Written for the Viennale in August 2020 for a late October publication called Textur #2 and devoted to Kelly Reichardt. — J.R.

“More nameless things around here than you can shake an eel at.”

— King-Lu in First Cow

I suspect that the first important step in learning how to process Kelly Reichardt’s films is discovering how not to watch them. A few unfortunate viewing habits have already clustered around her seven features to date, fed by buzz-words ranging from “neorealism” (applied ahistorically) to “slow cinema” (an ahistorical term to begin with) — especially inappropriate with a filmmaker so acutely attuned to history, including a capacity to view the present historically — and, in keeping with much auteurist criticism, confusing the personal with the autobiographical.

Interviewed by Katherine Fusco and Nicole Seymour, the coauthors of a monograph about her, Reichardt rightly resists fully accepting any of these categories,[1] however useful they might appear as journalistic shortcuts. (E.g., J. Hoberman on Wendy and Lucy in the Village Voice: “Reichardt has choreographed one of the most stripped-down existential quests since Vittorio De Sica sent his unemployed worker wandering through the streets of Rome searching for his purloined bicycle, and as heartbreaking a dog story as De Sica’s Umberto D.”)[2]

Admittedly, her atypical first feature, River of Grass (1994), might foster some false impressions by having been shot in Florida, where Reichardt grew up, and by making its heroine’s father, like her own, a crime scene detective. But if this film’s title anticipates her subsequent oeuvre by focusing on a wild landscape, most of its images tell a different story – a wry comedy of absence played in counterpoint to the second-hand media images imbibed by the inept protagonists, doggedly viewing themselves as a generic “couple on the run” when they can’t even begin to match that movie cliché. When, at the film’s end, Cozy Ryder (Lisa Bowman), a bored ex-housewife and negligent mother, actually shoots her would-be partner in crime (Larry Fessenden) — the film’s only real violence, occurring offscreen, without her even looking at him — her main motivation seems to be more boredom, along with rage at having been conned into regarding the two of them as some version of Bonnie and Clyde.

Furthermore, the film’s punchy style, with its Godardian chapter headings and its editing synched to offscreen jazz drumming by the heroine’s father, seems to introduce Reichardt as a montage-oriented filmmaker — another false clue, like the film’s title, because it was Fessenden, not Reichardt, who edited the footage. One suspects that if Reichardt shared anything at all with her hapless heroine, it was a burning desire to escape from Florida.

Once she left, understandings of what came next vary. Most accounts, defining her career in relation to commerce and theatrical features, posit a twelve-year gap in her work between River of Grass (1994) and Old Joy (2006) that is made to seem almost Biblical: twelve years spent in the wilderness. And for about five of those years, she was crashing on various friends’ sofas in New York, giving her a certain kinship with Kurt (Will Oldham), the troubled drifter in Old Joy (another rare autobiographical element in her work she has admitted to — “Stuff sneaks in,” she told Fusco and Seymour — to which one might add the itinerant Wendy in Wendy and Lucy, a film co-starring her own dog). But insofar as all her features are largely set in some kind of wilderness, physical and/or spiritual, most often in the Pacific Northwest and usually among off-the-chart characters, a closer look at what’s being defined as a gap and as wilderness becomes essential.

Three items in Reichardt’s filmography, commonly omitted —Ode (1999, 46 minutes), a super-8 mm narrative made mostly with a two-person cast and a two-person crew (including Reichardt as cinematographer), adapted by Reichardt from a novel by Herman Raucher, and two non-narrative shorts, Then a Year (2001, 14 minutes) and Travis (2004, 12 minutes) — fill this gap, as does the beginning of Reichardt’s teaching career; she would later join the faculty at Bard College, in a film department oriented towards experimental non-narrative work. (First Cow is dedicated to the memory of one of her cherished colleagues there, the late Peter Hutton.) It’s worth adding that Ode is the last Reichardt film not to be edited by her and that she began as a solo editor on her two shorts. She has expressed some ambivalence about these three films -– none has turned up as an extra on any of the DVDs or Blu-Rays of her features -– without in any way rejecting their status as independent or experimental efforts. “It’s alright; it’s good they are lost,” she assured interviewer Orla Smith in a Canadian anthology devoted to her work, suggestively called Roads to Nowhere.[3] “They were just learning tools.”

