For me, the two best talking heads in Sacha Jenkins’ recent documentary, Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues, are those of Orson Welles and Ossie Davis, both of whom significantly started out as performers and theater people. Welles — whom we hear as the film begins, warmly introducing Armstrong as a friend on a TV talk show, explaining that he once planned to make a film that would recount the history of jazz through Armstrong’s life — insists on his preeminence as a performer “not on the principle of escapism but on the principle of affirmation.” Given that the entire career of Armstrong as a blazing maestro of the cornet and trumpet can be summed up by the word “affirmation”, Welles’s introduction couldn’t have been more apt.

Written for the first paper issue of New Lines Magazine, January 15, 2023. (Note: The version posted here is somewhat different.)

Ossie Davis, who once had a character in his play Purlie Victorious say to someone, “You’re a disgrace to the Negro profession,” recalls that he and his friends used to laugh derisively at Satchmo’s performing antics and clowning as a creepy form of Uncle Tomism until the two of them worked together on a movie, A Man Called Adam (1956). Sitting with Armstrong in a dressing room, Davis was struck by how sad the man looked during a reflective “off” moment until he was called back to work and snapped back into his signature toothy grin, suddenly alerting Davis to the sort of behavior his own black parents and grandparents had had to display in order to survive. Thereafter, he admits, he never laughed at Satchmo again.

Clearly, dealing with Louis Armstrong today necessitates dealing with a complicated historical past, sometimes even personally if you’re a white Southerner such as myself. A few days before my fourteenth birthday, in 1957, I attended a Louis Armstrong concert in Sheffield, Alabama—the 7 o’clock show for “whites,” not the 9:30 one for “colored”, according to the Jim Crow laws and protocols of the time—although I don’t know if the colored tickets were cheaper than those for the whites, as they were at the segregated movie theaters in town. But I do recall that Armstrong played in Sheffield with Barrett Deems, the white drummer in his band for many years, and Satchmo was most likely the only jazz musician able at the time to play in a racially “mixed” group in the Deep South (apart from the pitifully few venues held in that period for the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which lost most of its playdates due to its insistence on retaining its black bassist, Eugene Wright). But even Armstrong was taking a risk with Deems. On the same 1957 Southern tour, in Knoxville, Tennessee, a bomb exploded outside an Armstrong All-Stars concert, and Satchmo diplomatically stepped up to the microphone and said, “That’s okay, folks—it was jus’ my phone ringin’.” Recalling Welles’ introduction, what could be more affirmative than that?

He grew up at an international crossroads — New Orleans at the dawn of the twentieth century — nurtured in turn by his unmarried prostitute mother who sang in church, a family of Jewish Lithuanian rag merchants who helped him purchase his first cornet, and even a reform-school orphanage just outside the city with military-style discipline that he was sent to after firing his mother’s pistol on New Year’s Eve. Armstrong later recalled his time at the orphanage fondly and even nostalgically, perhaps because it gave order and purpose to a life that had up until then been mainly chaotic. And even if he hadn’t been born on July 4, 1900, as he later claimed (his registered birth was actually on August 4, 1901), the symbolic myth seemed appropriate, especially once he arguably became the most recognizable and appreciated American and artist on the planet – the universal embodiment of both freedom and art that was associated with his origins, perceived more as American than as African. Although it’s impossible to quantify the full reach of such a reputation. it appears that Armstrong’s world-wide fame reached its peak around the middle of the twentieth century when he started to tour for the U.S. State Department.

As an autodidact who authored his own memoirs without collaborators, he comprised a veritable monument to the American art of self-invention, and insofar as the art of jazz improvisation that he helped to create and popularize is one in which spontaneity equals a form of honesty, his ongoing self-creation was both audible and visible to everyone. This made him especially eligible to become America’s good-will ambassador around the world, a role that his status as a jazz pioneer only helped to foster.

