From Sight and Sound, Summer 1986 and my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles (the source of the following notes in italics as well).

I was living in Santa Barbara when Welles died on October 10, 1985, teaching what I believe was the first of the three Welles courses I taught at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and lecturing on The Magnificent Ambersons that same day. On November 2, I attended a lengthy Welles tribute held at the Directors Guild in Los Angeles, and recall sitting with a few other Welles fans, including Todd McCarthy and Joseph McBride, at a restaurant for many hours afterwards, holding what amounted to a kind of personal wake.

This wasn’t long after I’d managed to read and acquire xeroxed copies of two late, unrealized Welles screenplays, The Big Brass Ring and The Cradle Will Rock, and one of the idées fixes I had after his death was that both of them should be published, along with the Heart of Darkness script (another fixation that had persisted since the early 70s); if memory serves, I even wrote a letter soon after Welles’ death to Paola Mori, Welles’ widow, expressing this wish, but never got a response. Around November or December, I received a call from the Rotterdam Film Festival, which I had started attending regularly in early 1984, asking me how they could get in touch with Agnes Moorehead, Joseph Cotten, and other Welles associates in order to invite them to a Welles tribute they wanted to put together for late January. After explaining that Moorehead had passed away over a decade earlier, I did my best to persuade them that Oja Kodar, Gary Graver, and Peter Bogdanovich — all three of whom I’d just seen speaking at the Directors Guild — were the sort of people they should be inviting.

Meanwhile, knowing that my friend Bill Krohn had recently interviewed Kodar for Cahiers du cinéma and was still in touch with her, I enlisted his help as a go-between, and in fact owe it entirely to him and his persistence that she was persuaded to attend. Bogdanovich, who was going through a bankruptcy at the time, reported back that he could only attend if his accountant came along, which caused the festival to demur, and I don’t recall whether we ever got around to contacting Gary. I also gathered several videos and audiotapes of Welles materials to bring with me to the festival, including a professional taping of the entire DGA tribute that came courtesy of Richard Wilson. What I didn’t realize, however, until I arrived in Rotterdam, a few days ahead of Oja, was that Huub Bals, the festival director, was expecting me to produce the tribute.

Oja arrived at the Rotterdam Hilton with Dominique Antoine, the French producer of F for Fake and The Other Side of the Wind, as well as a few videos of her own containing Welles material, and it was quickly decided that the festival would drive the three of us to an editing studio in Amsterdam to put together a 90-minute compilation that could be presented towards the end of the festival’s ten days. And by the time we made our presentation a few days later, Oja had also gotten the festival to bring another friend, José Maria Castellvi, a Spanish still photographer who had taken some production photos on The Other Side of the Wind.

During the same few days, while becoming acquainted with Oja, I tried unsuccessfully to broker a deal whereby Râúl Ruiz, an ardent Welles fan who was also attending the festival, could film Welles’ screenplay for The Dreamers in a way that would incorporate the footage that Welles had already shot. Unfortunately, the Ruiz feature that happened to be showing at the festival, L’éveillé du pont de l’Alma, proved to be a less than ideal résumé as far as Oja was concerned, and she and José Maria lasted only about a third of the way through it.

Above all, it was my conversations with Oja (with Dominique’s input) over several days in Rotterdam that yielded the following article and also paved the way for our three eventual joint publishing ventures: The Big Brass Ring, The Cradle Will Rock, and This Is Orson Welles (the first two at my instigation, the third at Oja’s). But in the short run, once I was back in Santa Barbara, I first had to cope with a couple of disappointments. After writing the article and making an appointment with Oja to show it to her for her approval, I drove the hundred miles to her house on Stanley Avenue in Los Angeles, the one she had shared with Welles, one Sunday morning only to find an apologetic note from Oja on the front gate saying she’d had to go out to meet with her lawyer. (I left behind my draft, and she conveyed her comments and minor corrections somewhat later, over the phone.) And a plan for Oja to attend the Santa Barbara film festival, where I was presenting the same compilation video that we’d edited with Dominique, was also canceled at the very last minute. I wound up regarding both incidents as loyalty tests of some kind, even if they may not have been consciously intended as such — comparable to the sort of things that Welles himself had often done — so I made a point not to raise a fuss about them.

