From The Soho News (September 8, 1981); tweaked a little on June 6, 2010. — J.R.

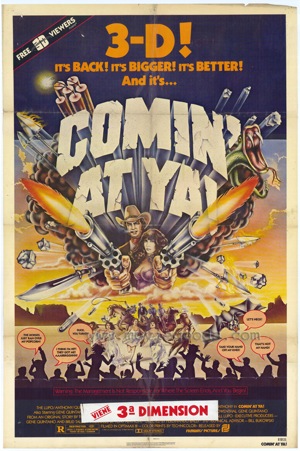

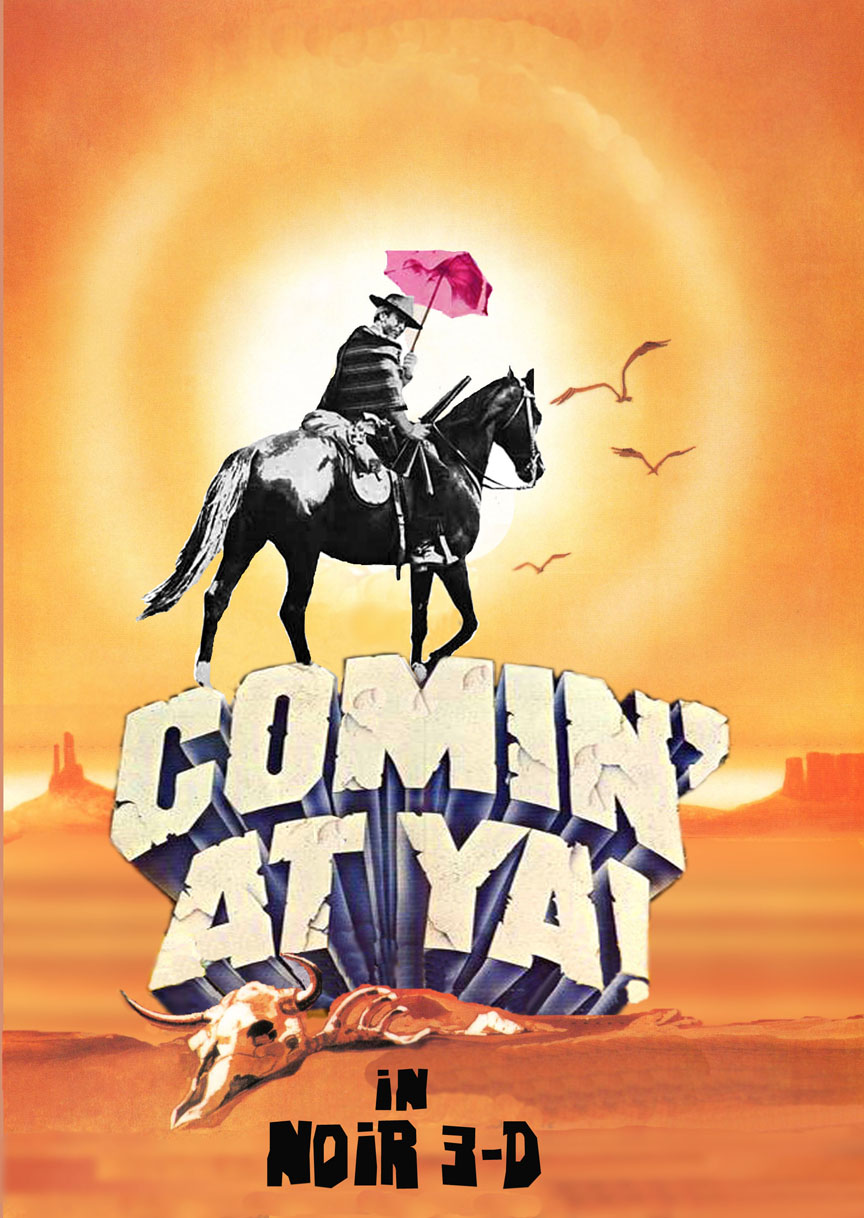

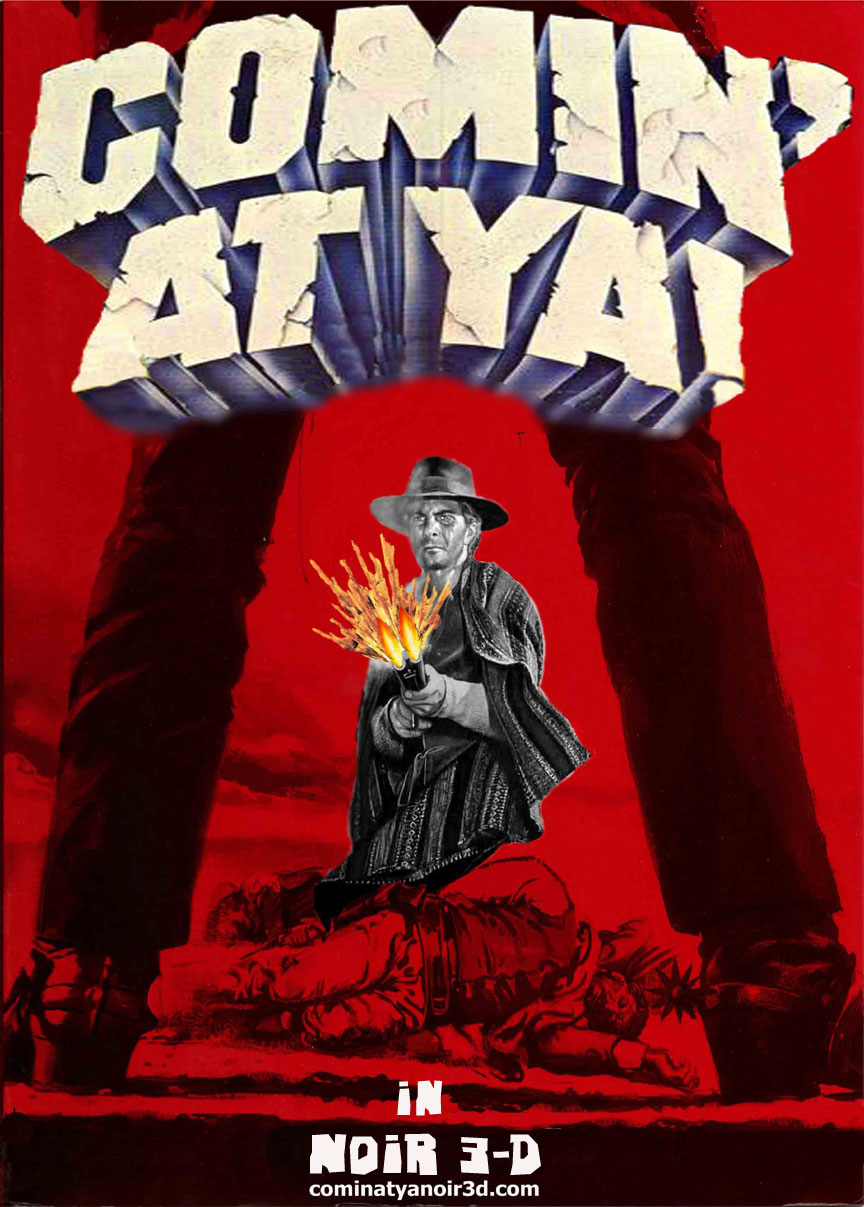

Comin’ at Ya!

Written by Lloyd Battista, Wolf Lowenthal, and Gene Quintano

Directed by Fernando Baldi

Take This Job and Shove It

Written by Jeff Bernini and Barry Schneider

Based on the song by David Allan Coe

Directed by Gus Trikonis

Let’s face facts. When notions of what a “good” movie is shrinks to the level of TV deepthink like Kramer vs. Kramer or Prince of the City, it may be time to bring the glories of the big-screen “bad” movie back again — at least if what we’re out for is fun and adventure. Unlike the most dutiful Oscar winners, whose notions of the good and proper usually revolve around the relatively straight and narrow, or the collected works of a Bergman or a Fellini that are even more consistent about their consistency — beating you into submission as they gradually meld into one all-purpose archetype — certain bad movies can boast range, unpredictability, and singularly distinctive tastes.

Indeed, a fascinating and suggestive literature has been accumulating for some time about bad movies, ranging from Jack Smith on Maria Montez to Myron Meisel on Edgar G. Ulmer, and from David Ehrenstein on Barbara Steele to J. Hoberman on “rancid glitz” in diverse manifestations. The recent formation of the Edward D. Wood, Jr. Film Appreciation Society in Los Angeles, which has already produced a marathon screening and monograph, seems a significant extension of this hallowed tradition. Having recently had some occasion myself to reflect on the “bad” movie as a discrete genre of its own — mainly in connection with programming “Buried Treasures” for the Toronto Film Festival this month, and trying to unify existentially such varied choices (all culturally rejected, ‘difficult’ mannerist transgressions) as Edward D. Wood, Jr.’s Glen or Glenda? (1953), Fritz Lang’s The Tiger of Eschnapur (1959), Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge (1963), and Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky (1976) — I’m naturally something of a sucker for Comin’ at Ya!, a real-live interesting stinker in 3-D and Cinemascope.

