From The Guardian (August 31, 2002). Having more recently attended a 35-millimeter screening of Greed (not the longer version put together by Rick Schmidlin) at the St. Louis Humanities Festival, on April 6, 2013, I was delighted to see all 240 seats in the auditorium filled (another twenty were turned away); most of the audience remained and were clearly enrapt, and the majority stuck around for an hour-long discussion afterwards.

Thanks to the very generous help of a reader, Abe Slaney, in clearing up the format problems in this post, I’m reposting it. — J.R.

Legends about the ‘complete’ Greed have existed ever since Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer reduced Erich von Stroheim’s footage to ten reels and released the results in 1924. What they released, containing the only surviving footage, is scheduled to be shown twice in the National Film Theatre’s Stroheim retrospective.

Rick Schmidlin’s four-hour reconstruction on video of what the film might have been, also showing twice at the NFT, should be regarded as a study version. It suggests what some of the longer versions of Greed might have been like, though it isn’t in any way a replica of any of those versions. Schmidlin’s main sources, apart from the ten-reel version and a new score, are Stroheim’s ‘continuity screenplay,’ dated March 31, 1923, and hundreds of rephotographed stills of missing scenes — sometimes with added pans and zooms, sometimes cropped, often with opening and closing irises.

It’s a useful and enlightening undertaking that should alter and enhance most people’s understanding of Greed. But unlike the recent reconstruction of the original Metropolis, which fills out the missing pieces of a single original cut with explanatory intertitles, this can’t be confused with even the provisional completion of a work that, by necessity, is doomed to remain unfinished.

On the other hand, if you believe the original hype from Turner Classic Movies, what’s been lost has now been found — even though the studio burned the footage it deleted over 75 years ago. According to Stroheim, this was done in order to extract the few cents’ worth of silver contained in the nitrate.

In the interests of full disclosure: I was hired by Schmidlin a few years ago as a consultant on another speculative version of a classic, Touch of Evil — based in that case on a lengthy memo that Orson Welles wrote to Universal Pictures about suggested changes in their rough cut. (This memo is now available on the DVD of that version — unfortunately, the only one readily available) [2013: The complete memo is now available both online and in a three-disc DVD box set]. Schmidlin also invited me to serve as consultant on his Greed project, but I regretfully declined because he couldn’t afford to pay me a fee, suggesting that he hire Stroheim biographer Richard Koszarski in my stead. (My employment at Universal had already verged on charity work, and it seemed demoralizing to perform comparable services for Turner Classic Movies for no fee at all.)

To give a rough breakdown of all the things that ‘the complete Greed‘ might stand for: 446 reels were shot in 1923. In early 1924 Stroheim apparently screened various rough cuts to friends that were about a tenth as long, ranging from 47 to 42 reels. Considering all the things that can transpire at private screenings — projector breakdowns, pauses for meals or reel changes — it’s impossible to gauge how long these showings took, but most accounts suggest between eight and ten hours. The next version Stroheim edited, said to be somewhere between 28 and 22 reels, still ran over four hours. When he asked editor Grant Whytock to try his hand at producing a still shorter cut — one designed to be shown over two evenings that eliminated one of the story’s two major subplots — the results were somewhere between 15 and 18 reels. But this too was rejected by M-G-M, who whittled the film down to ten, meanwhile adding various intertitles to account for some of the gaps.

Both before and after Greed, most of Stroheim’s released films turned a profit — which helps to explain why he survived as long as he did in Hollywood, despite constant battles and cost overruns with the studios. Whether any of his own cuts of Greed could have been profitable is hard to say, but it’s difficult to fathom how Hollywood apologists can argue that Irving Thalberg was justified in eviscerating Greed for business reasons, because the movie he released made back less than half its budget.

