From the Chicago Reader (February 21, 2008). I believe this was my last long review before I left my staff job there. — J.R.

CHARLIE BARTLETT ***

Directed by Jon Poll

I just rewatched Allan Moyle’s Pump Up the Volume, a radical and rebellious teen movie I gave four stars in 1990. I think it holds up, and apparently I’m not the only one: the average rating of the 62 customer reviews it has on Amazon.com is four and a half out of five stars.

The new rebellious teen movie Charlie Bartlett isn’t as good or as radical; it’s more an edgy comedy than a rabble-rouser. But it reminded me of Pump Up the Volume in many ways: it’s one of the first features for a middle-aged director; it captures teenage despair leading up to a suicide attempt (successful in Pump Up the Volume, unsuccessful here); one of its lead characters has a school administrator as a father (the hero in Pump Up the Volume, the heroine here); and it depicts a general disgruntlement about the way schools are run, culminating in a student uprising. The movies are even comparably derivative of others: Pump Up the Volume plundered some of its best ideas from Rebel Without a Cause, Citizens Band, Network, and Talk Radio, while Charlie Bartlett seems especially indebted to Mumford, all the way down to its final blackout gag.

Charlie Bartlett might not be as bold as its predecessor. Yet given how politically gutless most teen movies have become, it may provoke audiences as much as Moyle’s movie did 18 years ago. I’ve lost count of the number of times its opening has been delayed since I first saw it last July, so clearly it has somebody worried that its defiant spirit will cut into its profitability — which is entirely to its credit.

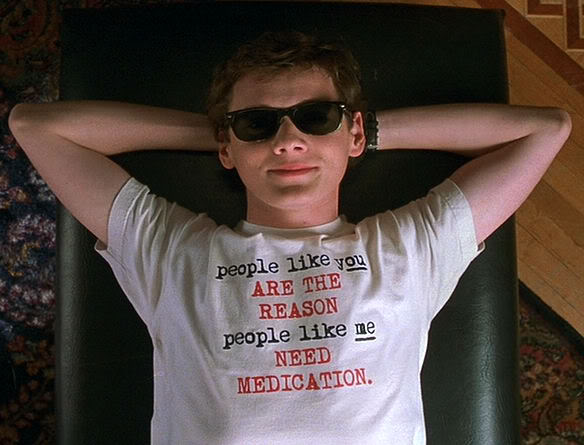

The satirical plot flaunts taboos about social class, psychiatry, and drugs. The title hero (Anton Yelchin) lives in a mansion, gets chauffeured around in a limo, and finds ways to get thrown out of a series of prep schools. After he gets expelled from the last one for counterfeiting driver’s licenses, his tolerant, doting mother (Hope Davis) is unable to bribe his way back in, and he’s reduced to enrolling at the local public school.

His preppy blazer quickly gets him into trouble there. A bully named Murphy (Tyler Hilton) regularly beats him up, stuffs his head into a toilet, and even gets another kid to document the violence on video. The only solution Charlie’s mom can think of is to send him to his uncle, a psychiatrist who immediately surmises that he has ADD and prescribes Ritalin.

Charlie then solves his bully problem by inviting Murphy to become his business partner in selling Ritalin to their classmates. Eventually the operation expands: from his uncle Charlie acquires a veritable pharmacy of drugs that Murphy turns around and sells, and they start hawking old videos of Murphy beating other kids up, with a cut of the proceeds going to the victims. Meanwhile, Charlie sets up a combination confessional and psychiatry practice in a stall in the boys’ bathroom, quizzing classmates (male and female) in adjacent stalls and coming up with pharmaceutical solutions to their ailments. He thereby becomes the most popular boy in the school, acquiring the status of a rock star — or evangelist — and fulfilling his most treasured fantasy of empowerment.

A silly premise? You bet. But arguably not as silly as some of the social attitudes it ridicules, such as the widespread assumptions that class barriers are easy to overcome (see The Bucket List), that schools must have surveillance cameras (another big issue here), and that students should be medicated for maladies and forms of depression that didn’t exist for previous generations. (As psychiatrist and author Peter D. Kramer writes in a recent issue of the New York Review of Books, “Psychiatric diagnosis [has] been subject to a sort of ‘diagnostic bracket creep’ — the expansion of categories to match the scope of relevant medications.”)

And what about the tolerance for booze in the U.S. compared with the hysterical demonizing of marijuana? One of the funniest jokes in Charlie Bartlett is in a simple act of casting: the high school principal, the single father of Charlie’s girlfriend (Kat Dennings), is an alcoholic played by former drug abuser Robert Downey Jr. He’s granted a comic vulnerability that makes him more than a one-dimensional dyed-in-the-wool villain — one of the few instances where the characterization in Charlie Bartlett is more nuanced than in Pump Up the Volume. At one point he installs surveillance cameras in the student lounge, sparking violent protests. Yet during one of his binges, he uses a remote control to operate a motorized toy boat in his swimming pool while firing idly at it with a handgun. The sheer pathos of his despair is touching, clarifying to what extent he’s just an older version of Charlie Bartlett. By contrast, the principal in Pump Up the Volume — played by jazz singer Annie Ross, another bit of joke casting — is never granted any affection.

Less successfully handled is a gratuitous subplot about Charlie’s missing father. The fact that this unseen character is in prison and that Charlie hasn’t forgiven him is never developed, and the belated revelation of his crime — which only begs the question of what the source of the Bartlett fortune is — seems even more pointless.

Antiauthoritarian gestures are of course standard fare in teen movies. The underlying premise of the rock movies of the 50s was that music was the main form of rebellion available. As its title suggests, Pump Up the Volume doesn’t so much negate that idea as build on it through the free-form talk-radio tirades of an anonymous pirate broadcaster (Christian Slater) who intersperses his rants with favorite cuts. But in Charlie Bartlett, even though some live music figures in a celebratory party thrown by Charlie, the theme of music as rebellion is barely present. (At one point, however, high on Ritalin, he parodies an older brand of pop music by pounding away on a piano and singing.) The antiauthoritarian gestures in this movie still have something to do with sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. But they’re also caught up in the parents’ sickness — at times they feel closer to desperate sarcasm or capitalist revenge than to the earlier attempts at liberation.