From the Chicago Reader (January 12, 1998). — J.R.

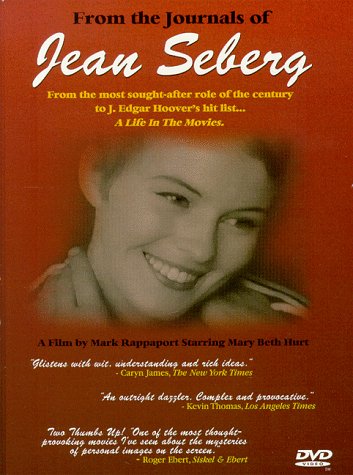

From the Journals of Jean Seberg

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Mark Rappaport

With Jean Seberg and Mary Beth Hurt.

For most of the remainder of this month the Film Center is presenting the U.S. theatrical premiere of Mark Rappaport’s From the Journals of Jean Seberg, and using this occasion to show some other important programs as well. We had revivals of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, featuring one of Seberg’s key early performances, and Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), both important touchstones in Rappaport’s film — the second as a cross-reference to Seberg’s first film, Saint Joan. This week, in addition to seven showings of From the Journals of Jean Seberg (to be followed by four more over the next couple of weeks), there are two screenings of a brand-new print of one of Rappaport’s best narrative features, The Scenic Route (1978), along with his remarkable 36-minute tour de force Exterior Night (1994) — a noirish narrative about film noir in which actors filmed in color walk around inside vintage black-and-white Warners sets and locations from the 40s and 50s, shot originally on high-definition video in Germany, and recently transferred to 35-millimeter film. (From the Journals of Jean Seberg, shot and edited on conventional video, has been transferred to 16-millimeter.) And on Friday and Saturday, January 26 and 27, the Film Center will be showing the Chicago premiere of Jacques Rivette’s two-part Joan the Maid (1993), another ambitious effort to tell the story of Joan of Arc, starring Sandrine Bonnaire.

Reviewing Rock Hudson’s Home Movies in these pages three years ago, I assigned all of the movie’s writing credits to writer-director Mark Rappaport, while including Rock Hudson himself, in addition to Eric Farr (the actor hired to represent Hudson discussing his own life), as a cast member. In the case of writing credits, I reasoned that even if Rock Hudson’s Home Movies used of some of Hudson’s own statements made in interviews, as well as movie dialogue (which was written by others) from numerous clips, it was Rappaport’s editing choices as well as his own text that determined the final meaning of the material. On the other hand, because we saw so much of Hudson as well as Farr in this film I felt it “starred” both of them, though Hudson made no decision to appear in it.

The same reasoning applies to From the Journals of Jean Seberg, an even richer work. It’s composed of the same sort of basic materials as its predecessor — an actor (Mary Beth Hurt) who plays Seberg, and is seen almost always in juxtaposition with the real Seberg, commenting on Seberg’s life while we look at clips from her features. (The commentary periodically moves beyond Seberg to take in the lives and careers of Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave, two contemporaries who like Seberg have been associated with radical politics.) In spite of certain methodological and stylistic similarities between Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992) and From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995), the new movie is by no means a spin-off, but a substantially different work with a mood and feeling all its own. A new kind of movie, and a highly entertaining one, it has created more of a buzz at festival screenings than anything else Rappaport has done in three decades of independent work (in a career now encompassing eight features and a dozen shorter works)–a response few would have predicted given the relative obscurity of its subject.

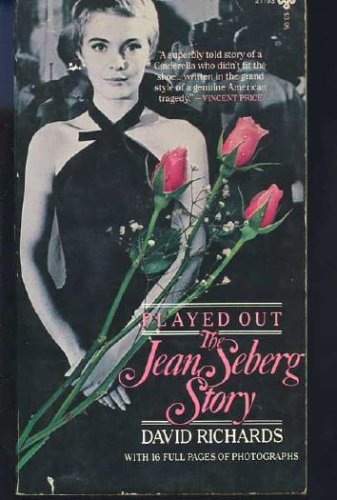

Many critics are referring to this movie as a documentary, a label I strenuously object to. However unorthodox the terms “fictional biography” and “fictional essay” appear, they come much closer to describing what Rappaport is up to. To call From the Journals of Jean Seberg a documentary is to imply that Seberg herself is speaking to us through it — a conclusion one can reach only if one subscribes to the pseudoknowledge proffered by pop journalism about movie stars. (For the record, Rappaport’s principal source, apart from films, is a single book, David Richards’s 1981 Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story — the only Seberg biography, written by someone who never met her.)

