From Sight and Sound, Summer 1986 and my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles. For the first half of this article, and a detailed account of how it came to be written, please go here.

In my synopsis of The Big Brass Ring, I erroneously identify Kim Meneker’s former lover as “a basket-case casualty from Vietnam” rather than from the Spanish Civil War. –- J.R.

THE DEEP.

Not to be confused with Peter Yates’s 1977 feature of the same title, this adaptation of Charles Williams’s thriller Dead Calm, scripted by Welles, was shot in color off the Dalmatian coast at Hvar, Yugoslavia, between 1967 and 1969, with Welles, Laurence Harvey, Jeanne Moreau, Oja Kodar and Michael Bryant. Most of this film was shot and edited, but gaps remain due to the death of Laurence Harvey in 1973 and the still undubbed part of Jeanne Moreau. Welles, Kodar and others have regarded this as the least of his features, so one imagines that it has a low priority on the list of works to be completed and/or released — although, as Kodar points out, priorities may change on any project if investment is forthcoming.

At the Rotterdam film festival last January, Kodar, Dominique Antoine and I compiled a 90-minute videotape of Wellesiana to be shown there, and among the clips we included was a two-minute trailer for The Deep — an early action sequence including brief glimpses of all five of the characters on two yachts and an effective use of percussive jazz (bass and drums) on the soundtrack. Crisply if rather conventionally edited, it does not suggest major Welles, although a look at Williams’s novel suggests an intriguing tension between the characters of Hughie Warriner (Harvey), a psychotic hijacker, and Russ Brewer (Welles), an acerbic macho writer, which in some ways parallels the charged relationships between older and younger men in Chimes at Midnight, The Other Side of the Wind, and The Big Brass Ring. (If the theme of mothers and sons seems to inform the early features — Kane, Ambersons, The Lady From Shanghai, Macbeth — the emphasis on fathers and sons seems no less prevalent in some of the later projects.)

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE.

The most unknown of all Welles’ invisible features, shot in color (by Giorgio Tonti, Ivica Rajkovic and Tomislav Pinter) in Trogir, Yugoslavia, Asolo, Italy (the villa of Eleonora Duse), and Venice in 1969. The film was completed — edited, scored and mixed — over fifteen years ago but has not yet seen the light of day because two of the work print reels, including the sound elements (which are now missing from the original negative) were stolen from the production office in Rome.

The last of Welles’ realized film adaptations of Shakespeare, featuring himself as Shylock, Charles Gray as Antonio, and Irina Maleva as Jessica, it is set in the 18th century and, according to Kodar, reflects Welles’ interest in Judaism, as well as his belief that the play is neither anti- nor prosemitic. “It’s impossible to believe that [Shakespeare] didn’t know Jews,” Welles told Bill Krohn in 1982, during the interview in which he first acknowledged the film’s existence. “And there were few of them in England at the time. But there was the theory that he’d been in the Low Countries and doing military service, and it would have been there that he’d run into a lot of Jewish people. Because the rhythms of speech are so Jewish.” (It is worth noting that in The Dreamers Welles also cast himself in an explicitly Jewish role.)

Welles originally wanted Kodar to play Portia, but she refused, at that stage considering her English inadequate, and Welles wound up eliminating Portia from the story altogether — a startling move, but one not inconsistent with some of his other drastic changes in Shakespeare throughout his career. One of the segments planned for Orson Welles Solo was an abridged one-man performance of Julius Caesar eliminating Brutus!

The F FOR FAKE Trailer.

Before the disastrous American release of Welles’ 1973 feature (but after its successful run in Europe), he filmed a promotional trailer with completely new material, featuring Kodar and Gary Graver. Because the film runs about a dozen [nine] minutes, the American distributor indignantly refused to process it; it remains in black and white work print form, with sound and image on separate reels, and was shown in that form at a Welles tribute in Los Angeles a few years ago.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND.

