This commissioned essay was for a touring retrospective catalogue, The American New Wave, 1958-1967, published by the Walker Art Center and Media Center/Buffalo in 1982 (and slightly tweaked just now, in June 2010). It’s dated by my erroneous assumption, shared by most critics during this period, that the dialogue of Shadows was improvised, corrected years later by the research of Ray Carney — although I still stand fully behind my opening paragraph. I was also mistaken in my assumption that Charles Mingus was entirely responsible for the film’s score, especially in the second version. (Ross Lipman has written brilliantly and in detail on this subject.)

My writing of this article was both interrupted and ultimately informed by the shock of the suicide of my older brother David. Regarding the details about lapsed Catholicism apropos of The Savage Eye, I can still recall a phone conversation I had at the time with the late Veronica Geng, a former colleague at Soho News (and lapsed Catholic) and a writer and editor at The New Yorker whom I plumbed for information and advice. Perhaps I went a little overboard in my expressions of scorn for the purple prose in The Savage Eye’s commentary; today I find it rather fascinating for its kinship with Beat writing from the same period, for better and for worse. — J.R.

“I don’t think that anything related to Shadows was documentary,” John Cassavetes remarked in an interview published in Films and Filming (February 1961). Yet it seems impossible to discuss the film’s meaning and impact without some reference to the documentary tradition. Just as The Savage Eye situates its own fictional and dramatic narrative within and against a specific documentary sense of place — a Los Angeles perceived through the lenses of Jack Couffer, Helen Levitt, Haskell Wexler (featured photographers), Sy Wexler and Joel Coleman (contributing photographers) — Shadows depends no less crucially on a Manhattan (mainly midtown) perceived by the touristic setups of cameraman Erich Kollmar and his assistant Al Ruban. Significantly, the natural locations and background milieu in both films structure the dramatic shape of many scenes, as if they themselves were producing the narratives.

At the beginning of Shadows, for instance, the three central characters — a young and alienated mulatto hipster (Ben Carruthers), his black older brother who sings in nightclubs (Hugh Hurd), and their 20-year-old, light-skinned flirtatious sister (Lelia Goldoni) — are introduced in separate improvised scenes, and each of these is framed by a specific location and milieu that the camera presents as a documentary subject. The extraordinary ambiance of the actors’ sensitivities is conveyed at once throughout this beginning, which glitters with sudden observations that register like personal discoveries.

Behind the credits, Ben is seen at a crowded, noisy party where loud rock music is playing, completely isolated from the surrounding activity — working his way around the room’s edges with arms upraised, lurking in one corner like James Dean in a trapped animal pose, essentially trying to remain alone in the midst of a mob. In every technical aspect, from the grainy texture of the image to the elliptical and fragmentary nature of the editing, a documentary manner is directly evoked, and in such a way that the narrative fiction, Ben (1) in his isolation, seems almost stumbled upon -– one tangled thread in a jumble of seemingly limitless actuality.

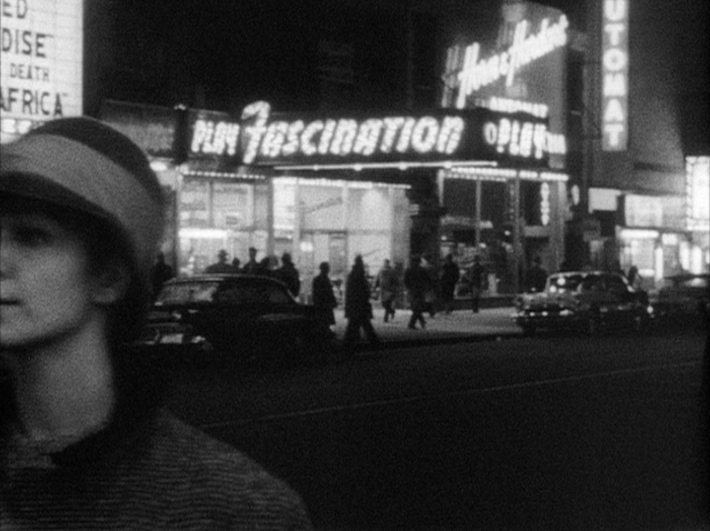

After a second sequence introducing Hugh at a rehearsal, the scene shifts to Hugh and Lelia at Port Authority Bus Terminal as he’s about to leave for a singing gig in Philadelphia. The gentle tension at work between siblings here is about whether she should take a cab home, a suggestion she rejects because she insists she’s old enough to take care of herself. After Hugh leaves, Lelia pauses to look at posters of Brigitte Bardot outside a Times Square theater until a man sidles up to her and grabs her arm (as if to bear out the wisdom of Hugh’s paternalistic warning about her walking home alone).