Some corrections and updates: The 16mm reels of Moby Dick alluded to here proved to be not Welles’ (unfinished and aborted) film of his English stage production but a subsequent incomplete solo performance of that play with Welles playing all the roles, shot by Gary Graver in Orvilliers (where Welles lived with Oja at the time) in 1971. Life of Lollobrigida proved to be only the working title of Viva Italia!, shown in its entirety under the latter name on German television a few years ago. For more material on Don Quixote, see the final chapter of Discovering Orson Welles. The obstacles preventing a completion of The Deep have included the failure of Jeanne Moreau to dub her own part, the disappearance of an edited work print, and the loss of other materials due to unpaid lab costs, though the Munich Film Archives have put together a feature-length restoration with a good many patches that are either silent or with live (as opposed to dubbed) sound and/or stretches in black and white. The mysterious missing reel of The Merchant of Venice remains unrecovered, although theories and rumors about its whereabouts continue to circulate. The F for Fake trailer is nine minutes long, not twelve. And the principal obstacle to completing The Other Side of the Wind [as of 2007], despite many attempted deals, has been the inability for Oja to obtain a contract allowing herself and Gary Graver to have final creative control. Given Gary’s shooting of the entire film and Oja’s substantial input as writer, actress, and even director (in a climactic sequence of the film-within-the-film), I consider them the only ones with the knowledge and sensitivity as well the moral right to carry out this work, but other egos and power positions have periodically argued otherwise.

In the spring of 1999, shortly after the Munich Film Archives acquired the unfinished and other film material of Welles that was then in Oja’s possession (not including Don Quixote, which had by then already gone to the Filmoteca Española in Madrid, or, in the case of other materials, remained with Mauro Bonnani in Rome or with the Paris Cinémathèque), I had the rare privilege of coming to that city (for the first time) at the invitation of Robert Fisher-Ettel and spending six days with him and other Archive employees going through a good many reels of film on flatbeds, assessing as well as we could part of what was there, and meanwhile helping to plan a four-day Welles conference to be held in Munich half a year later. (One of the first and most delightful discoveries I made on that visit was that Jakob Zouk’s attic in Mr. Arkadin was actually located across the street from the site where the Archives would later be built — purely by coincidence. Although the building has since been rehabbed, it remains recognizable.)

Among the many things that we looked at — including several reels from The Deep without sound and the unedited Filming “The Trial” — was The Magic Show, and Robert arranged to copy all of The Magic Show material for me on video so I could present a very tentative “rough cut” at the conference. My reasoning was that because Oja would be there, this crude assembly, which I put together in Chicago with two VCRs over the ensuing months, could trigger enough of her memories about the project to evoke corrections and other key indications about the intended order of sequences. But this strategy failed completely, because Oja was so distressed by the visual quality of the dubs that she promptly walked out of the auditorium shortly after my presentation started. Many months later, Stefan Drössler, who had meanwhile taken over Robert’s (temporary) position as director of the Archive, put together a shorter assembly of his own, on film, and I regret that he omitted my favorite part of the footage — a hilarious stretch of silent slapstick featuring magician Abb Dickson as a Southern sheriff, preceded by a brief monologue from him — because there was no obvious place for it in the performances of magic tricks. More recently, the young American Welles scholar Peter Tonguette has been researching The Magic Show, The Dreamers, and other late projects much more thoroughly via interviews for a book scheduled to appear before this one. (Portions of this work have already appeared in the online journal Senses of Cinema.) At the Locarno Welles conference in August 2005, Dickson accompanied the silent footage with his own clarifying commentary, and revealed that Welles had left other portions of the footage with him as well as some script materials. (At the same event, I resaw a roughly half-hour assembly of the materials shot for The Dreamers, which I continue to find the most effective and convincing of all of the Welles restorations carried out by the Munich Archive — material I even prefer in some ways to The Immortal Story, despite its unfinished and incomplete state.)