If Don Quixote has the longest production history, this color and black and white feature, prefigured to run about three hours, has certainly had the most complex and nightmarish vicissitudes; Kodar has remarked that the correspondence file alone is as long as War and Peace. (See the lengthy account in Leaming’s biography, which co-producer Antoine informs me is entirely accurate.) Started well before F for Fake, in 1970, and continued for years afterwards, in Arizona, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, the film was very nearly completed: Antoine recalls Welles putting together a rough cut with the aid of no less than eleven moviolas, arranged in a semi-circle. But for the last decade it has remained unseen, either in the possession of the brother-in-law of the late Shah of Iran or in the French courts, where Kodar is trying to retrieve it, hoping to complete it with the assistance of Graver (who shot the entire film and worked on the editing) and Peter Bogdanovich. From all accounts, it would appear to be both Welles’ last satiric word on the world of cinema and one of his most adventurous stylistic experiments.

“When we started writing the script,” Kodar says, “we had two stories. Orson’s was called Jake Hannaford and it was too long, because it was based on the life of movie director Rex Ingram, and on Hemingway following the bullfights through Spain, and on some of Orson’s own experiences. Orson came to the conclusion that the bullfights had become just a tourist attraction and had lost whatever sincerity they once had.

“So after he discovered his script was too long, and cut everything he wanted to cut, he discovered it was too short. This is how we decided to make a sort of osmosis of his story and my story, and began working together on a new script. My story is that there is a man who is still potent — it’s not that he is impotent — but gets a real kick from the idea of sleeping with his leading man, sleeping really with the woman of his leading man. So he is not a classic homosexual, but somewhere in his mind he is possessing that man by possessing his woman. And at the same time, just because there is a hidden homosexuality in him, he is very rough on open homosexuals, as so many of those guys are.

“This is one reason why the script is so complicated and has so many chords. When you see the film, you will feel that somebody else worked with him because there are things that he never would have done alone, and never did before. He was a very shy man, and erotic stuff was not his thing. And in this film, you will see the erotic stuff. He kept accusing me with his finger: ‘It’s your fault!’ And he was right — it’s my fault!”

Part of this film’s formal interest is that it incorporates two separate styles, neither of which can be associated with Welles’ customary signature (apart from the almost subliminally rapid editing which characterizes his “late” manner from Othello to portions of The Trial to F for Fake). One style belongs to an unfinished, rather arty film which Jake Hannaford (John Huston) is screening at his birthday party; the other derives from the diverse 16mm, Super-8 and video footage being shot by several TV and documentary crews at the party.

Centered round the night of July 2nd (which, Joseph McBride has noted, “is not coincidentally the date of Hemingway’s suicide”), and reportedly employing a somewhat Kane-like flashback structure, the film features TV actor Bob Random as Hannaford’s leading man, Kodar as his leading actress, Lilli Palmer as the friend giving the party, Peter Bogdanovich as a younger director (patterned in part after Bogdanovich himself) and, among others, Norman Foster, Curtis Harrington, Henry Jaglom, Joseph McBride, Mercedes McCambridge, Paul Mazursky, Cameron Mitchell, Edmond O’Brien, Paul Stewart, Susan Strasberg, Dan Tobin, and Richard Wilson. Two excerpts from the film — both witty and frenetic — were shown by Welles at the AFI’s Life Achievement Award banquet held in his honor in 1975, in an unsuccessful attempt to raise completion money, and these are described in some detail in the closing pages of James Naremore’s excellent The Magic World of Orson Welles. Which affords us a match cut to

THE MAGIC SHOW.