It’s a truism that writers are among the most neglected creative participants in movies, especially in relation to actors and directors. Yet a special kind of hell awaits writer-director-performers when they function as writers, especially if their names happen to be Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, John Cassavetes, or Erich von Stroheim. All four were mavericks who had shifting and sometimes troubled relationships to the Hollywood mainstream, confused all the more by their mythical status. They generally register in the public mind first as actors, then as directors, and finally as writers, if at all, only in the most confused and uncertain manner.

Welles had to contend with critics who challenged his capacities and credentials as a writer (above all, Pauline Kael in the case of Citizen Kane) while Cassavetes, who was wrongly believed to have substituted improvisation for writing in most of his own features, was rarely considered as a writer at all. The power of Chaplin’s image made him viewed as an actor first and last, an old-fashioned director sometimes, and a writer only occasionally. With Stroheim, his authoritarian image as director and as actor left generally little room for any notion of him as a writer. Yet it’s mainly as a writer that we can come to any understanding of what he was trying to accomplish in his films — above all in Greed, where his only appearance as an actor is a cameo as a balloon seller, missing from the release version.

The version of Stroheim’s screenplay for Greed edited by Joel W. Finler and published by Lorrimer in 1972 is an earlier and somewhat longer adaptation of Frank Norris’s 1899 novel McTeague than the one used by Schmidlin, but it still gives one a pretty good idea of the writer-director’s intentions. Contrary to the absurd legend that Stroheim simply ‘filmed’ Norris page by page, nearly a fifth of the plot in this script transpires before the first sentence of the novel, and much of what follows brilliantly expands or elaborates upon the original.

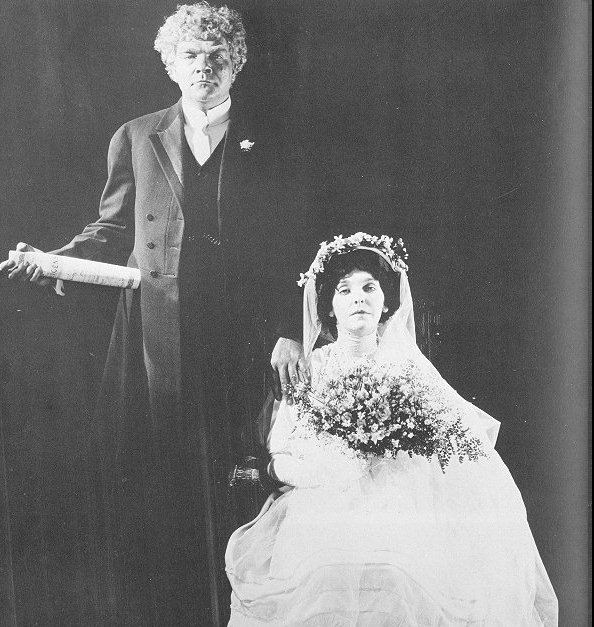

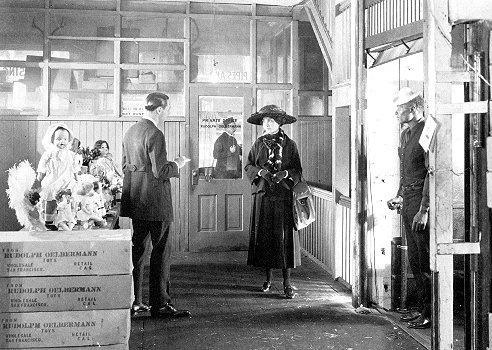

To summarize the plot in a couple of breathless sentences, it shows how two devoted best friends in San Francisco, Mac McTeague (Gibson Gowland) and Marcus Schouler (Jean Hersholt), and Marcus’s cousin in Oakland, Trina Sieppe (Zasu Pitts), who marries McTeague, wind up destroying one another after she wins $5,000 in a lottery. Trina gradually loses her mind, Mac loses his job as a dentist, both see most of their kindness and gentility progressively stripped away, and Marcus betrays both of them out of envy.