Another man —- recognizable as Cassavetes in a brief cameo – gruffly pushes the masher away, allowing Lelia to break loose and hurry off, and the shot ends after she has fled, with the camera focused ominously on the nearby Rialto marquee, which reads

Models by Day Playgirls by Night Girls Inc. She Stops at Nothing to Get What She Wants also Impulse

— a conclusion that, again, uses documentary to amplify the fiction.

This leads us logically enough to the opening of The Savage Eye, and a contrasting set of strategies in juxtaposing documentary and fiction. Here we begin with no characters or milieux in the ordinary sense, merely a plane arriving in the Los Angeles airport and glimpses of emerging passengers. Then two actorly presences take over and guide our attention in two separate and distinct directions — towards an abstract perception of the passengers in general, bolstered by the documentary look and context and by a disembodied male, quasi-authorial voice (that of Gary Merrill), and a concrete perception of one passenger in particular (the fictional Judith McGuire), played by actress Barbara Baxley, who crosses the airport and boards a bus. As the camera again seems to pick out one isolated thread from a tangle of actuality (a standard neo-realist approach), these two visual registers, documentary and fiction, become complemented by the two voices on the soundtrack, establishing a dialogue between these modes that, in contrast to Shadows, reduces the behavioral density of the characters and increases their sociological context and background through an offscreen literary text:

Merrill: Travelers by cloud –- uneasy, grateful, swung on a thread of exploding fire, they step down from heaven to the great sweaty footbound company of us all -– Alone, traveler?

Baxley: Alone.

Merrill: What’s your name?

Baxley: Judith.

Merrill: Judith what?

Baxley: Judith X.

Merrill: What’s the X?

Baxley: Ex-McGuire […]

Merrill: Alone, traveler?

Baxley: Alone.

Merrill: Why?

Baxley: Because the touch of human skin makes me sick.

Merrill: What’s his name?

Baxley: Who?

Merrill: Your ex-husband.

Baxley: Charles McGuire.

Merrill: How long did it last?

Baxley: Nine years, sixty-four days.

Merrill: Children?

Baxley: Killed.

Merrill: Killed? How?

Baxley: The usual way. Rubber, miscarriage, misconception, the knife….Who are you?

Merrill: I’m your angel. Your double. That wild dreamer -– your conscience. Your god. Your ghost….Where are we going?

Baxley: I don’t much care.

Merrill: To the past -– or the future? To the seven layers of Troy? To London burning by war? Or Rome, with the searchers of the catacombs? Or Athens, Los Angeles? Cities of the moon?

Baxley: Well, hardly. I only paid $1.25.

It’s a strained literary mode which seems to reflect the preoccupations and poetics of lapsed Catholicism, the voices bouncing back and forth at times like the queries and responses in a catechism. Significantly, the characters in this dialogue -– Judith and The Poet (as Merrill is identified in the credits) –- also suggest at times the disembodied voices in a tortured version of a confessional: the woman almost constantly visible, and acutely vulnerable in her visibility; the father-confessor-god-poet speaking safely and snugly from half-outside the fiction –- apparently seeing all, knowing all, and risking nothing.

