Written in late 2019 for Grasshopper Film’s digital release in 2020 of Pedro Costa’s masterpiece, recently selected as Portugal’s official submission for best international feature at the 93rd Academy Awards. — J.R.

“A film with no commercial prospects whatever,” lamented The Nation’s Stuart Klawans, in the course of his passionate defense, after it won both the Golden Leopard and best actress awards in Locarno and the Silver Hugo in Chicago, among other festival prizes. Soon afterwards, Film Comment announced on its cover, “Pedro Costa’s Breathtaking Vitalina Varela Goes to Sundance,” and it was also declared the best film of 2019 by Roger Koza’s international poll of 169 critics, filmmakers, and programmers, beating even Quentin Tarantino’s very-commercial Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood by eleven votes.

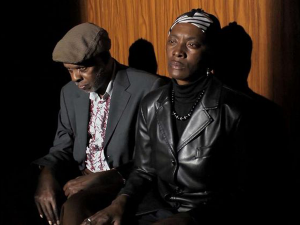

How to explain the appeal of a movie named after a real person, a displaced “non-professional” who is also its star? Or the nature of a film driven by its refusal to separate art from life or fiction from non-fiction — feeling more like a place to visit or a person to hang out with, and less like an event or a story?

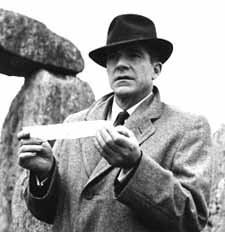

Seemingly shared by Film Comment and Klawans is the assumption that the fate of Vitalina Varela is tied to commerce — something we can assume as well about the fate of Vitalina the person. Even though many of us hate to admit it, capitalism isn’t exactly a victimless crime. We even become its casual victims as moviegoers whenever we watch a trailer in which we can’t tell who wrote or directed the picture because the credits race by too quickly for anyone but lawyers to read them — the assumption being that we’re too crude and stupid to care about such matters ourselves. Respecting us much more even while it ignores many of our desires for narrative clarity and closure, Vitalina Varela places itself in a different category from most Hollywood fare, even though Pedro Costa cites certain older commercial models — John Ford and Anthony Mann, Ernst Lubitsch’s Cluny Brown and Jacques Tourneur’s Curse of the Demon (all of them “movies” as opposed to “films”) –— among his treasured touchstones. So as victims we already share something with Vitalina, who’s also defined and manipulated by someone else’s economic concerns. Even her Cape Verdean neighbors in Lisbon shun her because her late husband was a crook, despite the fact that they all speak Creole, so that the dialogue of this movie also needs to be subtitled in Portugal and Brazil.

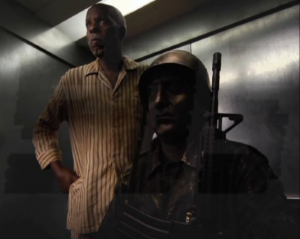

In the two previous extended chapters of Costa’s odyssey about displaced Cape Verdeans in exile, Colossal Youth (2006) and Horse Money (2014), Ventura is the central figure, playing himself. Here he’s replaced by Vitalina, but he also figures here as someone else–a fragile, deeply troubled and guilt-ridden priest, presiding over a ruined church (created by Costa in the ruins of a suburban movie theater) that Vitalina periodically visits.

Even though we often describe what’s artistic in terms of form or style or genre, what we feel and think are surely just as relevant. And both the emotion and the content of Vitalina Varelacan be described in terms of what’s there and what’s missing — Costa’s contributions (that is, his investments and expenditures) and our own.

At the first screening of Vitalina Varela in Chicago, there were about a hundred people and no walkouts, applause at the end, and many stayed through the final credits. At the second screening, about seventy showed up and a few left before the end, but I didn’t see anyone taking out her or his mobile. Although I wouldn’t call it an “easy” film, if only because it doesn’t cater to the usual demands of storytelling, I suspect it provides more difficulties to film critics than it does to ordinary viewers who choose to watch it. It’s really a matter of emotional and temperamental investment — what you choose to do with your time in its company.

Inventing its own rules, and therefore reinventing us as spectators in the process, it can’t be easily described in terms of plot because, like Horse Money (which introduced us to its leading lady and her arrival in Lisbon), it traffics in the sorts of memories that accompany mourning, and these tend to be constant undertows of mood and feeling — perpetual hauntings, so to speak — rather than flashbacks. As we learned in Horse Money and are told again in this film, Vitalina flew from Cape Verde to Lisbon to attend her husband’s funeral, but arrived only after it took place, and then moved into his ramshackle house. And the fact that Costa helped her to get her residency papers and chose to make a movie with and about her are two facets of the same impulse, so that we can’t really distinguish between wanting to do something worthwhile and wanting to make something beautiful — thus refusing the neat distinctions we usually make between good works (in the Christian sense) and good work (aesthetically speaking), as if they were somehow meant to be worlds apart.

Both the emotion and the content of Vitalina Varela can be described in terms of what’s there and what’s missing — Costa’s contributions (his investments and expenditures) and our own. And the intimacy assumed by Costa in order to tell Vitalina’s story — or, more precisely, to help her tell her own story — doesn’t rule out mystery, which pervades everything.. We don’t even know what caused her husband’s death, and Costa has admitted that he was afraid to ask Vitalina why she chose to remain in Portugal, adding that she has a son and daughter in Cape Verde — one of the many things that the film chooses to remain silent about.

Beginning and (almost) ending in a graveyard, Vitalina Varelaactually concludes back in Cape Verde on a note of relative hope, still thinking about a future. With a leading lady who does things with the whites of her eyes that I haven’t seen since the silent actresses of Erich von Stroheim and Carl Dreyer, and many different ways of collapsing (or expanding) the past into the present, exteriors into interiors, and a ruined movie theater into a ruined church, everything conspires to create a place that one inhabits rather than a story or a drift — a place that one finally has to help Vitalina to build or repair in order to find one’s own personal space inside it.