From the May 1981 American Film. This is the third and last of my Resnais interview pieces from this period to be posted on this site . — J.R.

“You know, for all European kids of my age, America was a kind of fairyland,” recalled fifty-eight-year-old Alain Resnais on a recent trip to the United States. “We were born with the idea that there was another kind of country where everything was easy and perfect, like cartoon films, and there was a lot of money and freedom. I remember that when I was ten and I was looking at the French flag, I didn’t feel a thing. But when I was looking at the American flag, my heart was really beating.”

The French director also remembered that in his youth every French child had a distant relative who had gone off to America and was never heard from again. (In his own case, this was a great-grandfather who had disappeared into the wilds of Virginia.) The typical fantasy would be that the missing relative had made a fortune and would one day return to solve every problem. It’s the concept alluded to by the title of — and briefly mentioned by all three leading characters in — Mon Oncle d’Amérique, Resnais’ eighth and most recent feature, and his first major commercial success. The film got an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay.

Whether the new film can be said to be performing the role of American uncle to Resnais — whose previous graceful, offbeat movies (including Hiroshima mon amour, Last Year at Marienbad, Muriel, and Providence) have often provoked more comment than profit — it’s clear that America no longer seems as remote to him as it once did. “I think now it’s different. Because with TVs, with photos, with planes, with Concorde, it’s a fact that America is closer to Europe, which makes it less picturesque, less exotic in a way.”

What interests him most about American movies? “What I appreciate in American films is that they’re ab;e to do them. Directors seem to have enough money to make them visual enough. In Europe that’s a big problem for us, because we don’t have enough money to make films. So we’re always frustrated with the visual aspect of things; we always have to find a way to make it more economical. When I see some American films, I have the feeling that the director had the means that he wished to convey some visual impact.”

It’s easy to see why Resnais longs for bigger budgets. Two cherished current projects are a sword-and-sorcery fantasy (to be written by Jean Gruault, screenwriter of such classics as Jules and Jim and The Rise of Louis XIV, as well as Mon Oncle d’Amérique), and a thriller called The Inmates (to be written by comic book artist Stan Lee, the creator of Spiderman). The latter project was started more than a decade ago, during one of Resnais’ extended sojourns in the United States. Another sojourn was partially devoted to researching a still-unrealized documentary about the fantasy writer H.P. Lovecraft — whose hometown and sense of horror both left their indelible marks on Providence, a subsequent fiction feature written in English by playwright David Mercer.

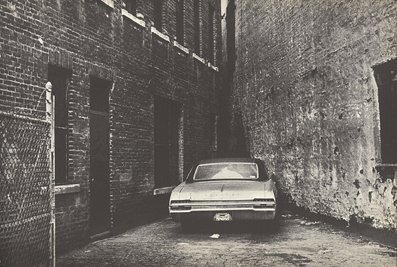

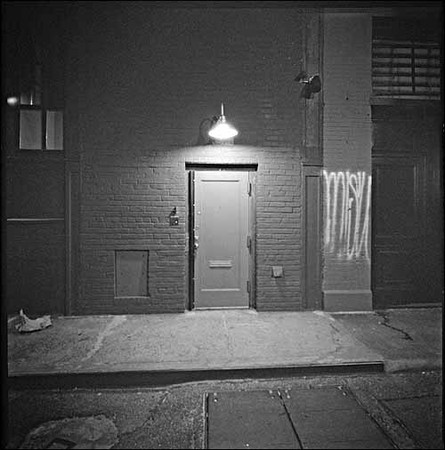

In a book of photographs by Resnais that has been published in France — mostly pictures of potential locations for unrealized films, many taken in New York during extensive walks over the past twenty years — there are some haunting glimpses of Staten Island associated with the Stan Lee project. They bring to mind the mysterious images of the South Bronx at the end of Mon Oncle d’Amérique.

***

Resnais was almost thirty-seven when he completed in the late fifties his first feature, Hiroshima mon amour, from a script by the celebrated New Novelist Marguerite Duras (now a prolific filmmaker herself). This has led some people to regard him as a late starter in the ranks of New Wave directors — at least alongside such colleagues as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard — when, in fact, the opposite is closer to the truth.

Resnais had already enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a director of short documentaries — most notably about painters (Van Gogh, Gaughin, and Picasso), African sculpture (Statues Also Die), the German death camps of World War II (Night and Fog), the Bibliothèque Nationale (Toute la mémoire du monde), and the making of plastics (Le chant du styrène) — before he ever started making features. (His first professional short, Van Gogh, won an Academy Award in 1949.) Even before that — in fact, from his preteens — he had made quite a few amateur films, in 8mm and 16mm.

More than one commentator has noted a disquieting similarity between Resnais’ successive treatments of a concentration camp and France’s largest library. Ecah orderly structure is traversed calmly by obsessively measured camera movements that seem to glide like surveillance guards past prisonlike enclosures.

This relationship is more a matter of elegant visual style than of narration. In his features, Resnais always assigns the task of writing the scripts to someone else — most often, a literary writer with whom he collaborates very closely. It is a method somewhat resembling that of Alfred Hitchcock — another careful planner and shy, formal craftsman with the imagination of a lonely child.