A suicide at 40, Seberg was hounded to death in 1979 by the FBI because of her work with the Black Panthers. When she became pregnant, J. Edgar Hoover planted a fallacious story in Newsweek that the father was black. The baby died and many nervous breakdowns and suicide attempts followed. Part of what made Seberg’s life and career so heartbreaking was that her early fame as a teenager seemed to carry so much promise. Her well-publicized debut as Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan — after a nationwide talent search that screened thousands of applicants before she was discovered in small-town Iowa — was followed by her fresh-faced roles in Bonjour Tristesse (1958) and Breathless (1959), which catapulted her to icon status, her close-cropped hair becoming a central fashion reference. She also acted in films by Philippe de Broca and Claude Chabrol, but got her only chance to do something interesting in an American picture called Lilith (1964); after that she was repeatedly wasted in mediocre French movies (four of them directed by her first three husbands) and Hollywood efforts like Paint Your Wagon and Airport, where she was usually miscast.

In Rock Hudson’s Home Movies — which was speculative but less obviously so — one could feel that Rappaport was adopting the convention of speaking for Hudson in order to speak about him. But in this film he is speaking for Seberg in order to say many things about many subjects. Seberg the biological individual is only one of these subjects, and only in a limited and somewhat problematic fashion. On the other hand, “Jean Seberg” as what certain academics would call a text or a textual trace — a cluster of signs and assigned meanings that most viewers have “read” as if they composed a biological individual, not a set of media signals–is very much the focus of this film. And learning to distinguish the real Seberg from the textual Seberg is one of the more valuable lessons this movie offers. One comes away from this film with a tragic sense that the real Seberg is not only unknown but unknowable, much as her textual counterpart often was. Perhaps her relation to the camera had something to do with this, as one of Rappaport’s fictional monologues obliquely suggests: “I was the first actress who returned the hard stare of the camera lens –and, at the same time, [was] aware that the camera was looking at me. In that sense, even if you didn’t hear of me, I became the first modern movie star.”

In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention two facts. One is that Rappaport is a good friend of mine and that we have argued at length about Jean Seberg before, during, and since the completion of this project. The other is that in Paris on the afternoon of March 17, 1973, I met Jean Seberg at her apartment on rue de Bac.

Not that it was an especially momentous meeting. A friend of mine who was a friend of Seberg’s had hired me to adapt a J.G. Ballard novel, The Crystal World, for a film treatment — the only scriptwriting I’ve ever done. After I did about half the work, the pages were shown to Seberg for a second opinion. Seberg had recently tried her hand at screenwriting and was interested in looking at some of the efforts of others. A meeting was called at Seberg’s flat. I arrived first, and was delighted to discover that Seberg — hobbling about in a plaster cast, having recently broken a leg — liked my treatment just fine (though I suspect it was mediocre at best; I had so little confidence that the film would ever be made that I didn’t even bother to make a copy of the treatment for myself). The upshot was that I was hired to complete the treatment. I still knew that the film would never be made, but from that point on I mentally cast Seberg as my heroine. During my visit to her apartment, I also met Seberg’s husband at the time, Dennis Berry (son of the blacklisted Hollywood director John Berry), as well as her former husband Romain Gary, who lived in the adjoining flat and happened to drop by.

