This column for the 100th issue of Caimán cuadernos de cineis (Enero 2021) is basically an excerpt from and preview of a much longer essay about Kira Muratova written for the English feminist journal Another Gaze, and scheduled to run in its next issue early this year. Note: Arsenii Kniazkov has pointed out to me that Muratova is Ukrainian, so calling her Russian is a bit like calling Ousmane Sembene French.– J.R.

What is most provocative and sometimes pleasurable in both art and life can also sometimes be most maddening and aggravating. Kira Muratova’s films provide a good illustration of this principle because they have a disconcerting way of flirting with us and then slamming a door in our faces, sometimes even simultaneously. I’d like to suggest here that there’s a meaning and message behind her seeming madness — that a double-edged attitude of love/hatred towards both repetition and various institutions that promote an overall sense of continuity, security, and coherence, including family and the state, lies at the heart of her cinema, accounting for much of its bipolar energy.

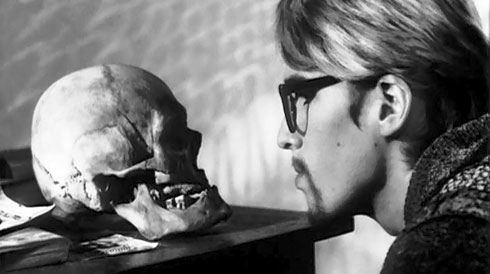

In her Chekhov’s Motives (2002, also known as Chekhovian Motifs), perhaps the strangest and most aggressively eccentric of all her black and white features, her incantatory uses of repetition are especially evident. This is how I described the film in the Chicago Reader:: “Members of a farming family incessantly repeat the same lines of dialogue while a student prepares to leave home for school; guests at an interminable wedding cackle maniacally while the ghost of the groom’s lover interferes with the ceremony. Born in 1934, the great Russian filmmaker Kira Muratova (The Asthenic Syndrome) seems to get wilder and more transgressive with every passing year. This updated merging of two early Anton Chekhov texts (the short play Tatiana Repina and the story ‘Difficult People’) veers closer to the mad lucidity of Gogol than to the wry realism of The Cherry Orchard. I found the extreme stylization mesmerizing, hilarious, and ultimately closer to hyperrealism than to absurdism, though if you enter this without any warning you might wind up fleeing in terror.”

In interviews, Muratova maintained that the reason why she made Chekhov’s Motives was to support love and family values — and, unlikely as this sounds, there is reason to believe that she was being sincere. Because the fictional worlds of Chekhov are full of commonplace statements, Muratova’s insistence on turning them into manic mantras (that is, mantras that are anything but meditative, and delivered passionately rather than mechanically) seems at least partially a function of considering how strange they might sound or become —and how they might reduce, elevate, or at least level out a family meal by being treated as a strident form of music, a roundelay of refrains — a relation that is even acknowledged in this film’s title. (We even see an infant nodding rhythmically and sleepily to one of the father’s tirades, as if being ‘conducted’ by it.) Within this framework, rejecting or embracing one’s family or one’s state may ultimately (and tragicomically) prove to be two alternate versions of the same maniacal process.