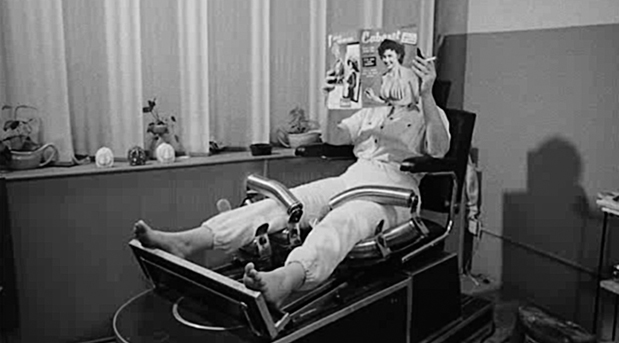

Sounding at times like T.S. Eliot strained through pulp –- and abetted by a remarkable performance from Baxley, and a Leonard Rosenman score whose abrasive atonality equally summons up a veritable anthology of purple prose-poetry read to mannerist 50s music (from Ken Nordine’s Word Jazz to June Christy and Stan Kenton’s “This is My Theme” to the collaborations of poets like Kerouac and Rexroth with jazz musicians) -– the commentary throughout The Savage Eye extends and clarifies the studied anti-humanism of the visuals, which, in keeping with the film’s title, tends to rely on the grotesque images of satire: a garishly opulent rotating cowgirl figure in front of a motel, a nosejob operation which is virtually contemporaneous with the one performed in Thomas Pynchon’s V., a little girl with false eyelashes in a hat store, a dog’s funeral. According to Joseph Strick (in an interview with Judith Crist in the New York Herald-Tribune, June 5, 1960). “Our first idea was Los Angeles as seen by Hogarth. The appurtenances have changed, but life is not so very different. Then we realized the parallel was too stretched for a film.”

Although The Savage Eye is cosigned equally by Strick, Ben Maddow, and Sidney Meyers, it appears from the same interview that Maddow was principally responsible for the script. The literary bent of Strick, however, should not be overlooked; at the time of the film’s New York release, he cited Ulysees and The Castle among his future film projects with Maddow and Myers, and regarding The Savage Eye, noted, “We’re hoping Sartre, Cocteau or Malraux will contribute to the French script. In Italy, we hope to get Carlo Levi or Ignazio Silone to do the soundtrack. In the Spanish version -– it’s the kind of thing you’d like Lorca to do if he were alive.”

The visible humanism of Meyers (as evidenced by The Quiet One, his previous film) and Helen Levitt, among other collaborators, seems a bit harder to reconcile with the film’s misanthropy — although the latter recently recalled, in a brief phone conversation with me, that little of her own work was used in the final version. (She mainly recollects going around with Strick and filming “everything that appealed to us,” including “a lot of oil pumps and places in Venice” and the dinosaurs in the Le Brea Tar Pits.) For Jonas Mekas, the film’s heartlessness could be accounted for geographically, like a documentary fact rather than like a state of mind:

…Perhaps the shadow-killing and all-leveling California sun affects one differently (which may also be the reason for what Hollywood really is) — basically, the West Coast filmmakers seem to take life as a plain, one-level phenomenon, without any shadows or nooks or corners. In this shadow-less sun all the proportions of life seem to have been bleached out. Death, Birth, Sickness, Sex — everything acquires the color of a wax museum. Even Sidney Meyers’ The Savage Eye, as it is, with its cynical detachment, can be explained only by the fact that it was shot in California. In New York the same scenes would have acquired a certain sadness, a certain humaneness. (“Cinema of the New Generation,” Film Culture No. 21, Summer 1960)

One might tentatively suggest that the influence of surrealism — no less prominent in the Los Angeles of Nathanael West — also accounts in part for this distance. But it is a distance enforced at least as much by the offscreen dialogue, the music, and the choice of subjects as it is by the images themselves. Doggedly anti-Hollywood in its negativity, the film nevertheless becomes no less ritualistic about its own assumptions — requiring, for instance, that all the heroine’s attempts at fulfillment are equally doomed. After attending a wrestling match with an older man named Kirtz (Herschel Bernardi), she is obliged by the didactic plot to stop off with him next at a strip joint, and a subsequent joyless New Year’s Eve party is followed just as mechanically by (a) the despair of off-screen sex and (b) the promise of redemption the morning after, accompanied by such images as Judith taking her car through a car wash:

Merrill: It’s Sunday morning–

Baxley: I know.

Merrill: You took a shower.

Baxley: Twice.

Merrill: You washed the bathroom, the kitchenette and the ashtrays.

Baxley: Around the clock.

Merrill: Why?

Baxley: I got a thing that won’t wash off — the slime of loveless love.

Merrill (with glib finality): Masturbation by proxy. (2)

Yet ironically, it is the privileged position assumed by this dialogue — and the corresponding denial of a prominent use of direct sound that would allow us to listen to the camera’s subjects — that makes some of the film’s images akin to some of those in pornography, provoking the basis for a kind of aesthetic masturbation whereby the roving “savage” eye becomes the equivalent to the stroking hand. Significantly, the film’s most powerful (and climactic) sequence, which immediately follows the above exchange — a faithhealing session conducted in a church that Judith visits on Sunday morning — is the only one in which the music and dialogue vanish, to be more than amply replaced by the sounds of the event itself. Here. for once, documentary triumphs over fiction and poetry, and the corrosive power of the images and sounds — the wailing anguish of faces and voices (mainly female) speaking in tongues and weeping, the droning reassurances of the preachers (all male) offering comfort — confounds any possibility of facile verbal and melodramatic paraphrase, and the film’s litany of suffering turns into a kind of aria that clearly needs no support.

