From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1989). — J.R.

Alain Resnais’ comeback in 1974 after five years’ absence (precipitated by the commercial failure of Je t’aime, je t’aime), and like many other of his films, it has improved with age. Scripted by Jorge Semprun (La guerre est finie, Z), it tells the true story of a notorious international financier (Jean-Paul Belmondo) whose ruin in 1933 led to a major political scandal and his own death. While the script isn’t always lucid — some attempts to counterpoint Stavisky’s destiny with that of Leon Trotsky, given political asylum in France during the time of the events covered, appear a bit forced — the power of Resnais’ evocative editing is as strong as ever. Using a gorgeous original score by Stephen Sondheim, elegant sets and locations, and beautiful color cinematography by Sacha Vierny, Resnais models his liquid, bittersweet style on Lubitsch, and the shimmering, romantic results are often spellbinding and haunting. With Anny Duperey, Charles Boyer (in what may be his last great screen performance), Michel Lonsdale, Francois Perier, Claude Rich, and, in an early cameo, Gerard Depardieu. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 25, 1991). — J.R.

LITTLE MAN TATE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jodie Foster

Written by Scott Frank

With Adam Hann-Byrd, Jodie Foster, Dianne Wiest, Harry Connick Jr., David Pierce, Debi Mazar, and P.J. Ochlan.

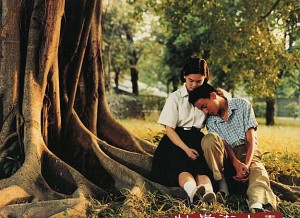

Part of what’s refreshing about Jodie Foster’s first feature as a director is its quirky style and vision; even the picture’s limitations have a certain offbeat integrity. In 90 percent of the movies we see the flaws are the same old flaws endlessly recycled (inherited like family curses, passed along like viruses): sentimentality, cliched characters and behavior, and stock attitudes, camera placements, and audience manipulations. Relatively free of these familiar blemishes, Little Man Tate winds up with a few of its own — “missing pieces” might be more accurate — but most of these problems seem to have been arrived at honestly rather than automatically imported from other movies.

The title hero is a boy genius named Fred (Adam Hann-Byrd) who occasionally narrates his own story, which transpires mainly between his seventh and eighth birthdays. He’s gifted in so many ways that, at least on the schematic level of Scott Frank’s script, he often seems like several boy geniuses jammed together: a self-taught reader by age one, he also quickly reveals himself to be a talented visual artist, a remarkable classical pianist, an original and accomplished poet, and a mathematical wizard who breezes through a college course in quantum physics when he’s seven. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 510). — J.R.

Mes Petites Amoureuses

France, 1975

Director: Jean Eustache

Southwest France, circa 1950. Daniel, a schoolboy living with his grandmother, recalls hitting a schoolmate gratuitously, and getting his first erection as a candle-bearer during Mass. Impressed by a sword-swallower in a circus who lies down on broken glass, he duplicates this feat with artifice and fake blood to impress his friends, but later is overcome by a local girl who forces him to the ground and sits on hirn. After he has passed his entrance exams, his mother arrives on a visit with her lover José, a Spanish labourer. Eventually he moves to the city to join his mother and José, but the former forbids him to attend school and has him work without pay as an apprentice to Henri, José’s brother, at a bike repair shop. Spending much of his time looking at women, he goes to see Pandora and the Flying Dutchman at a local cinema where, imitating another boy in the audience, he kisses and caresses a girl seated in front of him, but then leaves the film before it is over. He frequents the local Bar des Quatre Fontaines, where he observes his more amorously active friends, and also attends a local fair where he feels the leg of a girl in the crowd while they listen to the singing of other girls from the nearby convent of St. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 7, 1995). — J.R.

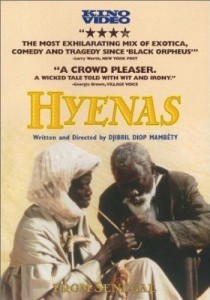

Hyenas

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Djibril Diop Mambety, adapted from Friedrich Durrenmatt’s The Visit

With Mansour Diouf, Ami Diakhate, Mahouredia Gueye, Issa Ramagelissa Samb, Kaoru Egushi, and Mambety.

“The plot by now must be well known; a flamboyant, much-married millionairess returns to the Middle-European town where she was born and offers the inhabitants a free gift of a billion marks if they will consent to murder the man who, many years ago, seduced and jilted her….Eventually, and chillingly, her chosen victim is slaughtered, but I quarrel with those who see the play merely as a satire on greed. It is really a satire on bourgeois democracy. The citizens…vote to decide whether the hero shall live or die, and he agrees to abide by their decision. Swayed by the dangled promise of prosperity, they pronounce him guilty. The verdict is at once monstrously unjust and entirely democratic. When the curtain falls, the question that Herr Dürrenmatt intends to leave in our minds is this: at what point does economic necessity turn democracy into a hoax?”