The only other time I ever saw Seberg in the flesh was in late 1974, and then only from a distance. I was present at what may have been the world premiere of a short film she wrote, directed, and starred in, Ballad for the Kid, at the London film festival. Its text was highly indebted (though not credited) to Michael McClure’s play The Beard, and Seberg, who was present to introduce the film, played a character based on Jean Harlow interacting with a character based on Billy the Kid (played by a relative unknown, a young French actor) in an abandoned sandpit somewhere near Orly airport. It was a French hippie “underground” effort that resembled many others of that period, and though it was embarrassingly bad, the derision of the audience seemed needlessly cruel and vindictive. I remember thinking how painful it must have been for Seberg.

So much for my personal encounters with the biological Jean Seberg. I can’t say with any honesty that I knew her, but my limited acquaintance at least gave me some sense of who she wasn’t–specifically the witty, ironic, and analytical persona created by Rappaport and Hurt. But then again, in order for this film to say what it has to say and do what it wants to do, the biological Seberg becomes almost irrelevant; it’s the textual Seberg that ultimately counts. (Rappaport comes closest to acknowledging this when he has Hurt say, on the subject of Seberg appearing so often in humiliating film parts, “I was always a good girl and did what I was told….Maybe I was not smart, that was it. Or maybe I didn’t know how to read scripts. How else to explain why I was so complicitous in my own degradation?” The other possible or partial explanation he leaves out — self-hatred — apparently doesn’t jibe well enough with the persona he creates.)

Indeed, the curious achievement of From the Journals of Jean Seberg as art is that it makes the correctness of Rappaport’s positions about various matters — such as the value of Preminger’s Saint Joan and Preminger’s decision to cast Seberg in it and the easy “casting” of Romain Gary as a crass abuser and exploiter of his wife — only tangential to the film’s validity and success. For me, Seberg made a more effective and plausible Joan of Arc than 1957 reviewers were (or Rappaport is) prepared to recognize, and the bald assumption that Gary victimized Seberg (which implies that this was a one-way process) is a judgment that neither Rappaport nor I have the right to make on the basis of the limited information we have. But there are plenty of good aesthetic reasons for Rappaport asking (via Hurt) of Seberg’s Joan, “Who on earth would follow this drum majorette into battle?” and depicting all of Seberg’s directors and husbands as simple exploiters of her. And in fact, the textual evidence that Gary victimized her in his two features as a writer-director is irrefutable. (So is the evidence of what Roger Vadim and Tony Richardson did on occasion to show off their wives and mistresses on-screen, including Brigitte Bardot and Jane Fonda in several Vadim films and Jeanne Moreau in Richardson’s Mademoiselle, which leads to the following query: “What is it with these guys, who offer their wives as fodder for the sexual fantasies of millions of unseen men in darkened theaters? How many movies are there in which an actress directed by her husband plays a whore, a hooker, a prostitute, for the amusement of anyone with the price of a ticket?”)

Insofar as truth is seldom simple, I would even argue that the aesthetic rightness of Rappaport’s decisions in these matters leads to another kind of truthfulness that shouldn’t be dismissed. For the fact remains, despite all the cant that tries to persuade us otherwise, that ethical positions in this kind of filmmaking don’t exist independently from aesthetic positions. Rappaport has to construct a fictional Seberg in order to say truthful things about the life and image of the real one, and the beauty of the one he creates here is that, with Hurt’s poise and eloquence, she exists just long enough to make a few points and then vanishes — leaving behind only traces of the real and unknowable Seberg to confound us all over again.

There is a difference, however, between exploiting a biological individual and juggling a text, and for this reason I can’t go along with those reviewers who claim that Rappaport is guilty of manipulating Seberg in the same way that her directors and/or husbands did. In point of fact, the textual discoveries and manipulations in this movie are largely what’s so breathtaking about it. A masterful essayist in developing his arguments, Rappaport manages to justify every apparent digression with a remarkable set of continuities and coincidences. A considerable part of his emphasis throughout is on the ambiguity of Seberg’s blank expressions — a subject he eventually links to Clint Eastwood’s macho persona as the Man With No Name and Dirty Harry, commenting on the separate values this culture assigns to blank expressions in women and in men at the same time that he alludes to Seberg and Eastwood’s affair when they were costarring in Paint Your Wagon. Seberg’s ambiguity eventually leads to the mythical allure of the madwoman in her most ambitious performance (Lilith), whereas Eastwood’s ambiguity, combined with his famous terse one-liners, is traced through the presidential posturings of Reagan and Bush (“Read my lips” constituting merely the logical outgrowth of “Make my day”).