Here and here alone, the effect towards which the entire film has been aiming is fully and devastatingly achieved in all its complexity, illuminating the religious context that is elsewhere evoked principally through the overheated dialogue. By contrast, the belated feelings of universal love expressed by Judith after she survives a freeway accident (e.g., “His candle burns for me”; “We’re all secret lovers of one another”) seem contrived and false, an unconvincing “New Testament” postscript to the dispassionate “Old Testament” implacability which precedes it. (“Could it be that we Americans overvalue Love ritualistically because we undervalue it actually?” Dwight Macdonald wondered in his review in the October 1960 Esquire.)

One of the most historically interesting aspects of The Savage Eye today is the degree to which it seems both ahead of and behind its own time in relation to modernism. While the commentary and score tend to remain just as dated and as “moderne” as they were in 1960, the iconographic surface of the film and certain other aspects (including the ethnographic detachment) are striking anticipations of images and ideas which would inform cinematic modernism over the following two decades. Set the offscreen voices of Merrill and Baxley alongside those of Godard and Marina Vlady, and the hat store and beauty parlor of The Savage Eye (among other settings and references) become startling approximations of the no less sociologically approached boutique and hairdresser in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her. The use of stream-of-consciousness — no less pronounced in Godard’s The Married Woman, where it is also juxtaposed with sociology — is equally evident. By the same token, the film’s fascination with car accidents parallels a comparable obsession in contemporary painting, sculpture, and fiction. Even the pitiless voyeurism towards (and through) sex, violence, and psychosis seems to echo certain attitudes and preoccupations in such varied writers and directors as Ballard, Beckett, Buñuel, Burroughs, Flannery O’Connor, Franju, Kubrick, Robbe-Grillet, and Nathanael West, while a brief, melodically fragmented atonal piano theme used for dramatic emphasis evokes a similar use of one in Antonioni’s Eclipse.

***

By contrast, the overall thrust of Shadows is resolutely premodernist — or, at least, modernist only in the sense that Method acting as derived from Stanislavsky and Chekhov continues to be modernist. Here, however, it is difficult to be authoritative, for we are essentially dealing with the second of two versions of Shadows, and the only one that has been available since 1960; and the earlier version was widely celebrated by Jonas Mekas as the superior and more modern of the two (3), a film whose relative rawness and lack of structure made it a significant early example of the New American Cinema. According to letters by Cassavetes and Carruthers which appeared in The Village Voice on December 16 and 30, 1959, the first version was screened at midnight at three successive non-admission screenings at the Paris Theater, attended by a total of about 2,000 people. Eight additional scenes were then shot for the second version after the first failed to acquire a distributor, and according to most accounts, the major change in the editing was an increase in continuity and conventional narrative structure. By necessity, we can only deal here with the second version — a document which is itself of major importance in the American cinema as a whole, and which has been woefully unknown to Cassavetes fans for far too many years.

A few words need to be said about the film’s inception. Cassavetes and director Bert Lane had organized a dramatic workshop held in a studio with a stage. One night, apparently, the late-night radio talk show announcer Jean Shepherd visited one of their sessions and was especially impressed with an improvisation which took place between actors, during which a young man (Tony Ray, the son of film director Nicholas Ray) discovers that his girlfriend (Goldoni) is black when she greets her dark-skinned brother (Hurd). Shepherd invited Cassavetes to appear on his show Night People, where the latter described his workshop and his desire to film their work if he could raise enough money, inviting listeners to pledge their support. According to Hurd (in an interview with Clara Hoover in Film Comment), $2500 was raised within a week’s time. (The final cost of the release version was estimated at around $40,000, and Cassavetes later remarked it was “three years in the making”. The Savage Eye, which cost $65,000, required four years of work over weekends.) And once started from this encouragement, the film grew as a collective improvisation out of the scene that Shepherd had witnessed.

