Monthly Archives: January 2023

Saint Omer

Like almost every other year within recent memory, I wind up seeing a masterpiece after I can vote for it or include it in any poll. Alice Diop’s first fiction feature is a classical example of a film that asks questions more than provides answers, and one of its best ways of posing or suggesting questions is not cutting to a reverse angle whenever you’re expecting it to. This is a film carried largely by its close-ups and its dialogue, and many of its reverse angles are between its two protagonists, two young and black Senegalese women in France who never meet, although they do exchange glances at one climactic, privileged moment. It’s a film devoted to a trial whose outcome is never recorded, but it has generated enough questions by the end to make a verdict seem either impossible or superfluous. Consciously or not, it carries more than one echo of Ousmane Sembene’s great La noire de… (Black Girl, 1966). [1/3/2023]

Twilight

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1992). — J.R.

A dirgelike Hungarian thriller by Gyorgy Feher about the search for a serial killer whose victims are little girls. The striking visual style (high-contrast black-and-white cinematography by Miklos Gurban) and creepy pacing tend to dominate the plot so thoroughly that I found myself tuning the narrative out and not being terribly worried about what I was missing. While the slow-as-molasses dialogue delivery and camera movements superficially suggest Tarkovsky (or, closer to home, Bela Tarr’s Damnation), Feher’s script and mise en scene are considerably more mannerist — employed more to conjure an atmosphere than to convey a particular vision or a distinctive moral universe. The closest American equivalent to this sort of exercise might be Rumble Fish: sumptuous visuals that impart more filigree than substance (1990). (JR)

Program Note on OUT 1

Written for the Vancouver International Film Festival, and published September 30, 2006. — J.R.

The Violent Years

From The Movie No. 71, 1981. — J.R.

From Psycho and Spartacus (both 1960) to The Wild Bunch and Easy Rider (both 1969), the Sixties might be regarded as the period when screen violence gained a new aesthetic self-consciousness and something approaching academic respectability, at least in the public mind. To put it somewhat differently, the contemporary spectator of 1960, shocked by the brutal shower murder of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in Psycho as an event — without observing that it was a composite film effect created by several dozen rapidly cut shots –- would have been much likelier to notice, in 1969, the use of slow motion in the depiction of several dozen violent deaths in The Wild Bunch.

The key film document of the decade, endlessly scrutinized and discussed, was not an entertainment feature at all, but the record of an amateur film-maker named Abe Zapruder of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963; the close analysis to which this short length of film was subjected was characteristic of a changing attitude towards the medium as a whole.

In the Sixties many established cultural, social, and political values were radically thrown into question, at the same time that the media -– including television and pop music as well as cinema — were becoming closely examined in their own right. Read more

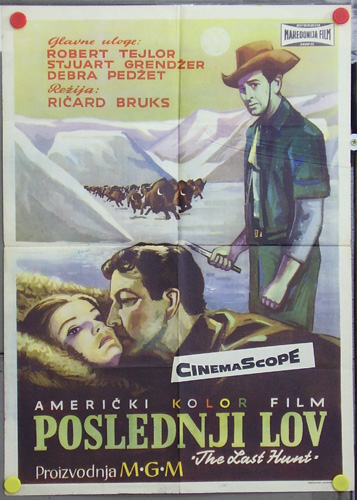

Richard Brooks’ THE LAST HUNT

THE LAST HUNT (Richard Brooks, 1956, 108 min.)

A very dated but absorbing – and, in its own terms, effective – liberal CinemaScope western, all the more interesting for its dated qualities. In anticipation of Jim Jarmusch’s DEAD MAN, an explicit correlation is made between genocide of Native Americans and the decimation of buffalos, personified in this case by a racist and wanton killer played by Robert Taylor -– contrasted with the humane, reluctant buffalo killer played by Stewart Granger, who grew up with Native Americans and respects both them and their own respect for white buffalos, unlike Taylor. Lloyd Nolan plays the Walter Brennan part, a drunken old geezer who also comes along on the last hunt and winds up siding more with the good guys (i.e., everyone except Taylor, a dyed-in the-wool villain throughout).