Shot intermittently between 1969 and 1985 with Graver, Kodar, and fellow magician Abb Dickson, in Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Kodar’s home in Orvilliers, France, this is the project Welles was working on when he died. The centerpiece of this theatrical smorgasbord, which seems to bear some resemblances to Tati’s Parade, is an assortment of some of his best acts of prestidigitation, all done without camera tricks. According to Graver, this portion of the program runs about half an hour and is more or less edited. The remainder consists of The Orson Welles Special, completed, a 90-minute talk-show with Burt Reynolds, Angie Dickinson, and the Muppets; and Orson Welles Solo, scripted but regrettably unrealized, which Welles wanted to shoot partially with a Betacam — a one-man show that would have included the abridged Julius Caesar without Brutus and the telling of an Isak Dinesen story, “The Old Chevalier,” which Welles had originally planned to include as part of a sketch feature for Alexander Korda in the 1950s, Paris by Night. Other cast members in the magic show as a whole include Senta Berger, Artie Johnson, Lynn Redgrave, Mickey Rooney (whom Welles once expressed an interest in casting as the Fool in King Lear), and restaurateur Patrick Terrail.

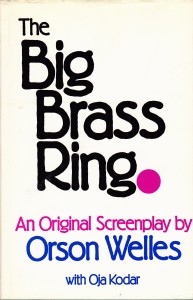

THE BIG BRASS RING.

Although this project never got beyond the script stage, it is unquestionably one of the most remarkable and revealing works in the entire Welles canon. Written at the urging of his friend director Henry Jaglom, ostensibly as a “commercial” Hollywood screenplay, it is in fact nothing of the sort — though no less brilliant for that. The

settings are New York, a yacht in the Mediterranean, North Africa, Barcelona, and Madrid. Senator Blake Pellarin, a Texas Democrat, has just lost out to Reagan in a presidential election, to the bitter disappointment of his ambitious wife, Diana. On a yachting trip, he spies a Portuguese maid about to steal his wife’s emerald necklace and impulsively urges her to take it. Then, even more impulsively, he offers to find her a fence for it, snatches it back, and sets off on a wild goose chase leading him to his beloved Harvard mentor Kimball Menaker (Welles), holed up at the Batunga Hilton with a sickly, dying pet monkey and two black, nude female bodyguards.

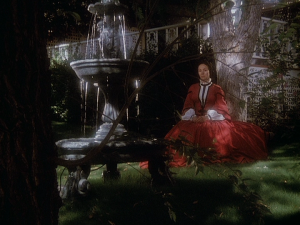

Having thus in effect gone AWOL from his wife and political entourage, Pellarin asks for Menaker’s help in fencing the necklace, which eventually leads to secret meetings between the two in Madrid. As the story shuttles in Arkadin-like fashion between Pellarin, wife and entourage, and Menaker, and their occasionally parallel trajectories, the major go-between is Cela Brandini, a jet-set journalist in army fatigues clearly patterned after Oriana Fallaci [see above photo]. Rather like the faceless reporter in Kane, she probes the painful half-secret that has helped to undo Pellarin’s political career and continues to bind him to Menaker — the fact that Menaker, once a prized member of F.D.R.’s Brain Trust, has belatedly come out of the closet and, in a letter to his former lover, now a basket-case casualty from Vietnam, declared his love and lust for Pellarin.

The above barely summarizes the plot’s point of departure, but cannot begin to do justice to the manic energy of this demonic, tragicomic thriller, which Welles hoped to shoot in black and white. (Most of the members of Pellarin’s entourage are comic grotesques worthy of the Grandi clan and night watchman in Touch of Evil.) Shortly after Welles’ death, Jaglom complained bitterly to the Los Angeles Times about the circumstances which sank the project. Producer Arnon Milchan agreed to put up the money if Jaglom and Welles could find a bankable star to play Pellarin for two million dollars, but all seven of the stars who were approached — including Warren Beatty, Clint Eastwood, Jack Nicholson, Robert Redford, and Burt Reynolds — turned them down, each for a different reason.