In my synopsis of The Big Brass Ring, I erroneously identify Kim Menaker’s former lover as a “basket-case casualty from Vietnam” rather than from the Spanish Civil War. — J.R.

The Invisible Orson Welles: A First Inventory

All films today are unfinished — except, possibly, those of Bresson.

— Râúl Ruiz in conversation

You don’t imagine that posterity’s judgment, do you? Posterity is a

whim. A shapeless litter of old bones: the midden of a vulgar beast: the

most capricious and immense mass-public of them all — the dead.

— Kim Menaker in The Big Brass Ring

It seems typical of the misunderstandings which plagued Orson Welles’ life that he died, as a working artist, in almost total obscurity. The director of Citizen Kane, to be sure, taped a lengthy TV talk-show appearance the day before he died which summarized a substantial portion of his career — as magician, actor, director, one-time political aspirant, show-biz personality, and, most recently, the subject of a biography by Barbara Leaming. Yet such is the nature of our media and its discreet omissions that this generous glimpse of Welles failed even to hint at the artistic activity that consumed the last two decades of his life. The closest the program got to this reality was a passing acknowledgment of Chimes at Midnight, released in 1966, as an unjustly neglected film.

It’s an unpleasant but unavoidable fact that according to the logic of capitalism, which tends to define reality exclusively in relation to marketable items, Welles as an artist died in disgrace — the butt of endless fat jokes, has-been references, and morose reflections about what would or could or should have been had the man not gone so distressingly to seed. This wasn’t, of course, the general response outside the U.S.; in Paris, to cite the other extreme, only two days after his death by heart attack on October 10, 1985, Libération came out with a twelve-page tribute. But, by and large, the American response was remorseless in its verdict. Decline, failure, inactivity, endless “taking meals” at Ma Maison in Los Angeles, and hack TV appearances by a one-time genius were mostly what one read about, often with a reference to Pauline Kael’s pejorative “Raising Kane ” thrown in for good measure.

Why was Welles hated and feared so much on his native soil? Was it because he was perceived as the man who had it all, and then threw it away? But of course Welles never had it all to begin with; despite the strength of his original RKO contract, only one of his many projects there ever got made and released to his satisfaction, and that one came dangerously close to never getting made or released at all. The legend embraced the boy wonder in power, but fell aground as soon as it had to cope with him as deposed royalty — which is what he remained for the next forty-five years. For the most part, critics and public alike remained loftily indifferent to this second Welles, at least until it was too late to make any difference: if it wasn’t another Citizen Kane, made with the virtually limitless resources of a major studio and released by a major distributor, they weren’t interested — until the film was revived as a classic a decade or so later.

Considering the brashness of Welles, it would be foolish to claim that he was entirely blameless in what happened, yet no less foolish to assume that he should somehow have tempered his brashness in order to stay in the game. (He tried that in The Stranger, and only an anti-Wellesian like James Agee could have been very pleased with the results.) And it is important to remember that he was brash as an artist, not as a celebrity or public figure; he never shocked anyone on a TV show —which is perhaps part of what made the periodic need to shock in his art so palpable. Touch of Evil, The Trial, and (as scripted) The Big Brass Ring are all like the volcanic eruptions of a caged beast kept too long in confinement — excessive at times to the point of losing control over their own meanings, yet richer and more thrilling for the headlong risks they take.

If Welles, along with Murnau, was the most poetically gifted master of camera movement in the history of cinema, this was largely because he wasn’t a rationalist like Mizoguchi or even Ophüls in his charted arabesques and flourishes, but an explorer of unconscious and semiconscious drives and transports. The bravura of the descent into and eventual ascent away from the El Rancho; the giddy, fleeting entrance into the last of the Amberson balls; the almost prenatal backward probe down a dark courtyard passageway, away from Van Stratten on his way up the stairs through the snow towards Jacob Zouk; the swoops and dives of a crane across a Mexican border town, or the serpentine chase around the pillars of a ruined building outside a strip joint — always the elation of a Victorian imagination run riot.

