This was apparently written in 2002, but I can no longer recall the circumstances or occasion for my writing it. — J.R.

During my only visit so far to Iran — as a member of the jury of the Fajr film festival in Tehran last year —- I was asked the same question repeatedly by many of the Iranians I met: “Why do you Americans [or westerners] like Iranian films so much?” And more often than not, this was followed by a second question: “Is it because they show so many poor people, which is the image of Iran that Americans [or westerners] prefer to have?” Given that many of the most valued and validated Iranian art films shown abroad are either banned or ignored on their home turf, it seemed like an understandable source of curiosity, made even more striking by the oft-reported fact that the films seen most often by most Iranians are unsubtitled, pirated videos of brand new American commercial features.

With these circumstances in mind, my usual response to their question was something like, “It’s true that Iranian art movies tend to show too many poor people. But American commercial movies tend to show too many rich people, and if you think they provide an accurate picture of the way we live, then you’re just as mistaken as we are.” And I couldn’t help but reflect further that part of what has made Iran a movie-mad country in recent years, with about a dozen film magazines coming out regularly, is that cinema provides one of the only routes to upward class mobility available in that society. The Chicago-based Iranian critic and filmmaker Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, with whom I recently collaborated on a forthcoming book about Kiarostami, has compared the current appeal of filmmaking in Iran to the appeal of basketball to black ghetto youth in the U.S. Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s status as a local culture hero —- an impoverished fundamentalist who evolved into a successful reformist filmmaker — is undoubtedly tied to this fact, and the desire of an out-of-work bookbinder to impersonate someone like him, giving him access to upper-class society, which set the real-life plot of Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-up in motion, clearly has a lot to do with what made that 1990 film the most influential of all Iranian new wave features.

A central fact of Tehran’s class structure seems relevant here: most of the relatively well-to-do Iranians, including Kiarostami, live on the side of a prominent mountain in the northern part of the city; Makhmalbaf, who by now is fairly well-to-do himself, does not, and prefers to keep his school and production company, the Makhmalbaf Film House, down below. Both Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf are filmmakers with social consciences whose recent works often gravitate around questions concerning how privileged people relate to the poor and vice versa, but it seems significant that Makhmalbaf prefers to live in a more middle-class section of Tehran. This may also help to focus certain debates within Iranian film culture about the legitimacy of certain art films focusing on poor people —- an issue that affects the readings of certain films by Abolfazl Jalili, for instance, in relation to their ethnographic tendencies.

Perhaps even more relevant to contemporary Iranian society are the facts that 65% of the population is under the age of 21 and that voting ages there are younger than in most other parts of the world —- information that seems especially relevant to Secret Ballot. This more generally suggests, in conjunction with Mahkmalbaf’s example, that the desire to bridge fundamentalist and reformist elements in the population, corresponding in many respects to the orientations of separate generations, is as important as the desire to bridge class differences. (Under the Moonlight, to cite one example, seems a direct reflection of this issue.) Thus one is faced with the paradox that, in spite of the heavily restricted freedoms of Iranian women, the most famous teenage filmmaker in the world only a few years ago was Makhmalbaf’s daughter Samira, when she made her first feature, The Apple. (A comparable paradox can be seen in the exalted status in 20th century Persian literature of the controversial late feminist poet Forugh Farrokhzad —- whose only film, a 1962 short about a leper colony entitled The House is Black, could arguably be called an early harbinger of the Iranian new wave.)

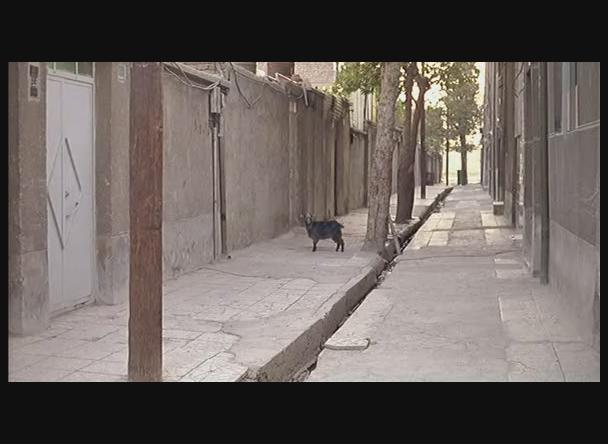

Social facts of this kind have a crucial bearing on many of the aesthetic traits of the new Iranian cinema. The widespread tendency in Iranian art films to shoot mainly or exclusively in exteriors can be traced in part to the censorship policies making it forbidden to show women in domestic interiors without their chadors, despite the fact that Iranian women almost invariably remove their chadors when they’re at home. But this practice of shooting outdoors has interesting social consequences as well, so that one could discuss the use of cars in Kiarostami as emblems of the middle and upper classes being inflected socially as well as aesthetically in terms of whether their windows are open or closed. Closed windows create a sense of private space for the driver and open windows invite exchanges with pedestrians, much as moviegoing (as opposed to video watching) generally entails a private experience within a public space. All of which suggests part of what seems to connect cinema itself with social mobility in Iranian society.

Published on 13 Aug 2011 in Notes, by jrosenbaum