The script manages to convey complex feelings about Spain since the Civil War and the U.S. from the New Deal to Watergate, as well as a Goyaesque view of powerless and helpless suffering (which “rhymes” Menaker’s pet monkey with a blind beggar whom Pellarin kicks to death), and a delirious depiction of sexuality which comes to the fore in Pellarin’s reunion with a former Vietnamese mistress (another contribution by Kodar of “erotic stuff”). Overall, the plot gradually develops from a kind of bouncy naturalism to a nightmarish phantasmagoria, before returning to mischievous comedy. It is clearly too advanced, too sophisticated, and too candidly personal for anything that Hollywood in the 80s could begin to handle, much less imagine. Forty years earlier, Welles had RKO and all its resources at his disposal; with a fraction as much today, he might well have come up with a feature just as startling.

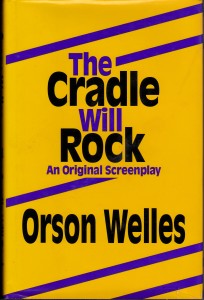

THE CRADLE WILL ROCK.

Like Touch of Evil, this was a project not initiated by Welles, but one which he was able to take over after it had been developed separately — in this case, scripted by Ring Lardner Jr. for producer Michael Fitzgerald. According to Kodar, Welles’ version of the script, written during the fall of 1984, was entirely original.

Set in New York City and environs in 1937, The Cradle Will Rock depicts Welles’ life and career at the age of twenty-two: performing Dr. Faustus on Broadway, meeting composer Marc Blitzstein and launching his leftist musical The Cradle Will Rock, and meanwhile performing weekly on radio shows ranging from The Shadow to soap operas to The March of Time, proceeding from one studio to the next in a rented ambulance. The plot is candid enough to comment on some of the problems in Welles’ first marriage as well as his ambivalent relation to Blitzstein’s radical politics. Members of the Mercury Theatre such as John Houseman, Augusta Weissberger, black actor Jack Carter, and Welles’ first wife, Virginia Nicolson, figure prominently; and the script begins with Welles himself as narrator, succinctly evoking the mood of the Depression of the mid-30s.

After Welles cast Rupert Everett as the young Welles and Amy Irving as Virginia, sets were constructed at Cinecittà in Rome and exterior locations selected in New York and Los Angeles; but three weeks before shooting was scheduled to begin, the budget evaporated after some difficulties between the investors. Tragically, not even Steven Spielberg, Amy Irving’s husband, who once paid a princely sum to purchase one of the original Rosebud sleds, was willing to lift a finger to save the project.

Apparently Fitzgerald is still interested in filming Welles’ script, with another

director. A fascinating and highly critical self-portrait, it tells a lively story whose interest goes well beyond its autobiographical aspects in its nostalgic evocations of the period. Whether a film of the script could overcome the problem of casting young actors as Welles, Agnes Moorehead, and other Mercury figures without alienating older viewers remains an open question (Welles himself was apparently concerned about this issue). But for any reader of the script who can fill in the names with the appropriate faces, it remains an exciting and crucial document — possibly the most extensive exercise in literal self-scrutiny that Welles has given us. And considering the over-40-year feud between Welles and John Houseman, it is worth noting that Welles’ depiction of his Mercury producer is in fact rather benign; the script even paraphrases Houseman’s description of Welles as a Faustian obsessive in his memoir Run-Through — a view hotly contested in Leaming’s Welles biography.

KING LEAR.

I haven’t read Welles’ screenplay for the last of his projected adaptations of Shakespeare, which he planned to shoot in black and white, with himself as Lear, Kodar as Cordelia, and Abb Dickson (the magician in The Magic Show) as the Fool. But going by Kodar’s description, it is a good deal more detailed than the other scripts which I have read — indicating every move of the camera and actors, and supplemented by many drawings for the costumes and constructed models for the sets. And Welles’ proposal for Lear in the form of a six-minute videotape, shown in Rotterdam last January, gives provocative and tantalizing clues about the form and style that his film would take.