Following other aspects of the blank expression leads to a detailed discussion of the close-up and the famous experiment in editing conducted in 1923 by Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov, when the same “neutral” close-up of actor Ivan Mozhukhin was juxtaposed with, in turn, a bowl of soup, a dead woman lying in a coffin, and a little girl playing, leading audiences to assign a different emotion to Mozhukhin’s “performance” in each case. Before Rappaport restages this experiment a couple of times, with Seberg and Eastwood replacing Mozhukhin (taking his shots of the dead woman and the little girl from Carl Dreyer’s Ordet and Fritz Lang’s M, respectively), he informs us that Mozhukhin, after emigrating from Russia to France, was the father of the illegitimate Romain Gary, which leads to yet another string of speculative digressions.

A resourceful film critic as well as an acute social historian, Rappaport is alert to the less-than-obvious continuities between Jane Fonda in Barbarella and in her own workout tape many years later, and he’s no less adroit in summarizing the two basic kinds of American plays that were popular in the 50s — sex melodramas about “sexual repression and hysteria among the proles” and frothy sex comedies, usually set among the successful and the well-to-do. (In her Marshalltown, Iowa, high school before she was discovered by Preminger, Seberg starred in at least one outstanding example of each type — Picnic and Sabrina.) Comparing the varying degrees of protection enjoyed by Fonda, Redgrave, and Seberg when they became radical activists–because of their family backgrounds and their reputations — Rappaport is no less attentive to the overall shapes and developments of their respective careers. (Fonda, he is alarmed to note, eventually apologized for her antiwar protests — though she’s apparently never bothered to apologize for playing a bimbo in Barbarella.)

What fascinates Rappaport about Seberg’s bumpy career are those aspects that sexual ideology prevented us from seeing with any clarity in the 60s and early 70s, before feminism became a household term and a working discourse. “You can’t object to something unless there is a vocabulary that can describe the situation you’re in,” Hurt notes at one point. Despite this fact, after Godard cast Seberg in his first feature, Breathless — as the American girlfriend of the crook played by Jean-Paul Belmondo who ultimately betrays Belmondo to the police, which leads directly to his death — she refused to follow Godard’s instructions and filch the crook’s wallet while he lay dying. (As Rappaport points out, spectators at the time typically regarded her character as a nihilist and a bitch — check out Pauline Kael’s original review — while the cop-killing hero was considered a charmer.) Similarly, Seberg’s sphinxlike attributes in subsequent roles tended to make her a veritable symbol for “mysterious” femininity. She was an object of fearful speculation who was mythologized more often than humanized, probed, or understood.

Indeed, the feminist revisionism that lies at the heart of From the Journals of Jean Seberg is ultimately a consideration of the audience rather than an actor — a consideration of what the audience was prepared and unprepared to see between the mid-50s and the mid-70s. Much as Rock Hudson’s Home Movies uses the gay subtexts of Rock Hudson’s Hollywood movies as a route into a discussion of various denials of mainstream America over roughly the same period, this multifaceted follow-up, exploring the fear of the feminine in European as well as Hollywood movies, proposes another tragic, iconic mirror for our collective sexual panic. The fact that Hudson hid his sexuality from the public was an easy enough premise to build a movie around. The fact that Seberg’s own sexuality was employed to hide other things — in herself as well as in others — is a much more daunting proposition, leading in several directions at once. What those other things are is a subject this movie opens up but refuses to close down. For all his dogmatic opinions, Rappaport lays a lot of provocative evidence on the table, and we can’t help but make our own contributions to the subject.