Yet if we also use them as learning tools in relation to Reichardt’s subsequent work, they offer many intriguing lessons. All three films place an emphasis on music and/or using words musically as a formal device that is also present in River of Grass but relatively attenuated in Reichardt’s subsequent work, apart from the importance of the sound editing. Ode is based on the pop song “Ode to Billy Joe,” about a rural teenage suicide, and the radical and minimalist Travis uses “guitar noises” and a few `looped words spoken by a bereaved mother about her son killed in Afghanistan, taken from a Portland radio broadcast and endlessly repeated, accompanied by unidentifiable out-of-focus images of various colors. The exclusion of the source and meaning of the woman’s voice, obliquely referenced only in the film’s title, makes this a purely formalist work in contrast to Then a Year, whose verbal fragments and suburban landscapes point towards both a love story and a crime scene — the two unfulfilled fantasies hovering over River of Grass.

One could argue, in fact, that unfulfilled fantasies belonging to viewers and characters alike are present in all of Reichardt’s features — namely, the failure of life and the world (nature, humans, society, even sometimes animals) to conform to the expectations molded by culture, genres, and many other conditioned reflexes. It’s a condition akin to artistic frustration, but one applied to life more than art. (Birds play an important role in Reinhardt’s universe, and a rare moment of clear communication in Certain Women ironically comments on how more adept quails usually are in communicating with one another.)

More generally, the significance of Ode, Then a Year, and Travis on Kelly Reichardt’s career is that they represent early efforts to reinvent herself — and they’re by no means the last. Indeed, these films are so dissimilar from her features that they seem like the work of different filmmakers. (If Ode – despite being shot in super-8, which Reichardt has described as a liberating experience – seems aimed at a mainstream audience, this can hardly be said of either Then a Year or Travis. Moreover, in her writing and interviews, Reichardt’s cinematic reference points are all over the map, encompassing Shampoo (1975) and (in her written appreciation of critic Manny Farber) Robert Altman as well as Anthony Mann, Kenji Mizoguchi, Satyajit Ray, and her experimental colleagues at Bard. Her relocation to Oregon and collaborations with writer Jonathan Raymond and (on her last four features) cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt count as other such reinventions, as does her move to Montana (and her decision to take a break from collaborating with Raymond to work from short stories by Maile Meloy) on Certain Women.

Reading the two short stories adapted by Reichardt — “Old Joy” and “Train Choir”, the first and last stories in Raymond’s collection Livability[4] – into Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy, I find the films’ overall faithfulness (especially to the dialogue, apart from trimming) and departures from the originals equally striking. “Old Joy” is recounted is in the first person by Mark, which allows for many more back stories, but doesn’t allow for the film’s epilogue showing Kurt alone on the street, after Mark drops him off. Most conspicuously missing are the film’s two females, Mark’s pregnant wife and his dog Lucy. (The terse and somewhat testy dialogue between Mark and his wife when he asks for her permission — or, as she says, pretends to ask her permission — to drive to the hot springs with Kurt already hints that their marriage is less than ideal.) It’s worth adding that Kurt does the driving in the story and Mark supplies the marijuana (more of which is smoked) — and that Mark as a focused homebody and Kurt as a restless wanderer are to some extent first drafts of the more loving and interactive duo of “Cookie” and King-Lu in First Cow.