I’m especially partial to a bad movie that’s subversive enough to jeer at the false objectivity of critics and other movie power-brokers in its witty ads. (“Warning: The Management Is Not Responsible For Where the Screen Ends and You Begin!”) And I can’t say I entirely mind one that has the kicker of turning out to be actually “good” in some of its more salient aspects (despite a nastier and trashier side that I prefer to ignore) — for perverse and semiperverse reasons which I’ll try to enumerate:

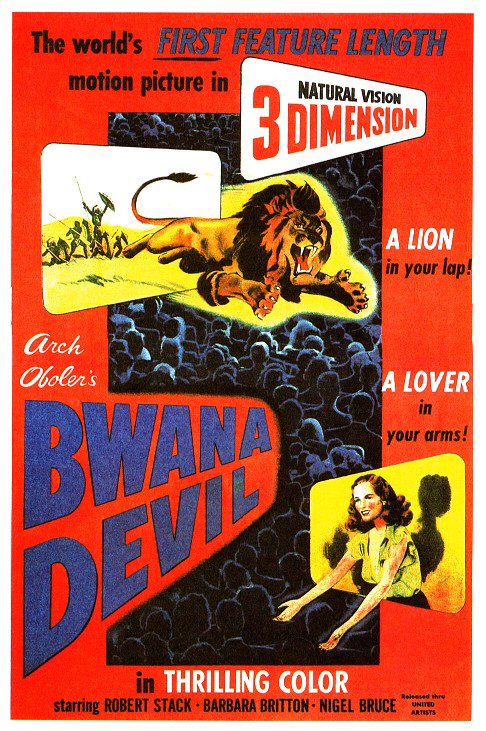

(1) Back in the ’50s, 3-D and CinemaScope developed as bitter rivals, until the latter beat the former hands down. (In terms of prestige and purchase power, there was never any real contest; Bwana Devil advertised a lion in your lap, but The Robe offered a much pricier taste of Jesus and a spiritual lump in your throat.) Comin’ at Ya! is a campy spaghetti Western that not only combines these complementary processes, but also integrally composes in them. Director Ferdinando Baldi’s multilayered use of depth and wide-screen breadth becomes the movie’s subject, as its title succinctly indicates — articulated on a shot-by-shot basis. Viscerally speaking, it often aims for the same sort of murky, cluttered Sternbergian depth that Wadleigh’s Wolfen partially achieves through the ears. And it often succeeds.

(2) At the same time that one can say that Comin’ at Ya! is composed in relation to the parameters of 3-D and Scope, one can also consider it decomposed, in relation to being a mindless copycat ripoff of a Sergio Leone /Ennio Morricone revenge extravaganza like Once Upon a Time In the West. There’s the same dreamy, wordless soprano waxing obligatory gore and mechanical revenge cruelty, the same mannered emphasis on pregnant pauses as deadly dudes stand around idiotically with their yoyos or harmonicas awaiting villent, grandstanding confrontations. The actors move like automatons in rituals that are so formalized and devoid of thought and feeling that no one — least of all characters or spectators — is supposed to be very concerned about why these things are occurring, at least in terms of narrative logic. Bats and rats emerge separately from the woodwork and torment characters at length, not for any plot reasons, but simply to keep an overall pattern of harassment going.

(3) Best of all, the visual composition and narration decomposition suggested above work together hand in glove. Every link in the narrative chain is reduced (and reducible) to a fancy 3-D effect that wields aggression against the spectator, while conversely, what the 3-D ultimately does is expose every creaking bone in the genre’s skeletal structure of events by literally stretching each one out, temporally as well as spatially. The time and space needed in order to register a 3-D assault thus becomes the movie’s principal form of rhythmic accent and stylistic inflection, and the resulting narrative slowdown — often accompanied by literal slow-motion, converting the actors into sleepwalkers — assumes a musical function, turning the title 3-D effects into cadenzas or arias arising irrelevantly out of the dumb cliché plot. The result may be one of the goofiest pieces of narrative disassociation available this side of Marguerite Duras.

(4) The 3-D effects, moreover, are so steady and plentiful that they comprise a kind of catalogue of spectator abuse — much as the plot comprises a catalogue of character abuse. (Take away the abuse and effects and what’s left disintegrates into a fine powder.) In the wonderfully cornball credits sequence, practically every name and function is cutely and incongruously attached to some object in a barn that gets poked in your face — a wine bottle, a snake, a spill of beans, a coffee pot — and before long, in the story proper, a basket of fruit, a fistful of gold coins, rats, bats, ropes, sabers, spears, hands, guns of all sizes, arrows (flaming and otherwise), shucked corn, peeled potato, a yoyo, a rubber ball, lots of darts, a hatchet, a lethal board, a whip’s lash, and God knows what else are all dumped, dropped, splattered, or thrown straight into your lap. The endless procession of Biblical devastations is later reprised at the end — almost like a curtain call, or one of those rapidly edited flashback summaries associated with middle-period Godard — to emphasize its independence from narrative logic even further.