These words of wisdom from Kenneth Tynan, written in 1960 about Friedrich Durrenmatt’s 1956 play The Visit, are well worth recalling when you make your way to the Film Center this week or next to see Djibril Diop Mambety’s wonderful Senegalese feature Hyenas (1992) at the Black Harvest International Film and Video Festival. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 16, 1995). — J.R.

The Glass Shield

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Charles Burnett

With Michael Boatman, Lori Petty, Ice Cube, Elliott Gould, Richard Anderson, Don Harvey, Michael Ironside, Michael Gregory, Bernie Casey, and M. Emmet Walsh.

Smoke

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Wayne Wang

Written by Paul Auster

With William Hurt, Harvey Keitel, Stockard Channing, Harold Perrineau, Giancarlo Esposito, Ashley Judd, and Forest Whitaker.

My dozen favorite films at Cannes this year? Terence Davies’s ecstatic wide-screen The Neon Bible, set in a perfectly imagined Georgia of the early 40s, with Gena Rowlands; Emir Kusturica’s Yugoslav black-comedy epic Underground; Hou Hsiao-hsien’s beautiful if difficult Good Men, Good Women; Jim Jarmusch’s transgressive western Dead Man; Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon, an Iranian urban comedy about children that unfolds in real time; Zhang Yimou’s Shanghai Triad, a cross between Sternberg’s The Devil Is a Woman — with Gong Li taking the place of Marlene Dietrich — and Billy Bathgate; and Manoel de Oliveira’s The Convent (Ruizian metaphysics and theology with John Malkovich and Catherine Deneuve). Then there were such pleasures on the market as Gianni Amelio’s Lamerica, a mordant treatment of the collapse of communism in Albania; lively low-budget musicals by Jacques Rivette and Joseph P. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1995). — J.R.

This is the first Robert Benton movie I’ve really liked — and possibly my favorite Paul Newman performance since The Hustler. Based on a Richard Russo novel and set in upstate New York, it has both the poetry and the authenticity of failure, describing a community of fuckups headed by a 60-year-old part-time construction worker (Newman) who left his family decades earlier, and including his pathetic assistant (Pruitt Taylor Vince), his mean-spirited occasional employer (Bruce Willis at his best), the latter’s neglected wife (Melanie Griffith), and an ineffectual one-legged lawyer (Gene Saks). Conceived somewhat in the spirit of Chekhov’s stories, this 1994 feature ambles along semiplotlessly, focusing on the petty love-hatreds that link people together in small towns and the everyday orneriness that keeps them alive; it becomes only slightly less compelling when it develops a plot about the hero belatedly making peace with his abandoned son and one of his two grandsons. For better and for worse, it’s still a Hollywood movie (and a white boys’ movie to boot), but one with a more alert eye and feeling for American life than most of its competitors. With Jessica Tandy (in one of her last performances) and Dylan Walsh. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1993). — J.R.

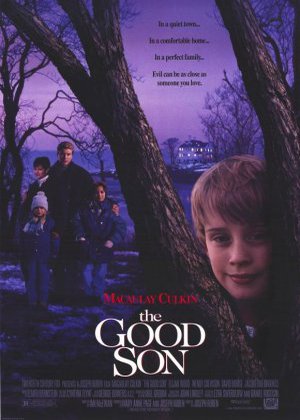

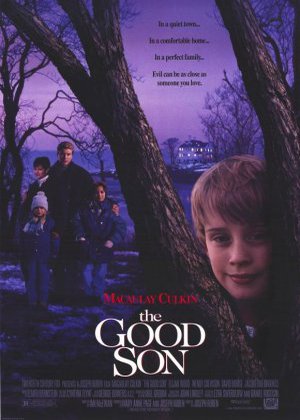

THE GOOD SON

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Joseph Ruben

Written by Ian McEwan

With Macaulay Culkin, Elijah Wood, Wendy Crewson, David Morse, Daniel Hugh Kelly, and Quinn Culkin.

The innocent-looking child who’s really evil incarnate is a natural idea for a horror movie, but getting us to believe in such a character isn’t as simple as it might sound. Ray Bradbury had a relatively easy time of it in “The Small Assassin,” a short story first published back in 1946 about an infant who murders people, because babies are somewhat mysterious and hence easier to project abstract notions on. In The Good Son, a mainly unconvincing thriller offering us 12-year-old Macaulay Culkin as evil incarnate, there are actually two problems — accepting Culkin as a child and accepting him as evil. Perhaps what we mean today by both “child” and “evil,” ideologically speaking, is at the root of the problem.