As an act and as a statement, the story clearly got under the skin of the MGM studio heads. For Greed has got to be the most negative depiction of what money can do to people that exists in movies — though curiously, it has never been taken up as a cause by Marxist critics, at least not for ostensibly Marxist reasons.

Part of the story’s greatness in both the novel and Stroheim’s adaptation is the degree to which it makes the deterioration of all three characters terrifying real and believable. And some of the worst damage done by MGM’s reduction was to make this process seem forced and abrupt rather than a logical development of these working-class characters, all of whom are treated as sympathetic as well as horrifying at separate junctures in the story. Marcus remains a relatively coarse figure throughout, but Mac and Trina are remarkably multifaceted and three-dimensional. This is even more the case in Stroheim’s movie than in Norris’s novel, thanks to the remarkable performances of Gowland and Pitts, who succeed so well in embodying these figures that they seem to exist between the shots and sequences as well as during them.

Schmidlin’s version makes these two much more solid. The stills and additional dialogue expand their essences, and four other characters comprising two couples (three of them missing from the release version) provide musical rhymes and stylistic and thematic contrasts that help define Mac and Trina. One couple is more genteel: Old Grannis and Miss Baker, shy, elderly neighbors of Mac and Marcus who each secretly nurture romantic longings for the other. (The images of their eventual conjugal bliss are rendered in full color — one of the most striking effects in this version, though, like every other glimpse we have of these characters, it’s conveyed only through stills.)

The other couple is more brutal: Maria Macapa (Dale Fuller), who appears briefly in the release version, and Zerkow — a grotesque junk dealer whom Norris designated as Jewish, though Stroheim pointedly omitted this detail. Their grim relationship is driven by greed and mutual mistrust and mainly lighted and framed in an expressionist manner, in contrast to the poetic styling of Old Grannis and Miss Baker, which shows the influence of D.W. Griffith.

Norris used these supplementary characters, representing Mac and Trina’s higher instincts and baser impulses, the way a painter might use colors, to enhance and echo his main subjects.

Stroheim adheres to the same basic principles, yet through the powers of his imagination he makes even more out of them. Indeed, another reason why Greed is even better than McTeague is that Stroheim had more lived experience to bring to the material. Norris was a millionaire’s son and a gifted slummer, Stroheim the son of a Jewish Viennese merchant who arrived penniless in America at 24 and then eventually persuaded practically everyone in Hollywood and western Europe up until his death that he had links to the Austrian aristocracy.

The formidable antihero he plays in Foolish Wives — a film that’s as great, as complex, and as accomplished as Greed, though less than a third of it survives today — is an imposter, counterfeiter, and scam artist in Monte Carlo.

Part of the fascination of Stroheim’s cinema remains its autobiographical aspects — even when, as in this case, he appears to be hiding in plain sight.

An earlier version of this character and performance crops up in Stroheim’s first feature, the 1919 Blind Husbands —the only one of his films, alas, that survives in a version approximating its original form. All the others were shortened, recut, edited by others (as in Queen Kelly, after the shooting was halted in mid-production), and/or partially reshot. Even parts of what remained of some films have subsequently been lost — such as the second part of The Wedding March, lost in a fire at the Cinémathèque Française. (The late Henri Langlois once claimed that Stroheim’s ghost — unhappy with all the changes made in the film — was responsible.)

On another level, Greed isn’t merely a novelistic account of what happens to certain people but a history of the vicissitudes of certain objects — which becomes much clearer in Schmidlin’s version. Anticipating all the things that Edward Yang would do with a flashlight and a samurai sword over the course of his Taiwanese epic A Brighter Summer Day (1991), the progress and fate of Mac and Trina’s wedding photograph — one torn half of which is ultimately used to make a wanted poster for Mac after he murders Trina — becomes a disquieting condensation of the entire story.

