Commissioned by Fandor Keyframe in late January 2016. — J.R.

Mark Rappaport and I have been friends for well over three decades. He’s a year older than me, and even though our class and regional backgrounds differ, we’re both film freaks and film historians who grew up with the same Hollywood iconographies, for better and for worse. How these experiences might qualify as better or worse have been the source of countless friendly arguments, all the more so when they converge on the same objects of fascination — as the title of his latest video puts it, Debra Paget, For Example.

Thirty-six minutes and thirty-six seconds long, this juicy video about the 15-year screen career of Debra Paget (1948-1963, ages 14 to 29, including a busy eight-year stretch as contract player at Fox, 1950-1957) seems at times to cover almost as much material and as much cultural ground as Rappaport’s two star-centered film features, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992) and From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995), both of which I’ve reviewed in the past. (See www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/1992/11/rock-criticism and www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2022/12/riddles-of-a-sphinx for specifics.) It might even be called a compendium of Rappaport’s rhetorical strategies, such as using an actor to play the star in question — as in those two features, although here only offscreen (as was also done in his brilliant recent video I, Dalio, or The Rules of the Game), with Paget voiced by Caroline Simonds — and using Rappaport’s own voice, as in another recent video, The Circle Closes. One might say that the reason why he employs two voices is what academic critics would call discursive: he has more to say, and this “more” can’t be contained within a single voice; it also wanders every which way, as many of the best essays do. And to complicate matters, these two voices aren’t so much in dialogue with one another as they are coming at us from different angles — fictional in the case of Simonds speaking as (or for) Paget, non-fictional in the case of Rappaport speaking for himself — even though the two of them share the same basic assumptions.

The voices aren’t exactly in conflict, but they nonetheless point towards a divergence of positions that seem to make the two voices necessary. Let’s call it a divided consciousness, marking a breach that I fully share with Rappaport. This divergence can be described in many different ways — e.g., as art versus kitsch, as history versus memory, as reality versus fantasy, and maybe even as theory versus practice. Here is how Rappaport himself expresses the problem, roughly halfway through the video, starting with a parenthetical digression about Maria Montez in the 1940s and ending with the Golden Calf sequence in The Ten Commandments:

“She [Maria Montez] was called the Queen of Technicolor, but that was a euphemism. What they meant was the Queen of Kitsch….But we’re less likely to scoff at present-day kitsch, or even recognize it. In fact, we often embrace it.

“If Maria Montez was the Queen of Kitsch, surely Debra Paget is the Princess of Kitsch. But let’s be careful here. One guy’s kitsch is another guy’s nostalgia.

“If you saw these movies at the right age, at a Saturday matinee or on TV when you were a kid, it would have made all the difference. And it’s virtually impossible to explain it to other people who aren’t there. You can’t argue with someone’s childhood memories. And who’s to say that kitsch — or memories — or nostalgia, and the seemingly guilty pleasures they offer — are any less valuable in film history than, say, Ingmar Bergman or Antonioni? The jury’s still out, and won’t be in for awhile. For example — ”

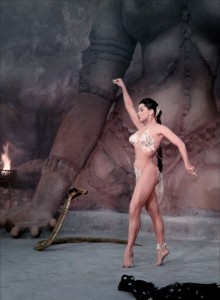

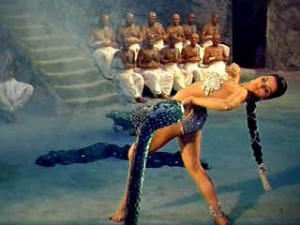

Over the three labeled sections of Debra Paget, For Example — “1. Beginning,” “2. The Middle Years & CinemaScope,“ and “3. Fritz Lang’s Indian Film/Paget’s Apotheosis” — the topics and positions towards them are indeed disparate. In the first part alone, among other things, we get Paget’s skill in walking across a room (“not as easy to do as you might think”); then we get the queasy implications of 14-year-old Paget kissing a 38-year-old Richard Conte playing a gangster, in her first screen appearance in the 1948 Cry of the City (expressed by Rappaport and then seconded by Simonds, asking, “Why is my mother allowing this?”); we hear about Paget’s mastery of “the sorrowful Madonna look” being both “a blessing and a curse”; Paget being cast in diverse ethnic parts (Italian, Native American, Polynesian); her skills as singer and dancer and her Vegas nightclub act; her playing second fiddle to Jean Peters in Anne of the Indies (1951) and her desire for bigger parts and full stardom. Then, in part two, we hear about some of the mixed blessings of CinemaScope (such as the absence of closeups, illustrated by a subdivision of the anamorphic frame into six medium shots of Debra), Elvis Presley’s marriage proposal (nixed by Paget’s mother) after they appeared together in Love Me Tender, diverse notations about Demetrius and the Gladiators and Princess of the Nile (both 1954), the latter of which gave her star billing for the first time, and much, much more.

