From the April 1985 Video Times. — J.R.

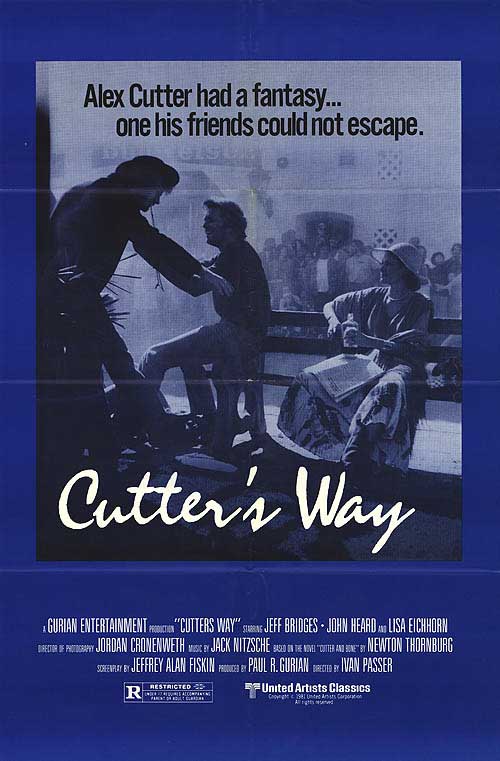

Cutter’s Way

(1981), C, Director: Ivan Passer. With Jeff Bridges, John Heard, Lisa Eichhorn, and Ann Dusenberry. 105 min. R, MGM/UA, $69.95.

A powerful, erotic thriller with remarkable performances from all three of its leads (Jeff Bridges, John Heard, and Lisa Eichhorn), Cutter’s Way never made the impact it should have when it was released. Originally titled Cutter and Bone, after the novel by Newton Thornberg on which it is based, it quickly became a studio write-off in the immediate wake of Heaven’s Gate. Not even a brace of rave reviews and a couple of film festival prizes could save it. Rereleased a few months later as Cutter’s Way, the film went on to acquire an enthusiastic cult that continues to appreciate its sensitive, offbeat mood and its indelible portrait of disaffected America.

The film is tightly scripted by Jeffrey Alan Fiskin and directed by the Czech expatriate Ivan Passer, best known for his bittersweet Czech feature Intimate Lighting, as well as such American features as Born to Win, Law and Disorder, and Silver Bears. Cutter’s Way is an in-depth portrait of the complex relations between three disaffected people. The fact that all three are in some way losers is clearly what endears them to Passer, as well as to us. They wear their marginality like crowns.

On his way back from a hotel assignation with a wealthy married woman (Nina Van Pallandt in a witty cameo), yacht salesman Richard Bone (Jeff Bridges) glimpses a man in the shadows depositing the corpse of a teenage girl in an alley trashcan. The next day, after a police grilling, Bone is watching a parade with his embittered friend Alex Cutter (John Heard), a crippled Vietnam veteran, and Cutter’s alcoholic wife Mo (Lisa Eichhorn). Suddenly, he sees a man in the procession who looks like the man he saw in the alley. This man turns out to be oil tycoon J.J. Cord (Stephen Elliott). Bone is reluctant to get involved, but Cutter insists on mounting an elaborate blackmail scheme against Cord. To complicate matters, the dead girl’s sister (Ann Dusenberry) becomes involved in the scheme, and a mutual attraction develops between Bone and Mo, encouraged by Cutter.

Although the movie has more than its share of suspense, the focus is on character and atmosphere, and as the multiple ambiguities accumulate, the viewer’s involvement undergoes many sea changes. Missing an arm and a leg from his stint in Vietnam, Cutter moves about in a perpetual rage and, despite the alienating aspects of his behavior, we come to care about him deeply, just as our sense of Bone as a simpleminded jock gradually shifts. Shot on location in Santa Barbara, the light and texture of Cutter’s Way has a luminous quality. Whenever two or more of the central characters are on screen at once, one has a sense that almost anything could happen. The legacy of the sixties seems to hover behind Passer’s doomed threesome like a half-remembered dream, and the haunting musical theme by Jack Nitzsche, performed on a glass harmonica and a zither, slides over the action like an eerie hallucination.

A passionate story about friendship, love, and commitment among three powerless people caught in a maelstrom, Passer’s masterpiece plays like a forties film noir transplanted to a wholly contemporary setting. the darkness of the theme is all the more gripping because it belongs to the world we live in today.

— JONATHAN ROSENBAUM