The dogs in both “Train Choir” and Wendy and Lucy have the same name, Lucy, raising the strong possibility that Reichardt named her own dog — belonging to a different kind of mixed breed — after the dog in the story. (Certain Women, one should add, is dedicated to Lucy.) Raymond’s narrative is in the third person but from the viewpoint of his heroine, Verna, which again allows for more back stories — about Verna’s overall car journey from Indiana as well as her expectations about her arrival in Alaska. The significance of trains in the original story isn’t abandoned, even though the title is: Reichardt’s opening shot is of a train yard, and she uses passing trains throughout as poetic punctuations to evoke distance, danger, fear (the threat of senseless male violence, which also crops up in the first story of Certain Women and throughout First Cow) or other kinds of uncertainty, as well as a certain calming continuity in spite of everything else.

***

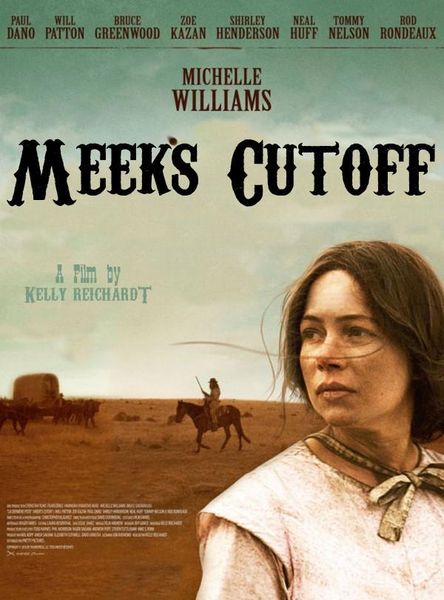

Apart from their shared counter-cultural politics, one trait Reichardt seems to share with minimalist independent Jim Jarmusch, whose Dead Man (1995) suggests some parallels with Meek’s Cutoff and First Cow — and whose Coffee and Cigarettes (2003) has some looser parallels with Certain Women — is that her minimalism sometimes serves as a practical consideration and is not only a matter of aesthetics. One instance of this is the decision in Meek’s Cutoff to have Joseph Meek’s lost wagon train in 1845 consist of eight people and three wagons rather than the estimated 1500 people on that epic trek cited by historians. And Reichardt has often pointed out that her artistic control, including final cut, is virtually guaranteed by her films’ modest budgets.

Other minimalist strategies in Meek’s Cutoff include filming at night and in long shot and using dialogue sparsely, all of which Reichardt does in her other features. The avoidance of a widescreen aspect ratio can be justified both by the film’s privileging of the viewpoints of the women, framed by their spacious bonnets, and by the present-tense aspects of the journey that makes many events unforeseeable. The decision not to subtitle the Indian character’s dialogue is predicated on Reinhardt’s desire for viewers to share the ignorance of her other characters, whereas Jarmusch’s expressed motivation for his own refusal to subtitle the Native American dialogue was to offer a special ‘gift’ to the film’s Native American viewers — not an option available to Reichardt, because the Cayuse language spoken in her film is nearly extinct.

Reinhardt’s minimalist procedures are already well established in Old Joy, which also recruits at least two of her major future collaborators, writer Jonathan Raymond (who will write or cowrite all but one of her subsequent features to date) and her dog Lucy (the eponymous costar of her next feature, Wendy and Lucy), along with Michelle Williams, another major collaborator who, like Lucy, will wind up appearing in three Reichardt features, albeit playing a very different character each time.

It seems important to credit Lucy’s collaboration, not only because Reichardt also used to bring her along to her Bard classes (as is indicated in Old Joy, her dog doesn’t like to be excluded from human activities) but also because, like many other animals featured in Reichardt’s work, she contributes a documentary dimension by virtue of being not entirely predictable or controllable, which affects all the crew members and actors in turn — keeping all of them on their toes and even keeping them honest, so to speak.

The economy that Wendy and Lucy is concerned with is not only a matter of dwindling money, time, and resources (“You can’t get a job without a job, you can’t get an address without an address,” says a kindly security guard); it’s also a question of narrative economy considering how little we know about Wendy apart from her immediate concerns (car, dog, money). And immediate concerns within short time frames are basic to all Reichardt features.