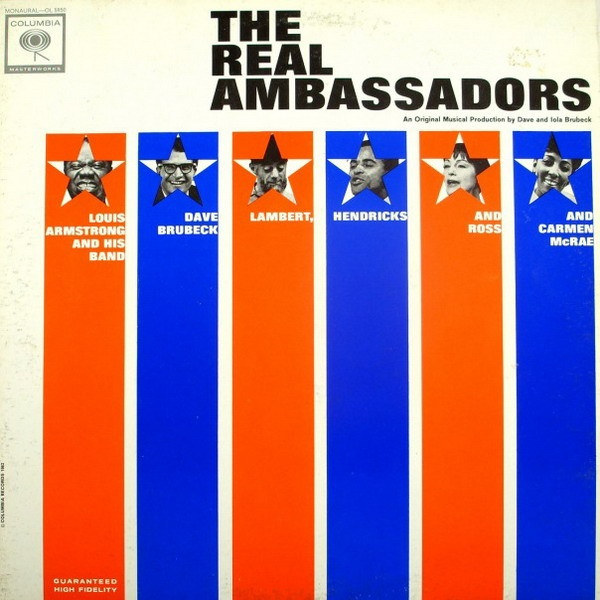

This became acknowledged, celebrated, and in a musical concocted by jazz pianist Dave Brubeck and his wife Iola that premiered at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1962 and became an ambitious soundtrack album the same year. It featured Armstrong, Brubeck’s Quartet, the vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks & Bavan, and Carmen McRae, with music by Brubeck and lyrics by his wife, and dealt with such Issues as America’s place in the world during the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, the image and nature of God, and the music business. Set in a fictional African country, The Real Ambassadors on CD features Armstrong as its star and central character, with his shining trumpet and his gravel-mouthed vocals delivering the memorable Brubeck score.

The implication was that Armstrong, like America, was a beacon for the whole world. But If you belong to everyone in the world, this means, in effect, that you’ve taken or at the very least assumed a particular position in relation to that world. And if you belong to the American mainstream, it could be argued that the easiest way to be political without creating a disturbance is to pretend that you have no politics at all. The European lesson for this very American form of self-deception is that claiming to have no politics ultimately means adopting the sort of bad politics that entails accepting the status quo. This was far from being the message of The Real Ambassadors, but for many people even today, it often registers as the Armstrong persona.

To believe, as Ossie Davis once did, that Armstrong’s racial politics were set by the mercenary white folks who succeeded the slave owners was to believe that those politics were reactionary, that even Satchmo’s duet with Barbra Streisand on “Hello, Dolly!” or his crooning “It’s a Wonderful World” was corny and shopworn. And it’s worth noting that Armstrong’s dislike of bebop – expressed in one interview as his enthusiastic preference for Guy Lombardo, a nonjazz bandleader associated with mainstream schmaltz—probably had as much to do with the lifestyles of beboppers as it did with modernist musical forms. (Moreover, as someone who happily imbibed marihuana daily, he had no bones about hiring and befriending bebopper Dexter Gordon, a fellow grass smoker.) As recounted by one of his biographers, the late Terry Teachout, a former jazz musician himself, “Except for [Dizzy] Gillespie, whose jokey demeanor on the bandstand was more like Armstrong’s than either man cared to admit, the boppers disdained the showmanship that was his trademark. More than a few of them were heroin

addicts (that was what he had in mind when he spoke of their ‘pipe-dream music’) whose habits made it impossible for them to conduct themselves with the professionalism that was his byword. Above all, though, their music was uncompromising in a way that he saw as threatening to the public’s acceptance of jazz.”

Yet Armstrong’s own musical genius could attain a burning and cascading complexity of its own–at least in his early recordings, and more fitfully afterwards. To my untutored ear, his famous cadenza at the start of his “West End Blues”, recorded with his Hot Five in 1928, even anticipates some of the multifaceted virtuoso breaks of Charlie Parker, the supreme bebopper, two decades later, rhythmically as well as melodically. Teachout, for instance, points to “a shift of gears known to contemporary classical composers as a ‘metric modulation’, in which he turns a single beat in the second measure…into two-thirds of a beat in the third measure.”