The hero of The Good Son is another boy of roughly the same age, Mark (Elijah Wood), living in the southwest, who has been traumatized by the recent death of his mother. Shortly before she dies she tells him, “I’ll always be with you,” and Mark interprets this to mean that she’ll come back to him as someone else. Read more

The following are my responses to questions from Alvaro Arroba about Kiarostami for the Spanish film magazine Letras de Cine that wound up appearing in Spanish in their 7th issue, in 2003. I’ve taken the liberty of slightly revising the English in a few cases, hopefully while respecting the meanings that Alvaro had in mind. –- J.R.

1- WHICH IS THE FIRST ABBAS KIAROSTAMI FILM YOU SAW? AND WHAT WAS YOUR FIRST REACTION TOWARDS IT? The first Kiarostami film I saw was LIFE AND NOTHING MORE at the Locarno International Film Festival, and it struck me immediately as a masterpiece. I was impressed by the film’s profound meditation on how to perceive and deal emotionally with a disaster, as well as by the use of long shots, which reminded me especially of the philosophical distance of Jacques Tati: not always knowing what to look at in a busy frame is sometimes a way of trusting in the choices and imagination of the spectator, and for me Kiaroistami in this film and Tati in PLAYTIME are both masters in this highly ethical game….I also have to admit with embarrassment that when I saw my next two Kiarostami films, CLOSE-UP and WHERE IS THE FRIEND’S HOUSE?, Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 505). A tinted restoration of this film was presented at Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato with a beautiful, large-orchestra score composed and conducted by Timothy Brock a few years back, and I must say that this very impressive presentation substantially transformed my original skepticism, fully demonstrating how much difference a serious archival restoration can make. And Flicker Alley has brought out this version on a lovely Blu-Ray, which I can heartily recommend. — J.R.

Feu Mathias Pascal

(The Late Mathias Pascal)

France, 1925

Director: Marcel L’Herbier

Miragno, Italy. Acting on behalf of herself, her son Mathias and her sister-in-law Scolastique, Maria Pascal authorises agent Batta Maldagna to sell her property; worried about her debts, he sells it at one-sixth its value. Mathias’ shy friend Pomino, secretly in Iove with Romilde Pescatore, asks Mathias to propose to her on his behalf at a village fête. Discovering that she is-in love with himself, Mathias marries her instead, but soon finds his life made miserable by his shrewish mother-in-law, who holds sway over Romilde. He goes to work at the chaotic municipal library, where his time is largely spent contriving to catch rats. After the nearly simultaneous deaths of his mother and infant daughter, he flees to Monte Carlo, where, by following the advice of a gambler who tells him to bet on 12, he unexpectedly wins a fortune. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). -– J.R.

Italy, 1973

Director: Fernando Di Leo

Sicily. Under orders from Mafia chieftain Don Corrasco [Richard Conte], Nick Lanzetta [Henry Silva] sneaks into a projection booth to murder most of Cocchi’s gang of mobsters while they are watching a pornographic film. The next day, other members of the Cocchi gang kidnap Rina [Antonia Santilli], the teenage daughter of Daniello, a high-ranking member of the Corrasco clan, offering to spare her life in exchange for her father’s. Corrasco refuses to abide by this trade, despite Daniello’s willingness, and orders Lanzetta to kill him if he tries to negotiate a deal — an eventuality that shortly comes to pass. Police officer Torri, while investigating the screening room massacre, is severely chastised by his chief Questore for tapping the phones of the members of the rival clans. Meanwhile, Rina is enjoying her captivity — particularly sex with her captors, whom she takes on singly and in pairs. An informer tells Lanzetta the address of the hideaway, and after the former is murdered for spite, Lanzetta kills Rina’s captors and takes her to his own flat, where he is shocked to discover her unshaken by Daniello’s death and eager to seduce him. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, Vol. 43, No. 509, June 1976. — J.R.

Sonny Rollins

(Sonny Rollins Live at Laren)

Netherlands, 1973

Director: Frans Boelen

The essential value of this film made for Dutch TV — a non-nonsense recording of the Sonny Rollins Quintet performing four numbers at the “International Jazzfestival” at Laren in August 1973 — is the music itself, and the unusual courtesy with which it is treated by the film-makers. Apart from a few brief pans across enthusiastic members of the audience, all the action is centered on stage, and the various angles caught by the two cameramen — each of whom is occasionally glimpsed in footage shot by the other — are all admirably related to a direct appreciation of the music, with none of the attempts to pump up excitement artificially that infect most jazz films, from St. Louis Blues (1929) to Jammin’ the Blues (1944) to Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1959). Rollins, playing very close to the top of his form in recent years, begins “There Is No Greater Love” with one of his imaginative a capella intros before launching into the theme in medium tempo; serviceable solos follow from Matsuo [guitar], [Walter] Davis [Jr.] Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 2001). — J.R.