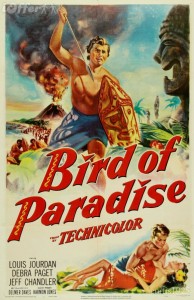

I should add that my own, equally divided psychosexual investments in Debra Paget were explored in the first chapter of my first book, an experimental autobiography called Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), centering on my encounter at age eight with one of Rappaport’s own privileged sites, Bird of Paradise (1952). Oddly enough, both our encounters are tied to Judaism: In my case, Paget’s upsetting fate as a Polynesian maiden ordered to dive into a live volcano as a sacrifice for her interracial involvement with Louis Jourdan was tied in a subsequent nightmare to familial sacrifices occasioned by my older brother’s bar mitzvah. Rappaport is mostly concerned with the Jewish identities of two other actors in the movie — Maurice Schwartz (as the Kahuna who orders Paget’s sacrifice), a major figure in Yiddish theater and Yiddish cinema, and Jeff Chandler (as Jourdan’s American pal), born Ira Grossel in Brooklyn, Rappaport’s home town.

The reason for bringing all of this up is to point out that, to paraphrase Rappaport, one guy’s kitsch is another guy’s Judaism, and vice versa, and similarly, one guy’s bad girl is another guy’s good girl. In part two, Rappaport claims that Paget wanted more bad-girl parts like Marilyn Monroe in Niagara (1953), adding that this was what made her a star, whereas I would suggest that it was also the impossible mixture of Monroe’s bad-girl smarts and her good-girl-innocence in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes the same year — which Rappaport also quotes from, but in a different context—that did the trick. And I would further argue that Debra’s best parts all combine certain elements of saucy bad-girl irreverence with good-girl Madonna-like sorrow — even in Bird of Paradise, where she breaks the tribal taboo. But I don’t mind him bringing up Niagara because it occasions a great line to accompany a shot of the heroine’s demise (“Marilyn — frozen in a trapezoid of death”), even if this has nothing to do with Debra.

In short, we’re talking here about a terrain where friendly quibbles are inevitable, and also ultimately irrelevant. I wasn’t fully convinced that European actress Yvonne Furneaux was a dead ringer for Paget who could have played her twin, as Rappaport claims, until I happened to resee Lisbon (1956) while working on this review, which for me proves his point better than his own examples — but maybe that’s because we view both actresses differently. I can’t buy Rappaport’s claim that Paget refused to give interviews after she ended her acting career after coming across two such interviews on YouTube (both concerned in part with her faith as a Christian), but of course one gal’s acting career can turn out to be the same gal’s religion (or vice versa) years later.

Furthermore, although I’m quite happy to call Lang’s two-part Indian feature in 1959 “Paget’s Apotheosis” — even when it ushers in another long digression about Billy Daniel’s choreography (which allows for still another digression about Daniel’s boyfriend Mitchell Leisen, another Rappaport favorite) — I would personally nominate another Paget dance with a different sort of voluptuous bump-and-grind as her erotic apotheosis: namely, her burlesque, bad-girl performance of “Father’s Got ‘em” in John Phillip Sousa’s parlor in the 1952 Stars and Stripes Forever, which allows her to sing as well as dance, with an equivalent number of shocked reaction shots. But this doesn’t make me regret Rappaport’s alternate choice, which permits him to add a riff about Paget’s revenge on a snake erection in The River’s Edge (1957), which further demonstrates that one guy’s snake is another guy’s erection (and vice versa). And even if he omits Fritz Lang’s most erotic picture (Spione, 1928) while surveying his silent films, I can readily forgive him, because he also includes ravishing bits of two other versions of The Tiger of Bengal and The Indian Tomb that preceded Lang’s own, neither of which I’d seen before.