaver, Walter Goggins, Rick Dial, and Billy Bob Thornton.

Kundun

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Melissa Mathison

With Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong, Gyurme Tethong, Tencho Gyalpo, Tsewang Migyur Khangsar, Geshi Yeshi Gyatso, and Robert Lin.

For all their obvious differences, both Kundun and The Apostle are spiritual but nonreligious movies about religious leaders, suffused with a perpetual sense of mystery and driven by an abiding curiosity that provokes our own curiosity as well. As a commercial property, each film amounts to an act of defiance, judging by their critical reception so far. Many mainstream critics have stepped out of Kundun asking, “What could Scorsese have been thinking of?,” and some have come out of The Apostle complaining that it’s basically an ego trip for its writer-director-star.

Both reactions perversely miss the point, telling us more about stereotypical commercial expectations in general than about either project in particular. Read more

This is an expanded version of an article published originally (on October 8, 1993) in the Chicago Reader; the Australian DVD label Madman commissioned this longer piece in the summer of 2009. — J.R.

Let’s start with a dream scenario, a movie that might have been. What if Luis Buñuel made a picture with an American producer, American screenwriter, and American actors during the height of the civil rights movement and set it in the rural south? What if the main character were a jazz musician from the north fleeing from a southern lynching, falsely accused of raping a woman? And, to make a still headier brew, what if Buñuel decided to work in the theme of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a recent best-seller — the deflowering of a young girl by a middle-aged man?

As a piece of exploitation, this hypothetical project fairly sizzles; yet in the hands of a poetic, corrosive, highly moral filmmaker like Buñuel, it might conceivably transcend this category. Allowing for the strangeness that naturally arise from a foreign director taking on such volatile American materials — indeed, a strangeness that might enhance the freshness of his treatment -—one could well anticipate the beauty and excitement such an encounter might produce. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 8, 1996). — J.R.

The White Balloon

Directed by Jafar Panahi

Written by Abbas Kiarostami, Panahi, and Parviz Shahbazi

With Aida Mohammadkhani, Mohsen Kalifi, Fereshteh Sadr Orfani, Anna Bourkowska, Aliasghar Samadi, Mohammad Shahani, and Mohammad Bahktiari.

In Iran the first day of spring is New Year’s Day, the celebration of which starts at a different time of day every year, and among the objects used in the celebration is a goldfish, which symbolizes life. The plot of Jafar Panahi’s extraordinary first feature, The White Balloon (opening this week at the Music Box), involves the adventures of Razieh (Aida Mohammadkhani), a seven-year-old girl who has her heart set on buying a new goldfish for the celebration, insisting that the ones her family already has are “too skinny.”

Only 85 minutes long, the film unfolds in real time and almost exclusively in exteriors along a few blocks of Tehran the morning of the New Year. The film opens in a market, where Razieh’s mother (Fereshteh Sadr Orfani) is shopping; she collects Razieh, who’s carrying a blue balloon, and they walk home together. Nearly all of the film’s other major characters — and even a couple of minor ones — are fleetingly glimpsed during this prelude, though we don’t recognize any of them yet. Read more

From the October 6, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Seven

*** (A must-see)

Directed by David Fincher

Written by Andrew Kevin Walker

With Morgan Freeman, Brad Pitt, Gwyneth Paltrow, Richard Roundtree, R. Lee Ermey, John McGinley, Julie Araskog, Mark Boone Junior, and Kevin Spacey.

Since when have designer vomit, mannerist rot, and other chic signifiers of gloom, doom, and decline become such comforting mainstays of movies? I’m thinking not only about Hollywood but about Western cinema generally. What brings on all the driving, dirty rain in Satantango (Bela Tarr’s seven-hour Hungarian black comedy, which showed at last year’s Chicago International Film Festival) as well as in Seven, a stylish and affecting (albeit gory) metaphysical serial-killer movie? The facile solution would be to trace the gloom back to Blade Runner, film noir, maybe even to Prague school surrealism, though this would omit the Calvinist/expressionist vision of urban filth and the post-Vietnam psychopathology of Taxi Driver. In point of fact, it’s much more important to figure out the reasons for the strange allure of this grim sensibility than to worry pedantically about where it came from.

I’d ascribe at least part of this taste to the current inability to believe in or try to effect political change — a form of paralysis that in America is related to an incapacity to accept that we’re no longer number one. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 14, 2011). — J.R.

It’s a fairly safe bet that “List-o-mania,” first published in June 25, 1998, was the most popular piece I published in the Reader during my 20 years there as film reviewer, roughly halfway through my stint there. I suspect its appeal had a lot to do with the growing popularity of movie lists ever since the video market started expanding the choices of most viewers.

Like a commercially successful Hollywood feature, “List-o-mania” had its share of sequels and spinoffs. Retitled “The AFI’s Contribution to Movie Hell,” it became a chapter in my most popular book, Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000), a rant that received over a hundred reviews despite the fact that its small Chicago publisher (a cappella books, a division of Chicago Review Press) couldn’t afford much advertising, aside from freebies in the Reader, and I never even met my publicist there.

In the book, I added in a footnote a list of 25 titles in the AFI’s list that I probably would have included if I’d started my own list from scratch. Then, as an appendix to my 2004 collection Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (Johns Hopkins University Press), I compiled a chronological list of my 1000 favorite films, with asterisks next to my 100 crème de la crème, this time including shorts as well as features and non-American as well as American items—a list to which I added 60 more titles in my Afterword to the 2008 paperback. Read more

Based on feedback, I would guess that this article, which first appeared on June 25, 1998, is the most popular piece I ever published in the Chicago Reader. Although it’s been featured as a separate item for several years on their site, I noticed that, thanks to some of their recent user-unfriendly retoolings of that site — which makes it much harder to access anything and everything, including this article — my own list of my 100 favorite films at the end of this piece and the AFI’s list of the supposedly greatest 100 films somehow got scrambled together. [Update, 7/25/09: Checking back a day later, this now appears unscrambled.] This is mainly why I’ve decided to reprint the original piece here in Notes, with only a few minor modifications. I revised and expanded this piece still further in my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, where it forms the sixth chapter. (I’m sorry that the English edition of this, which has a much better jacket, has become more scarce.) One of the main additions, on page 93, is a list of the 25 titles on the AFI list that I probably would have included on my own if I hadn’t wanted to create an all-new list for polemical purposes; six of these titles are illustrated at the tail-end of this piece. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1975. — J.R.

Romantic Englishwoman, The

Great Britain/France, 1975 Director: Joseph Losey

Elizabeth Fielding arrives in Baden Baden on holiday; on the

same train is Thomas Hursa, carrying a supply of drugs, which he

hides on the roof of the luxury hotel where Elizabeth is staying.

Her husband Lewis, a successful novelist now at work on a

screeinplay about a discontented woman who leaves her

husband, phones her at midnight. While Elizabeth converses

with Thomas in a lift, Lewis imagines her making love with

a man in a similar situation (an image which he uses in his

screenplay); he rings her again at 12:30 and she answers

belatedly, saying that she will be home in Weybridge the

next day. Thomas’ drug supply is destroyed in the rain

and he flees when he discovers that Swan, a drug contact, is

looking for him. When Elizabeth returns at night, she and Lewis

start to make love on their front lawn, but are interrupted by a

neighbor. After expressing his suspicion that his wife was

unfaithful in Baden Baden, Lewis receives a letter from Thomas

describing himself as a poet and admirer of Lewis’ work and

mentioning that he met Elizabeth in Baden Baden. Read more