Significantly, at a tribute to Welles held at the Directors Guild in Hollywood last November, Charlton Heston described Welles as the most gifted director he ever worked for, but demurred when Peter Bogdanovich labeled Touch of Evil (1958), Welles’ last Hollywood film, “a masterpiece.” Heston said that he preferred to call it “the best B picture ever made.” In America, to make the best B picture ever made means, on the bottom line, to be a failure; acutely aware of this fact, even as he railed against it, Welles could not transform himself into a mainstream figure, and wound up subsidizing most of his late work himself. Quite simply, to “succeed” in the 80s, he would have to have been someone else.

Yet during the last week of his life, at age 70, he was working on at least four of his own features, and even died while typing stage directions for the last part of one of them, which he planned to shoot later the same day. And since his death, an accumulating legacy of invisible works has slowly yet obstinately been rising to the surface, giving the lie to the cherished industry fiction that all those legendary titles — Don Quixote, The Deep, The Cradle Will Rock, The Dreamers, King Lear, and still others — were merely (or mainly) apocryphal alibis from an artist who was no longer producing. The new counter-evidence, at once heartening and appalling, is that Welles’ phantom filmography really exists, and is larger than anyone expected.

Thanks to computers, economic balance sheets are available in a flash. Aesthetic balance sheets take much longer, and we are still years away from the point when the “entire” Welles legacy can simply be seen, much less studied and assessed. In the meantime, a certain amount of clarification seems both possible and desirable. Even the fragmentary evidence already becoming available suggests a different Welles from the one we have become accustomed to calling our own, and clearly this is as it should be: was there ever a film in his career that didn’t confound our expectations? And for starters, it is now evident that Welles continued to produce for half a century at very nearly the same alarming rate which he had sustained in his youth, however and whenever he could. It was only the rest of us who had slowed down.

Indeed, one could argue that it was precisely this non-stop production which aborted Welles’ career and led to so many unfinished, unrealized and/or invisible projects — to the same degree that it yielded the substantial (if partially mangled) oeuvre which we already know. Living on the wire, Welles saw life and work alike as a treacherous balancing act requiring constant improvisation, meaning that no script, however elaborate, could be simply executed, and no footage, however successful, could be simply edited — a style of work which sent chills up investors’ spines, but one not incompatible with the ordinary working methods of many painters, composers, and novelists. The resulting martyrdom has usually been rationalized in one of two ways, neatly summed up by the two Welles biographies which appeared last year: either by blaming everything on Welles (the Charles Higham formula) or by blaming fate or the world (only a slight exaggeration of Barbara Leaming’s approach). Surely the fact that Welles’ subjective private world tended to be split between fidelity and betrayal only added to this polarization. But the truth has to be somewhere in between, and no single or simple Rosebud can be produced satisfactorily to dissolve the dilemma. Perhaps it isn’t a dilemma that should be dissolved; perhaps, on the contrary, it is the peculiar strength of Welles’ work to keep it alive and worrying — a continuing rebuke and challenge to the way the world usually goes about its business.

In love with process rather than product, Welles triumphed as well as suffered by postponing deadlines; it is worth recalling that the most celebrated works of his career — Julius Caesar on stage, The War of the Worlds on radio, Citizen Kane — all thrived on last-minute delays and revisions. The only thing that changed, really, was our tolerance for such activity, and the loss is mainly ours. Welles, after all, had a thousand and one Welles films in his head and at his disposal; we only have the ones we allowed him to make.

***

In the latter part of his film career, Welles took a dramatic turn towards privacy that makes many of his late works more intimate and personal and less tied to his public image than the earlier ones. As an integral part of that life and work, the figure of Oja Kodar is likely to disconcert many of those Welles aficionados who assume that they had the master all figured out years ago. Until very recently, she has remained a willing stranger to the world of cinema, and apart from her appearance in F for Fake, unknown to most of Welles’ audience. Yet insofar as there is an invisible Orson Welles to contend with, she is clearly, along with cinematographer Gary Graver, a major collaborator, witness, and resource.