Armstrong’s ascent from the bottom of society to the top of the music world suggests a certain parallel with the career of another Charlie and another autodidact, namely Chaplin, although the differences are as salient as the similarities. Chaplin’s leftist politics were plainly visible, along with his sexual lifestyle and wealth, and these eventually led to him being barred from re-entry into the United States in 1952. Armstrong, by contrast, continued to live by choice in a working-class neighborhood in Queens, and, quite the opposite of Chaplin, left all his business decisions, including the hiring of his sidemen, to his Jewish manager, Joe Glaser, a former associate of Al Capone whose mob connections helped to protect Armstrong from the gangsters who wanted to control his career. One might add that Glaser’s handling of the Satchmo trademark continued to protect and shelter his client from the uglier aspects of capitalism. “I never tried in no way to ever be real real filthy rich like some people do,” Armstrong wrote, “and after they do they die just the same.” Yet by the same token, Glaser, who also became the manager of Brubeck and Billie Holiday, protected Armstrong from the controversy that would have come from expressing his political views more openly. These were privately expressed in many of the tape recordings that Armstrong made for friends and for his own amusement, and Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues allows us to hear several lively patches from them.

Yet he also made “When it’s Sleepy Time Down South” one of his theme songs, with its reference to “darkies [who] dance till the break of day”—even though he started to substitute “people” for “darkies” during the 1950s. But it was during that same decade, during the racial turmoil over school integration in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, that he broke with precedent by calling the much-beloved Dwight D. Eisenhower a “two-faced” President with “no guts” in an interview with a journalism student. He went on to call Arkansas governor Faubus a “no-good motherfucker,” assigned the same epithet to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and canceled on the spot his planned tour of the Soviet Union for the State Department, saying, “The way they are treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell.”

He refused to retract his statement, but three years later, he unknowingly traveled to the Congo at the behest of the CIA., who, as reported by historian Susan Williams in her recent book White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa, cynically used Armstrong as a “Trojan Horse” for furthering its interests, which included acquiring uranium and assassinating the Congo’s first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. This was the likely low point of the use of Armstrong’s good will as an unwitting and innocent tool of Cold War propaganda and skullduggery.

After his 1957 outburst, he mostly restricted his dissenting comments to his tape recorder, preferring to send out his message of love to everyone.I find it difficult to blame him for this. Even when he dressed his love and his celebration in the trappings of tired clichés and outworn stereotypes, I assume he believed that they still meant something—an assumption that carries a particular amount of weight today, in a divided country where everything that its populace shares and commonly reveres tends to be overlooked or else minimized by deafening and fearful battle cries.

The problem is, mainstream politics in the U.S., whether it’s leftist or conservative or (most often) scrambled, abounds in linguistic misrepresentations and historical gaps and confusions while being expressed almost exclusively in the form of light entertainment. Satchmo saw himself as an entertainer as much as Donald Trump does, but the messages of the two are hardly the same, and the language we have to express our own views seems even more inadequate than it was in the 1950s. Most American “blacks” are actually brown, alleged “whites” are brownish pink, it’s politically incorrect to identify Barack Obama as half “white” (which he is), and the U.S. military occupation of Iraq is usually called “the Iraqi war” or “the war in Iraq” to make it sound more respectable. Even the term “America” imperialistically collapses North America, Central America, and South America into the so-called United States. With a language already full of such deceptive half-truths and deceptions, the banning of a passionately antiracist novel, Huckleberry Finn, as racist or “insensitive” by various school boards becomes easier to understand as an ahistorical grasp of language that ignores its changing connotations whereby “Negro” ceases to become an acceptable term and is replaced by the less accurate “black” because it reminds too many people of the N-word, which was once regarded as more commonplace and neutral.

Satchmo’s art and gift to us is the happiness of cameraderie, expressed musically, personally, humorously, honestly, and at its best, spontaneously. Its morality is not very different from Huck Finn’s code of loyalty to an escaped slave who is also a pal. Coming from a culture that arose out of slavery and social rejection and finding delight in its discovery of freedom, it’s something we should all continue to cherish.