I’m puzzled why Reichardt’s next feature, Night Moves (2013), borrows its title from one of Arthur Penn’s better features, a 1975 political thriller that also features a boat called Night Moves. Even though it’s impeccably realized (shot, acted, directed), this is my least favorite Reinhardt feature, largely because it’s the most conventional and predictable—even more so in some respects than Ode. Rightly or wrongly, I tend to see this film about not very bright eco-terrorists — a cooperative farm worker (Jesse Eisenberg), a rich employee at a spa (Dakota Fanning), and a former Marine (Peter Sarsgaard) blowing up a hydroelectric dam in Oregon — as an effort to do something commercial with popular young stars (Eisenberg and Fanning) going through all-too-familiar genre exercises. To her credit, Reichardt doesn’t compromise her meditative style while doing this, and she even includes a thoughtful dialogue scene explaining why the plot to bomb the dam was misguided. But even if her plot is “character driven,” as she has said, the characters who drive the narrative don’t strike me as being very interesting or substantial. I hasten to add that If I ever find any critical defenses of Night Moves that don’t bore me as well, I’d be more than happy to change my mind.

The changes made by Reichardt to Meloy’s “Native Sandstone” for the second story in Certain Women are mostly related to gender — though less so than the re-gendering applied to “Travis, B.,” the first story in Meloy’s second collection, Both Ways is the Only Way I Want It,[5] which turns its central character, a ranch hand, from male to female. (The original hero is alluded to only briefly in the film, as the ranch hand’s brother.) The sandstone story is restricted to the visit of a couple, Susan and Clay, to Albert, an elderly local who has a pile of sandstone blocks in his front yard, the remains of an ancient demolished schoolhouse, that Susan wants for the summer house that Clay is planning to build. The story, told in the third person, is anchored in Susan’s reactions, largely self-critical. In the film — whose action begins earlier, with the wife jogging alone — the couple, renamed Gina (Michelle Williams) and Ryan (James Le Gros), have a sullen teenage daughter named Guthrie (Sara Rodier), who resents both her mother and being along on the trip, choosing to remain in the car with her earphones while her parents visit Albert (René Auberjonois). After Albert tentatively agrees to part with his sandstone blocks and Gina goes out to look at them, Albert remarks to Ryan, “Your wife works for you,” to which Ryan replies, “That’s funny. No — she’s the boss, actually.” This exchange isn’t in the story, and the wife’s bossy character registers differently here because we aren’t privy to so many self-doubts, making her chiding of her husband and daughter seem more self-centered.

This is my subjective reaction, and it’s a delicate matter because all three of Meloy’s stories and Reichardt’s film are concerned with the ethics of everyday human interactions, according to which the wife’s behavior even in Meloy’s story seems less principled than the behavior of a patient lawyer (Laura Dern) handling an emotionally unstable former client (Jared Harris) in “Tome” and the film’s opening story. The closest thing to an epiphany in “Native Sandstone” is the wife’s sad admission in the final paragraph that she doesn’t even know what to do with those blocks once she has them. Yet the fact that Albert mostly ignores her and Ryan fails to ask him about the sandstone, as she requested, adds more ambiguous layers to the scene. Other subjective responses are indeed possible, and a vital part of Reichardt’s storytelling strategies are to make them possible — even when they risk producing boredom, as they do for me in Night Moves. In the prologue added to the sandstone story, Gina’s seeming rapport with nature and the film’s focus on landscape might lead some viewers to arrive at more sympathetic feelings about the character, and in the added epilogue, Gina busily cooking for friends and family, then sneaking a cigarette while gazing at the pile of blocks, might do that as well.