Given the mixture of visual styles — and the dabs of gold added to appropriate objects in Schmidlin’s version, following indications in the continuity screenplay, and symbolic inserts of abnormally long, bony hands fingering gold coins — it simply won’t do to call Greed a triumph of realism, as many have. Clearly some of it is and some of it isn’t.

One thing that isn’t realistic is the ambiguous and multilayered time frame. Stroheim updated Norris’s plot, though not always consistently, from the end of the 19th century to 1908 and afterward, corresponding to the period of his own first years in America. As a result, sometimes the major characters are dressed in the clothes of the 1890s (fidelity to Norris), the extras in crowd scenes are dressed in the clothes of 1923 (fidelity to the present, when the film was shot), and the stated time of the action falls roughly in between these period (fidelity to Stroheim’s autobiographical impulses).

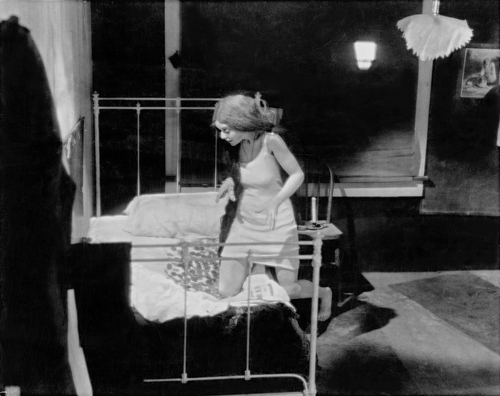

A similar paradox can be seen in some of the camera placements, which alternately suggest theatrical space and realistic locations. The most obvious instance of this is the long shot of Mac closing a curtain that separates us from him and Trina as the two of them prepare for bed on their wedding night. Another example is strictly anecdotal rather than something found in the film itself. Kevin Brownlow once showed me an unpublished interview he conducted with one of the film’s two cinematographers, William H. Daniels. According to Daniels, Stroheim’s passion for cramming naturalistic details into shots and his refusal to budge once particular camera setups had been decided upon sometimes led him to have walls torn down in his ‘natural’ locations in order to get the camera into the desired position.

Working on the reconfigured Touch of Evil, I discovered that one couldn’t delete or alter any single shot without affecting everything else, sometimes in subtle and mysterious ways. The same thing has to be true of Greed, and one of the most pronounced pleasures I had in watching Schmidlin’s version was seeing much of the older footage as if for the first time. Again and again I found myself asking of a particular scene, ‘Did I really see this before?’ In every case I had — there’s no new footage apart from the stills and additional dialogue in intertitles — but the extra dialogue often has the effect of giving the old footage a fresh appearance.

Yet with some entire dramatic scenes reduced to a few stills, you can’t indicate what a six- or eight-hour movie might have been like. I especially regret the nearly complete absence here of a long, early sequence covering about 30 pages in the Lorrimer script that recounts what most of the major characters do on a ‘typical’ Saturday — the day that precedes the novel’s opening, as it happens — before most of them have even met one another and before we’re sure what most of them have to do with the main story. This stretch, which borders on meditative nonnarrative, would undoubtedly still seem radical today. Coming across like an endless series of digressions, it foregrounds Stroheim’s manner of accumulating details while suspending narrative in the usual sense. This sequence might have been what one writer who saw the 45-reel Greed had in mind when he compared it to Les miserables and added, ‘Episodes come along that you think have no bearing on the story, then 12 or 14 reels later, it hits you with a crash.’

Greed will always be unfinished and incomplete, just as Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons will always remain that way. Contrary to rumor and studio propaganda, capitalism doesn’t always have a happy ending. But Schmidlin’s work can allow us to use our imaginations to construct what might have been. This is an inconclusive activity but also an exciting prospect — because it requires our creativity and not simply our desire to take in a great movie and then be done with it. A perpetually unfinished masterpiece throws the ball into our court, which is right where it belongs.

Published on 10 Apr 2013 in Notes, by jrosenbaum