Shadows‘ improvisational method and collective authorship are as closely linked as these attributes are in subsequent films co-signed respectively by Jacques Rivette and Robert Altman; so it is scarcely surprising that group interactions and intimacies of various kinds — between family members, friends, couples, and associates — quickly become the very subject and substance of the film. The Savage Eye, on the other hand, essentially rejects the group for the individual or the abstraction (sociological or poetic), and the overcomposed commentary makes the film — for all the documentary immediacy of much of its footage — seem like the reverse of improvisation.

A crucial distinction must be made about the films’ immediate impacts and the different standards of judgment that these impose. Thanks to the brilliance, attractiveness, humor, and courage of such actors as Hurd, Rupert Crosse, Goldoni, Ray, and Carruthers, it is possible (and often tempting) to love Shadows for its flaws as well as its triumphs, much as one can admire the risks and wayward inspirations of the best jazz players. Considering the subtle yet crucial fact that the film’s racial theme is scarcely alluded to at all in the dialogue, although it is frequently central to the action, an extraordinary amount of sensitivity and vulnerability permeate these rare performances. (4)

Signs of this range from effective cornball Method riffs — like Tony pausing just a beat between two words in his seduction of Lelia (“You’ve got the softest lips I’ve ever…felt”) — to subtle interplay between Hugh and Rupert, so delicately and sweetly nuanced that it becomes a veritable lesson in ways that people can behave decently towards one another. (At the other end of the spectrum is the crude, anti-intellectual bullying assigned to Lelia’s hapless writer friend David Pokitillow, whose improbable “literary party” — a satire of sexual come-ons, hangups, and cultural pretensions which would eventually lead to much finer observations in Cassavetes’ Faces — is equally unconvincing.)

Regarding the incestual feelings that are touched upon in the siblings’ scenes together, it is easy to be reminded of J.D. Salinger’s Glass family, another team of (professional and unprofessional) neurotic New York actors. But the warmth of Cassavetes’ family goes much further — past racial barriers and class snobberies, and without specious references to clichés of suffering humanity like the Fat Lady of Franny and Zooey (who surely belongs more in the menagerie of The Savage Eye, along with the suicidal Seymour Glass). The mutual affection shown between Hurd, Goldoni, and Carruthers (and between Hurd and Crosse, where the closeness is almost familial) is a potent ingredient in all their scenes together, and winds up surviving every other social bond in the film — including that of Bennie and white pals Dennis (Sllas) and Tom (Allen), whose aimless exploits with women frame the main action of the film, and whose cohesion seems to dissolve at the end, after they lose a brutal fight with another male trio, returning Ben to his loneliness.

This sense of human closeness, recalling at times the ambiance of early Truffaut films made around the same period, culminates in the long scene staged around and on Lelia’s bed — where the two brothers become virtual rivals for her affection — and the final visit paid to their flat by Tony, just as Lelia is leaving with a black date. This leads to a reversal of roles between Bennie and Hugh, with the former suddenly becoming the voice of tact and reason as he decorously gets rid of Tony — a beautiful scene of dawning recognition where Tony’s own square form of repentance becomes the catalyst for the brothers’ own mutual expressions of love and forgiveness. It is at such moments (and there are others) that Shadows shows its true documentary colors — creating and recording its own kind of love on the screen.

Notes

1. The actors’ use of their own full names in Shadows -– curtailed only by the avoidance of surnames for Benny, Hugh, and Leila –- which further extends the illusion that all three are blood relatives (when in fact they aren’t, and Goldoni is entirely white), naturally carries the documentary aesthetic further, and invests their improvisation with existential significance, an acting and playing out of their own identities. By contrast, the actors in The Savage Eye play out wholly assumed identities.

2. All the transcriptions of dialogue in the film used in this article were made by the author.

3. I was fortunate enough to have been one of the few people who were able to see the original Shadows after its was recovered by Ray Carney (and before it became inaccessible due to legal problems) at one of its two screenings at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in February 2004. For further details about this version, go here. [2010]

4. Apart from the important hint offered by the title, and the implicit context of Charles Mingus’s wonderful score — which culminates in a rousing version of the “Haitian Fight Song,” conceived explicitly by its composer as a response to race prejudice — there’s a pointed line delivered by Hugh to his lighter-skinned brother about Lelia’s crisis with Tony: “Look, Bennie, it’s just a problem of the races. Like I said, it’s nothing you’d be interested in.” On a visual level, two separate closeups of the thumbs of Hugh and Tony ringing the door buzzer of the family’s flat in different scenes spell out the only racial message that’s needed at each point.