A Yugoslav sculptor who met Welles in Zagreb during the shooting of The Trial in 1962, and lived with him for the better part of the last two decades of his life, she worked on at least a dozen of his late features and projects — beginning with the dubbing of Jeanne Moreau’s lovemaking sighs in The Immortal Story and proceeding through a major part in The Deep, script collaboration and lead parts in F for Fake and The Other Side of the Wind (films whose titles are incidentally hers), work on many other scripts (including The Honorary Consul, The Surinam, A Hell of a Woman, The Big Brass Ring, and The Dreamers) and some projected or semi-realized parts (Pellegrina, the lead role in The Dreamers; Cela Brandini in The Big Brass Ring; Cordelia in Lear). Apart from this, she assumed such varying tasks as props and wardrobe on F for Fake, assistant director on The Magic Show, and everything from slate holder to focus puller on still other projects.

The Welles legacy, such as it is, consists of works in different forms and different stages of realization and completion, ranging all the way from scripts to finished films. Most of the films require lab and/or restoration work before they can be seen at all, and when this will happen depends on several factors, most of them legal and/or financial. Omitted from the inventory below, the order of which is roughly chronological (and often misleadingly so, for many projects were worked on concurrently), are several late projects or scripts about which I know little beyond their titles or subjects: adaptations of Catch-22, Conrad’s Lord Jim and Victory

(the latter of which, entitled The Surinam, Bogdanovich once planned to

produce), Greene’s The Honorary Consul (co-scripted by Kodar), Jim

Thompson’s A Hell of a Woman (co-scripted by Kodar and Gary Graver); films about Chaplin, San Simeon and Central America; and a couple of Kodar stories, Blind Window and Crazy Weather — not to mention the twenty or so earlier scripts listed in an appendix to Peter Cowie’s The Cinema of Orson Welles, as well as other titles which we may both have missed.

One further caveat. In what is conceivably the last draft of Welles’ script for The Magnificent Ambersons before shooting started, dated 7 October 1941, one encounters the following:

THE MIDDLE-AGED CITIZEN

Sixty thousand dollars for the woodwork alone! Yes, sir — hot and cold running

water upstairs and down, and stationary washstands in every last bedroom in the place!

Pretty much the same dialogue occurs in the film, but split between no less than four gawking townspeople, two men and two women. A small change, perhaps, but rhythmically and musically a crucial one in terms of the line’s delivery and impact, and only one of the countless examples of Welles’ creativity on a set. Bearing this in mind, it is impossible to read any of his unrealized scripts and confidently imagine that one can conjure up the film that would have been from the printed evidence. Yet the remarkable thing about the scripts I’ve read for The Cradle Will Rock and The Big Brass Ring — unlike the first and ninth drafts of The Dreamers, which leave more to the imagination — is that they often register like living, breathing and finished works on the page, almost as if Welles had suspected that they might never be allowed to live elsewhere. As such, they virtually cry out to be published, and one hopes eventually they will be.

IT ’S ALL TRUE.

Although much has already been written about this doomed Latin American venture of 1942, including articles by Charles Higham and Richard Wilson in this magazine, a considerable portion of the unprocessed and unedited silent footage had not until very recently been seen by anyone. In Cahiers du cinéma last autumn, Bill Krohn reported at some length on the tortuous history of this episodic documentary and

its partially recovered footage. Since then, Richard Wilson and Paramount executive Fred Chandler have been working on a documentary about It’s All True which will incorporate much of the available footage, primarily a version of the jangadeiros episode edited by Wilson, as well as interviews with some of the surviving participants on the project.

While hardly any of the three-strip Technicolor carnival sequences appears to have survived (unlike much of the black and white coverage of the same events), the most important material to have been uncovered this year is said to be the footage shot in Fortaleza with a silent Mitchell camera and a skeleton crew of four (Wilson and his wife Elizabeth, cameraman George Fanto and Welles’ secretary Shifra Haran) during Welles’s last six weeks in Brazil, which Krohn finds comparable in some respects to Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico! rushes. (Whether Welles would have appreciated the comparison is doubtful; according to Kodar, whose anticinéphilia runs as deeply as Welles’ did, my own suggestion that the beginning of Othello is Eisensteinian wouldn’t have pleased him either.)