The politically incorrect monkey wrench tossed into this scheme, at least by today’s standards, is the fact that the two major Native American characters are played by Russ Tamblyn (a half-breed) and Debra Paget, who function as Granger’s son figure and romantic interest, respectively. In short, no real Native Americans to be seen anywhere, making this movie a good target for the kind of conservative, anti-liberal scorn that a critic like Manny Farber might have had towards such a film. Read more

The Films of Vincente Minnelli

From Cineaste, Fall 1995. — J.R.

The Films of Vincente Minnelli

by James Naremore. Cambridge University Press, 1993. 202 pp, illus., Hardcover: $65.00. Paperback: $27.99.

The critical position of James Naremore is Frankfurt school auteurism, a seeming contradiction. That is, he shares the Marxist orientation of many Frankfurt school intellectuals but not their disdain for the artifacts of mass culture. (To be sure, not all Frankfurt school members can be characterized in quite so monolithic a fashion; see, for instance, the prewar journalism of Siegfried Kracauer published this year in The Mass Ornament.) As a consequence, Naremore’s work shows an interest in style and pleasure that runs against the puritanical grain of most American Marxists, without ever losing sight of the social and political issues avoided by most American auteurists.

This is an idiosyncratic and progressive book in a series, the Cambridge Film Classics, that has mainly been conformist and conservative, especially in relationship to non-American filmmakers. Its volumes always focus on a few “representative” features rather than complete oeuvres, and Naremore’s study of Minnelli focuses on Cabin in the Sky, Meet Me in St. Louis, Father of the Bride, The Bad and the Beautiful, and Lust for Life, but only after an Introduction and first chapter that take up a quarter of the book and lay a considerable amount of contextual groundwork. Read more

Cartoonal Knowledge

From The Soho News (June 11, 1980). I’m sorry I haven’t had better luck in finding illustrations for the experimental and independent animated shorts reviewed here. But at least if you hit the first illustration, you can see it move. — J.R.

New American Animation

Film Forum, June 12-15 and l9-22

Cartoonal Knowledge

Thalia, Mondays (June through August)

Did you ever step out of a movie theater in the good old days and exclaim, “Gee, that cartoon was better than the feature”? Whether you did or not, there’s precious little chance of such a thing happening today. Thanks to some of the packaging principles that currently dominate media, short animation is often treated like a ghetto art — quarantined in its own little category and asked to stay there, mind its manners and keep a low profile, in such out-of-the-way corners as kiddie matinees and museums.

Consequently, to write about the New American Animation series at Film Forum — the last program for the season — is a bit like having to write about the Third World (another Film Forum specialty), rather than, say, simply Brazil or Algeria. And Greg Ford’s massive “Cartoonal Knowledge” series at the Thalia – encompassing 13 Mondays this summer, and billed as “probably the largest and most comprehensive cartoon festival ever mounted in a straight ‘theatrical’ context” — etches out an umbrella subject that is equally daunting to nonspecialists. Read more

May the Force Leave Us Alone [on THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK]

From The Soho News, May 21, 1980. — J.R.

The Empire Strikes Back

Story by George Lucas

Screenplay by Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan

Directed by Irwin Kershner

Let’s face facts. Whether you or I love, hate or feel indifferent to The Empire Strikes Back — or any of the seven sequels and “prequels” to Star Wars slated to interfere with our lives over the next two decades — doesn’t make the slightest bit of difference in the long run, on the cosmic scale of things. Nor does it matter all that much in the mundane short run, either. Even if you stay away from the movie, manage to shun the novel and T-shirt and comic, avoid the soundtrack album and toys and video cassette, you can bet that a skilled team of disinterested humanitarians and technocrats, working round the clock with computers has decided that it’s so good for you and your kids that there’s no way you can prevent it from being crammed down your throats, in one form or another.

You’d better grin and bear it, if you know what’s good for you. The celestial machinery that has already turned Star Wars into the biggest grosser to date (“of all time” might seem a little excessive in forestalling the future) isn’t taking any chances in its investment by branching our or experimenting much. Read more