After powerfully evoking the play’s theme of old age, he begins to describe what the film won’t be like. It will not, he promises, be “what is called a costume movie” in any sense of the word. “That doesn’t mean that the characters are going to wear blue jeans; it does mean that a story so sharply modern in its relevancy, so universal in its simple, rock-bottom humanity, will not be burdened with the time-worn baggage of theatrical tradition. It will be just as free from the various forms of cinematic rhetoric, my own as well as the others, which have already accumulated in the history of these translations of Shakespeare into film. What we’ll be giving you, then, is something new: Shakespeare addressed directly and uniquely to the sensibility of our own particular day. The camera language will be intimate, extremely intimate, rather than grandiose. The tone will be at once epic in its stark simplicity and almost ferociously down to earth. In a word, not only a new kind of Shakespeare, but a new kind of film.” Conceived of largely in close-ups, Welles’ Lear, one imagines, would have been a logical successor to Chimes at Midnight.

Although Lear was ostensibly to have been financed by French television, Kodar firmly believes — as did Welles — that they never sincerely intended to make the film. Speaking in a barely controlled rage at the Directors Guild tribute to Welles last November, she read a cable of condolence from François Mitterrand stating that Welles “may not have been able or may not have wanted to have followed to an end this film.” “I am sorry,” Kodar then remarked, “that M. Mitterrand, even at this sad

hour, has had to play politics and defend his establishment. . . . Who would be the best person to help French Minister of Culture Jack Lang to take his foot out of his mouth for openly declaring his dislike and disdain for existing imperialism of nonexistent American culture? Who else? Welles.”

Speaking of an artificially inflated budget, impossible production conditions, and broken promises, Kodar read the last part of Welles’ own message to Paris in May 1985: “In the fifty-five years of my professional career I have never, not even in the worst days of the old Hollywood, encountered such a humiliating inflexibility. Need I say that this is a bitter disappointment to one who has until now received so much heartwarming and generous cooperation in France. To my profound regret, therefore, I must accept that your own last Telex is the last word about Lear and that there is no longer any hope that in this affair a constructive relationship is possible.”

Despite this loss of finance, Welles continued to hope to make the film by other means, and had himself photographed in his Lear costume and makeup shortly before his death [ see Gary Graver test, above].

THE DREAMERS.

“The last of Orson’s dreams,” Kodar describes this color adaptation of two Isak Dinesen stories, worked on between 1978 and 1985. While trying unsuccessfully to raise money for this project, Welles shot various tests and a few scenes, totaling about twenty minutes, in and around the house he shared in Hollywood with Kodar, with Graver as cinematographer and Kodar in the lead part of Pellegrina — an

opera singer who, having lost her voice, decides to live many other lives. In the first story, “The Dreamers,” three men who have fallen in love with her — a young Englishman, a Danish cavalry officer, and a young American — converge on an inn, each in search of her, and during a blizzard pass the time by telling one another about their affairs with this elusive woman, only gradually discovering that they are all in pursuit of the same person. In the second story, “Echoes,” Pellegrina arrives in a remote mountain village, and, in a church, encounters a young boy named Emmanuele whose singing voice seems identical to the voice she once had. She proceeds to give the boy voice lessons and falls in love with him, until he denounces her as a witch.

In the earliest version of the script, entitled Da Capo, Welles introduces the film by speaking of his lifelong infatuation with Dinesen’s work. In the last version, the introduction is given over to Warren Beatty, who introduces Welles, who introduces in turn Lincoln Forsner, the young Englishman in search of Pellegrina — who is himself only the first of many narrators in Welles’ intricate Chinese box structure of tales within tales.

