From Video Movies (August 1984). — J.R.

Zabriskie Point

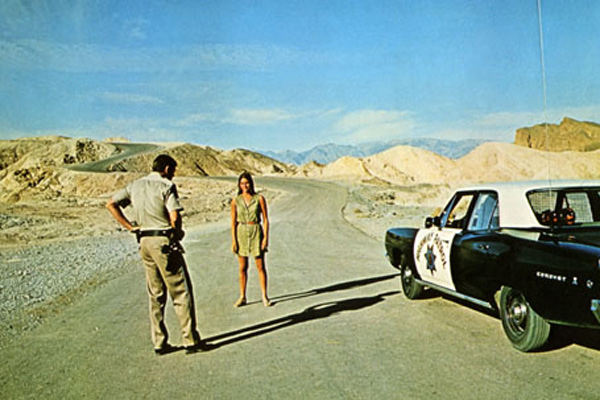

(1969), C, Director: Michelangelo Antonioni. With Mark Frechette, Daria Halprin, Rod Taylor, and Kathleen Cleaver. 111 min. R. MGM/UA, $59.95.

In the 1960s, he could do no wrong, especially after his hit, Blow-up. In the 1980s, Michelangelo Antonioni emerges as a shamefully neglected figure — only one of his last four films (The Passenger) has been released in this country. And Zabriskie Point, the film that virtually destroyed his American reputation, offers ample proof of both the Italian director’s brilliance and his neglect of filmmaking particulars that Americans seemingly will not stand for. To understand Antonioni’s art, we must acknowledge that he is not a storyteller but a composer/choreographer of sounds and images.

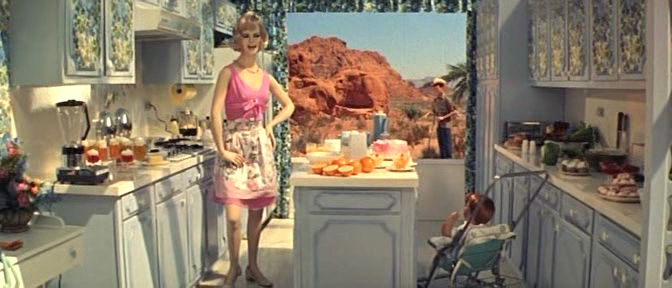

As either a plausible romance about disaffected youth or as a documentary rendering of 1969 America, Zabriskie Point is often ludicrous. But if one keeps in mind that Antonioni thinks through his camera more than through his scripts — and that realism is far from his intention — one can see this film as an astonishingly beautiful achievement. As the director noted at the time, “The story is certainly a simple one. Nonetheless, the content is actually very complex. It is not so much a question of reading between the lines as of reading between the images.” Approached as an allegorical fantasy or as science fiction about the present, the film becomes a poetic meditation about a dream America in a state of crisis. Even with its lavish Panavision frames cropped and shrunk by the video format, it’s better cinema on a shot-by-shot basis than most of the certified hits of 1969 — or 1984.

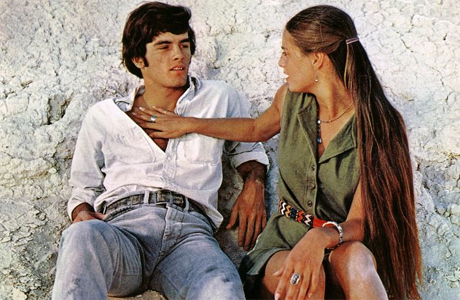

Still, certain obstacles must be acknowledged. The two young lead actors — Mark Frechette (as a hothead and not very bright radical) and Dara Halprin (as a life-enhancing flower child) — were both nonprofessionals, and it shows at every turn. Most of their dialogue is witless, and the plot is a tissue of contrived implausibilities. One can’t claim that these problems are completely transcended by Antonioni’s genius, but it would be equally wrong to assume that they prevent this genius from manifesting itself. Most of the major sequences make scant use of the dialogue or acting, and the plot mainly functions as a pretext for creating these sequences. Moods, landscapes, and a continual oscillation between documentary and abstraction are the central tools at Antonioni’s disposal, and the characters drift through the “dialogue of ambiance” like tour guides from the physical world.

Consider the opening scene, which uses Pink Floyd music over glimpses of student radicals. The meeting is presided over by real-life radical Kathleen Cleaver. As the camera restlessly darts and pans across the room, searching out speakers and listeners in a debate about coping with the police, the rapid shifts of focus and emphasis increase the chaotic effect, so that an abstract shape suddenly turns into upraised arm and an angry verbal retort competes with a visual distraction. Here and elsewhere, Antonioni’s stance may be that of a goggle-eyed tourist, but the quasi-surreal mood he sketches is indelible.

Working wonders with L.A. billboards, high-tech architecture, Death Valley, and other arid settings, Antonioni creates a portrait of a volatile America that he (as a foreigner) and the hippies (as outsiders) see more clearly than others. Starting out from a stolen airplane (Mark’s) and a borrowed Buick (Daria’s), he pivots his eerie romantic plot towards matching dreams of universal love (a lyrical group grope at Zabriskie Point) and mass destruction (an apocalyptic explosion-ballet), imagined in turn by the heroine in spectacular visions.

— JONATHAN ROSENBAUM