Bearing in mind Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, this astonishing 230-minute epic by Edward Yang (1991), set over one Taipei school year in the early 60s, would fully warrant the subtitle A Taiwanese Tragedy. A powerful statement from Yang’s generation about what it means to be Taiwanese, superior even to his recent masterpiece Yi Yi, it has a novelistic richness of character, setting, and milieu unmatched by any other 90s film (a richness only partially apparent in its three-hour version). What Yang does with objects — a flashlight, a radio, a tape recorder, a Japanese sword — resonates more deeply than what most directors do with characters, because along with an uncommon understanding of and sympathy for teenagers Yang has an exquisite eye for the troubled universe they inhabit. This is a film about alienated identities in a country undergoing a profound existential crisis — a Rebel Without a Cause with much of the same nocturnal lyricism and cosmic despair. Notwithstanding the masterpieces of Hou Hsiao-hsien, the Taiwanese new wave starts here. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 13, 2007).

Both of these films, the more recent One Way Boogie Woogie 2012, and Benning’s earlier 11 X 14 are available in one two-disc DVD set from www.edition-filmmuseum.com/. — J.R.

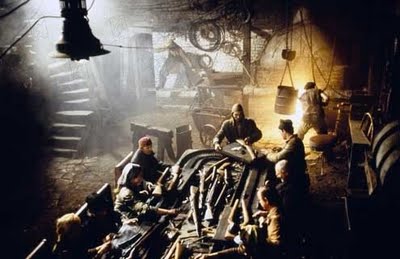

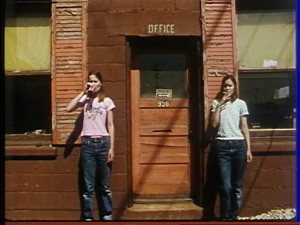

Titled after Piet Mondrian’s painting Broadway Boogie Woogie, James Benning’s experimental masterpiece One Way Boogie Woogie (1977) consists of 60 one-minute takes shot with a stationary camera in an industrial valley near his native Milwaukee. The film strikes a graceful balance between abstraction (either found or created) and personal history, with ingenious uses of on- and offscreen sound, and it plays like a portfolio of 60 miniature films, each a suspenseful puzzle and a beautifully composed mechanism. A few years ago Benning returned to his hometown to fashion this shot-for-shot remake (2005), planting his camera in the same places and, whenever possible, using the same people. It screens on a double bill with the original, and though it’s not on the same level, it’s a poignant and fascinating companion piece. Sat 4/14, 7 PM, Univ. of Chicago Film Studies Center.

Read more

Read more

From the Bard Observer, September 9, 1964. -– J.R.

What We Ate in That Year

A MOVEABLE FEAST, by Ernest Hemingway, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 211 pp., $4.95.

In the spring of that year, long after he was dead, a book of his was published and it was a good book. He had not written a good book for quite some time and the critics were beginning to worry. They had wanted to say something good about him now that he was dead, but there were no good books to say good things about except for those written twenty and thirty years ago, and they (the critics) had already spoken enough about the earlier ones anyway.

The new book was about Paris of long ago when he and his friends were writing the earlier books. In those days there was Miss Stein and Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis and Ford Maddox Ford and several others. Some were good and some were very good and others were not so good at all. He was not like the others because he was not a homosexual or an alcoholic and he did not have bad breath or look evil. Much of the time he would write, and during the times that he would not write he would walk the shaded avenues or go to the races. Read more

From American Film (September 1978). -– J.R.

Talking about avant-garde film these days raises a quandary. For one thing, no one can agree on precisely what the label means. Start by asking the proverbial man on the street what an avant-garde movie is. Chances are, if you don’t get insulted, the description that’s offered won’t exactly be a heartening one.

On the other hand, address your query to “an avant-garde filmmaker,” and you’re just as likely to get a moralistic distinction between art and commerce — or between art and entertainment calculated to shrivel your own sense of seriousness to the size of a pea.

The fact that there are such disagreements about simple definitions only helps to keep the term loaded and half-cocked. A Cuban director at a film festival once allegedly shunned an American director’s gesture of friendship by saying, “I only talk to people with guns. My film is a gun; your film isn’t. ” In analogous fashion, the mere concept of avant-garde film is often used as a gun by friends and foes alike. This scares off countless spectators who fall in between these categories — less committed souls who understandably run for cover as soon as any shots are fired. Read more