Probably the most romantic of Welles’ late projects, The Dreamers would almost surely have embodied his most exquisite and developed use of color. Over two years in Madrid, still photographer José Maria Castellvi worked as Welles’ “color scout” by photographing precise changes in the colors of the leaves in a park at different times of day and recording the time and date of each photograph, all in preparation for sequences to be shot in Spain. (Shortly before Welles’ death, Castellvi told me, a trunk arrived containing all the costumes to be worn by Kodar.) A three-minute scene filmed in 1982 in Welles and Kodar’s backyard in Hollywood, describing Pellegrina’s departure from her life as a famous opera singer, represents as much of a quantum leap from The Immortal Story, Welles’ previous Dinesen adaptation, as Othello does from Macbeth. Admittedly, the scene is no more than an unfinished fragment: Welles never got round to shooting his own close-ups (in the part of Marcus Kleek, the elderly Dutch Jewish merchant who is Pellegrina’s only friend), and the dialogue — a lovely duet of two melodious, accented voices, accompanied by the whir of crickets and even the faint hum of passing traffic — is recorded in direct sound. But the delicate lighting, lyrical camera movement, and rich deployments of blue, black and yellow, combined with the lilt of the two voices, create an astonishing glimpse into the overripe dream world that Welles envisioned for the film.

***

As suggested earlier, the above list is far from exhaustive; but clearly it is more than enough to vindicate Welles from the charge of idleness in his late years. The range of the work is as remarkable as the breadth, and the fact that virtually all this legacy has remained buried gives the film industry and media a lot to answer for. But a tentative hypothesis or two about how this happened might help to shed some partial light.

A man who was deeply moved when he was once recognized as Falstaff (rather than as Orson Welles) by a driver on the Champs-Elysées, Welles felt he belonged more to the public than to the film specialist. After the fame that carried him through his mid-twenties, conceivably the most galling aspect of his subsequent career was the lack of a clear mainstream success. The only time that I met him, in 1972 — having unexpectedly been invited to lunch by him in Paris two days after writing a modest

letter of inquiry about Heart of Darkness, his first feature film project — I was surprised to hear him say that he was reluctant to release Don Quixote then because he didn’t want it to compete with Man of la Mancha. No less surprising was the discovery that not even the earliest of his film dreams, Heart of Darkness, was regarded by him as abandoned; he still nurtured hopes of making it one day. Yet as the projects accumulated and the investments dwindled, he steadily refused to accept the status of a marginal artist — a decision which undoubtedly spurred his creative activity at the same time that it edged him further and further away from the mainstream, except as an entertainer.

Thus, even while his work grew more inward and self-reflective in its resonance for Welles fans — with characters as diverse as Russ Brewer, Don Quixote, Shylock, Hannaford, Pellarin, Menaker, Lear, Pellegrina, and Kleek all taking their places beside the direct self-portraits in F for Fake, Filming Othello, and The Cradle Will Rock — the conscious address grew ever more expansive and generous in its appeal to the general public. This discrepancy may finally have less to do with Welles than with the shrinking and diminishing culture around him; but whatever its source, it could only be judged one way while he was alive — as creative blockage. Ironically, now that he is dead, the floodgates can open — demonstrating once again that what a culture wants of an artist at any given moment may at best be only incidental to the range of his or her talents.

As we know now from Leaming and Higham, Welles grew up trying to please parents who were diametrically opposed and eventually became estranged from one another, both of whom expected him to be entertaining and “grown up.” Considering how well he succeeded with both of them, it is scarcely surprising that he extended these talents to the outside world, which initially rewarded him no less handsomely for his deceptions. Like Pellegrina, he became more than the sum of his roles, even if his public career afforded him less than the sum of his reputation.

With this background in mind, the standard objections to Welles’ “character” remind one of René Clair’s fatherly advice to Preston Sturges, cited and admirably glossed by Manny Farber and W. S. Poster: “Preston is like a man from the Italian Renaissance: he wants to do everything at once. If he could slow down, he would be great; he has an enormous gift, and he should be one of our leading creators. I wish he would be a little more selfish and worry about his reputation.” “What Clair is suggesting,” note Farber and Poster, “is that Sturges would be considerably improved if he annihilated himself.” This is more or less what we tended to expect from Welles, and although it took him the better part of seventy years, he finally obliged us.

There are only two things it is ever seemly for an intelligent person to be

thinking. . . . One is: “What did God mean by creating the world?” And the

other? “What do I do next . . . ?”

— The end of The Dreamers