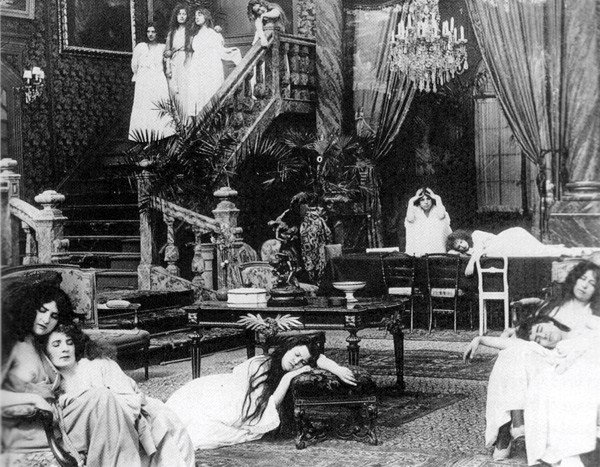

(5) Perhaps the most curious aspect of the film’s ultimately monotonous anthology of violent aggression is how successfully it seems to resist most signs of human or dramatic motivation — often reduced to the purity of the sheer tawdry effect, indulged in simply for its sown sake. An Indian with a spear in his belly totters in closeup for what feels like an eternity (an effect reprised at the end), to dramatize not a personal death but a long spear end comin’ at ya. In one of the shoot-outs, one varmint gets explicitly blasted in the balls by a rifle — as if to clarify an overall approach to camera placement that aims (and presumably locates) a surprising amount of the movie in the spectator’s genital area (giving the movie-s title an extra shade of sexual meaning). Needless to say, this being an Italian Western, a lot of the violence is directed against women — most of whom are shanghaied white-slave items, garbed in white and collectively draped around elaborate interiors, like the mad ladies in Feuillade’s Tih Minh. To be sure, though, one fat male actor (whom 3-D makes even fatter) gets nibbled on by rats for what seems to be hours.

(6) When these rats are finally pulled off him, they’re naturally flung out at us, one by one — following a share-and-share alike principle between characters and spectators that places them/us in the virtually identical slot of the passive Hitchcockian stooge, masochistic little things meant to be harassed. I know that Sir Alfred’s Dial M for Murder is supposed to be the acme of 3-D mise en scène, but for layered compositions in depth, angled for maximum effect, Comin’ at Ya! is a lot more striking, in more ways than one. (The trouble with Hitchcock’s cautious use of the process is that it rules out the sort of grand treatment of 3-D that a Vertigo would have demanded.) At the very least, it’s the best semi-hilarious bad movie I’ve seen all week, shucking corn in the general direction of your privates with the brightest of them.

***

The second best (i.e., the worst), vaguely based on a hit song performed by Johnny Paycheck and mainly set in and around a beer factory in Dubuque, Iowa, is Take This Job and Shove It. What makes this loose, semi-incoherent movie bad in a technical sense, yet without any redeeming aesthetic implications, is it utter lack of any dogged focus or design in its overall spiritual makeup. Relaxation is one thing, but laid-back indecisiveness can be a little hard to take.

Robert Hays, who played the romantic lead in Airplane! — a pretty-boy Belmondo minus the latter’s pug nose and boorish manner — plays a junior executive in a Midwestern conglomerate sent back to his home town (Dubuque) by his boorish boss (Eddie Albert, once again in a cocky nautical cap) to improve the efficiency of a brewery there. I theory, the callow, smugly naive hero eventually learns how to warn to his employees and vice versa, but what we actually hear and see turns out to be so patchy and incomplete — whether due to omissions at the script ot editing level is not clear — that we have to accept this concept, if at all, strictly on faith.

Similarly taken for granted is the flat-footed visual style (every shot a cliché) and editing rhythm (pretty lumpy throughout), although I suppose a few dregs of some primitive well-meaning political ideas about workers’ rights are still discernible between the joints of this rickety effort. If only the movie showed a little more confidence or enthusiasm about any of what it was doing — if, for instance, it used or handled raunchiness without giving the impression of learning it through a correspondence course, or establishing an improbable (if seemingly first-rate) Nashville nightclub in the middle of Iowa — one might give it some points for trying.

Unfortunately, the movie flounders from one conceit or reflex to another without ever convincing one that any continuous vision is at stake. Apart from a couple of good country songs and a nicely nuanced performance from David Keith as a good old boy, Take That Job and Shove It has little of the decisiveness telegraphed in the title and closing moments; most of the rest is just drift. Under the circumstances, such actors as Art Carney, Barbara Hershey, Penelope Milford, Martin Mull, and Tim Thomerson perform capably but forgettably.