Story collections that are structured with interactive parts are rare: James Joyce’s Dubliners is one example, and Meloy herself has suggested that J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories is another. Reinhardt’s own collection, composed of three Meloy stories, innovates with this form by following her third story with epilogues to all three (which in the first story is Meloy’s own conclusion). The thematic constants throughout include obsessional behavior, social awkwardness, and loneliness. There are lawyers in the first and third stories (with Lily Gladstone’s shy stable hand becoming helplessly smitten with Kristen Stewart’s lawyer teacher) and building/construction figures in the first and second (carpentry is the former job of Laura Dern’s aggrieved client, causing his disability). Making them all contribute to telling the same story is Reichardt’s special talent, and even more special is her refusal to give her characters tribal identities. The ranch hand in “Travis, B.” — a title referring to the lawyer-teacher, Beth Travis, not to him — is named Chet Moran and he has a mother who’s “three-quarters Cheyenne” and an Irish father. His female replacement in the film is nameless and we’re told nothing about her ethnic background (although Lily Gladstone, who plays her, is Native American) or her sexual orientation, obliging us to understand her without such cliché-ridden standbys as “indigenous” or “lesbian”, which, like “neorealism” and “slow cinema,” often confuse as much as they clarify.

The same approach couldn’t work for First Cow (2019), mostly set in 1820s Oregon, an almost prehistorical period where tribal definitions gain even greater primacy than in Meek’s Cutoff. The film unfolds in a multiracial, multiethnic wilderness full of both immigrants and “Indians” and dominated by the beaver trade — a world whose creation is perhaps the film’s most impressive accomplishment, along with its voluptuous capturing of nature. “You speak good English — for an Indian,” says Otis “Cookie” Figowitz (John Magaro), one of the two protagonists, who cooks for fur trappers, just after meeting the other in the wilderness, who is on the run from a band of Russians after killing a man. “Uh, I’m not Indian. I’m Chinese,” replies King-Lu (Orion Lee). At the same time, the film begins with one of William Blake’s Proverbs of Hell — “The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship” — before showing us a woman and her dog discovering two skeletons buried side by side in the woods. The forging of human kinship in a savage wilderness where the multicultural injustices and inequalities of the present day are already clearly in evidence is the film’s implicit theme, at once simple and complex, with its specters of early capitalism in a settlement that hasn’t yet been defined as Oregon. (One might add that smaller examples of succeeding or failing in human interactions — what Reichardt describes as an interest in “small politics” — are also the focus of Certain Women.)

I haven’t read Raymond’s first novel, The Half-Life,[6] which he and Reinhardt adapted for the screenplay. I’m told it spans four decades but is also partly set in Portland in the 1990s, includes a trip to China, and King-Lu combines two of its characters. Yet its plot doesn’t include a cow, so apparently its compression is comparable to that done by Meek’s Cutoff in relation to the historical record. It seems to reflect as well as anticipate the present in an uncanny number of ways, introducing us to a strange world of primitive unrest seeking order both peacefully and violently, via sharing or grabbing. As Reichardt’s wilderness steadily grows wider, richer, and more mysterious, it also becomes more recognizable as we cross its unpredictable contours.

End Notes

[1] Katherine Fusco and Nicole Seymour, Kelly Reichardt (Urbana/Chicago/ Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2017).

[2] J. Hoberman, “Wendy and Lucy,” in Village Voice (New York), 10.12.08, available online at https://www.villagevoice.com/2008/12/10/wendy-and-lucy/.

[3] Orla Smith, “An Interview with Kelly Reichardt,” in Alex Heeney and Orla Smith, eds., Roads to Nowhere (Toronto: Seventh Row, 2020), pp. 16-25, p. .

[4] Jonathan Raymond, Livability (New York/London/Berlin: Bloomsbury, 2009).

[5] Maile Meloy, Both Ways is the Only Way I Want It (New York: Riverhead Books, 2009).

[6] Jonathan Raymond, The Half Life (New York: Bloomsbury, 2004).