Where Resnais’ method differs most noticeably from Hitchcock’s is in the amount of creative space that he allows his scriptwriters — makinfg his films collaborations in the fullest sense of the word. The trick is to stage the right meeting of minds. In Resnais’ gound-breaking second feature, Last Year at Marienbad, this was initially a matter of agreeing upon certain abstract and formal principles with novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet, who was then instructed to flesh out specifics of story, action, and character. Resnais then performed a careful, creative edit on Robbe-Grillet’s script before beginning to shoot.

Another long-standing misapprehension about Resnais’ career — the notion that his approach and interests tend to be esoteric and intellectual — relates especially to Marienbad and the widespread bafflement and irritation it caused when it first appeared. A veritable Chinese box of narrative contradictions and chic, ponderous surfaces — set in a baroque luxury hotel in the middle of nowhere, and featuring three characters identified in the script only as A, M, and X — it was also a deadpan, ironic parody of diverse Hollywood intrigues and seductions (as were portions of Providence, including Miklós Rózsa’s lush score). That was a fact that tended to get overlooked in most of the lively debates that the movie inspired. While the chameleonlike temperament of Resnais and his lyrical style made him marvelously adaptable to Robbe-Grillet’s analytical viewpoint, neither was in any sense equivalent to it, as Robbe-Grillet’s own subsequent (and relatively flat-footed) films have demonstrated.

And for viewers who have had the opportunity to to see other Resnais features — including a drama about the wartime past set in Contemporary Bologne (Muriel), a warm and sentimental ode to underground anti-Franco leftists in French exile, with Yves Montand and Ingrid Thulin (La Guerre est finie), a foray into surrealist fantasy involving time travel (Je t’aime, Je t’aime), and a bittersweet, opulent period film with Jean-Paul Belmondo as a famous French financial swindler of the thirties (Stavisky…) — the common denominator of these films us scarcely heavy cogitation. Some critics have spoken of memory and nostalgia as the key factors. The impulse toward experimentation — evident in, say, Muriel and Je t’aime, Je t’aime — is usually more a matter of play than of punishing the audience.

***

Interestingly enough, the suspicion that Resnais is an intellectual is reactivated by the first fifteen minutes of Mon Oncle d’Amérique, which promises to be an experience of brain-taxing complexity. It’s a promise that, cheerfully and lucidly, is never kept. By the time the movie is fully under way, the careful construction guarantees that a supposedly indigestible stew of a lecture on the brain and tghree apparently unconnected stories come together as simply and clearly as a snifter of cognac. “Actually, while making a film,” Resnais recently told an interviewer, “the only thing I ask myself, each step of the way, with every single shot, is: Can this be understood?”

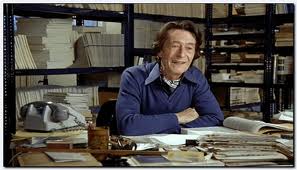

A further source of confusion about Resnais’ Gallic irony is that he tends to be much more modest than most of his scriptwriters — not to mention some of his interviewers. When I recently had the temerity to suggest that the theories of biologist and lecturer Henri Labori [see first photo below]t in Mon Oncle d’Amérique contradicted those of the French intellectual and Freudian disciple Jacques Lacan [see second photo below], Resnais was quick to confess, “I know thing about philosophy, science, biology, or anything like that,” and added, “I am totally unable to answer you, because I don’t know anything about Lacan, except that I’ve seen him at a party.” Then Resnais broke into laughter.

One suspects, though, that there are certain elements of a rather critical self-portrait present in the quasi-intellectual character Jean Le Gall (Roger-Pierre) in Mon Oncle d’Amérique, a news director for French radio and a distinguished author. Le Gall’s conversation with a colleague about the French minister of information brings to mind that the late André Malraux, minister of culture. was Resnais’ father-in-law. (His wife, Florence Malraux, works as an assistant director.)

But perhaps the real giveaway is the character’s Breton background, along with a sequence that shows him as a boy in a tree reading the illustrated adventures of the Gold King, an American hero (“Samuel Knight, orphan and millionaire”). It recalls Resnais’ own childhood (and adult) enthusiasm for comics and Anglo-American pop heroes. At a recent question-and-answer session with American graduate students in film and drama, Resnais remarked offhandedly that the tiny island off the Brittany coast where Jean Le Gall spends much of his youth is actually an island that Resnais himself knew well as a boy, and where he shot an 8mm film when he was twelve.

As Le Gall’s name suggests, the character is French to the core. And a paradoxical aspect of Resnais’ fascination with things American is that it’s one of the most French things about him. He even reports that after making an “Anglo-Saxon film,” Providence, he went to a lot of trouble to make Mon Oncle d’Amérique as French as possible. Could this, along with his light comic touch, help to account for the movie’s unusual success? “America doesn’t exist,” a French coporation executive in the film remarks at one point in a French cocktail lounge. “I know, I lived there.” The funny thing about such a gag is that, like Alain Resnais’ American uncle, it could only come from a Gallic sensibility.