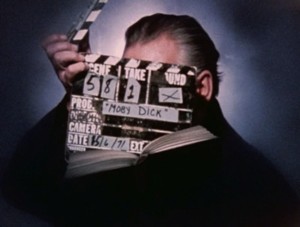

MOBY DICK.

A few sources cite a film made of Welles’ celebrated 1955 stage version of Melville’s novel, done in the form of a stage rehearsal, at London’s Hackney Empire and Scala Theatre. According to some reports, the film was never finished. Kodar has recently uncovered three very old and fragile reels of 16mm footage labeled Moby Dick; if this is in fact the material, we can perhaps look forward to a unique film record of Welles’ stage work.

LIFE OF LOLLOBRIGIDA.

In my translation of André Bazin’s second book about Welles (Elm Tree Books, 1978), I said in a footnote that this TV film was never completed. But according to Jean-Pierre Thibaudat in Libération last February, three more moldering reels comprising a half-hour personal “essay” by Welles about Lollobrigida have recently surfaced in Paris. The story recounted by Thibaudat is quintessentially Wellesian. Circa 1958, probably on his way back from Rome, Welles stopped off at one of his favorite hotels in Paris, and left the film cans behind when he departed. As the canisters bore no name or address, they wound up in the hotel’s lost property department, were never reclaimed, and were eventually transferred to another storage area, where they remained for a further two decades.

The film was made for CBS and, according to Welles in a 1982 interview, “sent to them, where there were cries of horror and disgust from [James] Aubrey there, whose nickname you remember was ‘The Smiling Cobra.’ And that was the end of that.” Apparently done in a manner that anticipates F for Fake and Filming Othello (as well as some of Fellini’s film journals), the film has Welles ruminating on other Italian stars, pinups, and Rome, speaking onscreen and off over Steinberg drawings and Italian landscapes, including brief encounters with his wife Paola Mori, and with Rosanno Brazzi and Vittorio De Sica, and finally visiting Lollobrigida in her native village (Subiaco) in the third reel, after being greeted by her three wolfhounds at the door.

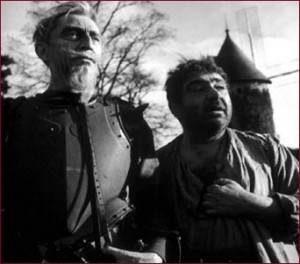

DON QUIXOTE, aka WHEN WILL YOU FINISH DON QUIXOTE?

The film with the longest production history in Welles’ career, this adaptation of Cervantes’s novel in a modern setting, financed entirely out of Welles’ own pocket, was worked on intermittently for thirty years. He started it in France in 1955, with Mischa Auer as Quixote and Akim Tamiroff as Sancho Panza, continued it in Mexico over three months in 1957 (replacing Auer with Francisco Rieguera), and added further material (shot in Mexico, Spain and Italy) in the 60s and early 70s, the last of which was footage of the Holy Week Processions in Seville, shot by Graver. He edited a more or less complete version in Rome in the mid-70s, and shortly before his death had the work print shipped to Los Angeles, planning to discard the film’s original framing device (Welles, as himself, telling the story to a young Patty McCormack) and add a color prologue and epilogue — work which was never completed.

The film is currently in the process of being restored. When it finally becomes visible, one wonders to what degree it will reflect the varying conceptions Welles had of it as he progressively developed the project. According to Bazin, the original material shot in Mexico followed “a principle of complete improvisation inspired by the early cinema.” Kodar reports that Welles, apart from supplying the narration, dubbed the voices of both Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. At one point in the early 80s, Welles hoped to return to Spain and add material about changes since the death of Franco, giving the film more of an essay form. It would appear that part of his reluctance to conclude the project stemmed from his changing attitudes towards Spain, where he lived for many years during the 50s (and which is the principal setting of The Big Brass Ring). Dominique Antoine, the French co-producer of The Other Side of the Wind, recalls that he once told her he could finish Don Quixote only if he ever decided not to go back to Spain — apparently because each return visit suggested further revisions.

(to be continued)