From the Chicago Reader (August 10, 2001). — J.R.

Under the Sand

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Francois Ozon

Written by Ozon, Emmanuele Bernheim, Marina de Van, and Marcia Romano

With Charlotte Rampling, Bruno Cremer, Jacques Nolot, and Alexandra Stewart.

Ghost World

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Terry Zwigoff

Written by Daniel Clowes and Zwigoff

With Thora Birch, Steve Buscemi, Scarlett Johansson, Brad Renfro, Illeana Douglas, Bob Balaban, and Stacey Travis.

The Deep End

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Scott McGehee and David Siegel

With Tilda Swinton, Goran Visnjic, Jonathan Tucker, Peter Donat, Josh Lucas, and Raymond Barry.

It’s often said that strong roles for women are rare nowadays, but three new movies — Under the Sand, Ghost World, and The Deep End — have the virtue of handing a juicy, sympathetic part to a talented actress and letting her run with it. All three are directed by men, which raises the question of whether women will find these portraits as potent and sensitive as I do. Yet even if they qualify to some degree as male fantasies, I’d argue that they’re more in touch with our everyday reality and our history than a male fantasy like Apocalypse Now Redux.

The ages of the directors of Under the Sand and Ghost World and of their lead characters are also an issue. Francois Ozon, who’s in his mid-30s, focuses on a woman in her 50s (Charlotte Rampling); Terry Zwigoff, who’s middle-aged, focuses on a teenager who’s about to finish high school (Thora Birch). I’m astonished by the perceptiveness of both directors, but I’m middle-aged myself and that obviously inflects my opinion: I’m grateful that Ozon takes the trouble to empathize with a woman who’s 20 years older than himself, and I might be partial to Zwigoff’s view of adolescence because we’re from the same generation. (Daniel Clowes, Zwigoff’s cowriter, is 40.)

I assume that Scott McGehee and David Siegel — the writers, directors, and producers of The Deep End — are relatively young and that they’re younger than their star, Tilda Swinton. They’re remaking a first-rate 40s melodrama — The Reckless Moment, directed by the great Max Ophüls and adapted from a 40s novel, Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall — which can be seen as another effort to reach across generations. McGehee and Siegel have updated the story to the present, dropped a black maid, substituted a gay teenage son for a straight teenage daughter, and shifted the suburban locale to Lake Tahoe, but shards of the story’s noirish origins remain. The plot concerns a middle-class housewife and mother who finds herself defending her son against blackmail — and keeping him less informed about her intricate mop-up activities than the mother in the original did — and then improbably, yet touchingly, developing a tender relationship with the blackmailer’s henchman.

As the henchman who falls in love with his victim, Goran Visnjic can’t hold a candle to James Mason in The Reckless Moment, but Swinton manages to make us forget her own glamorous predecessor, Joan Bennett, by conceiving the part so differently that comparisons aren’t meaningful. (That Swinton was born in Scotland and plays most often in English films surely helps.) In any case, it’s she who singlehandedly veers the film away from the academicism and postmodernism (both stemming from the noir aspects) of McGehee and Siegel’s previous feature, Suture, by giving her hausfrau heroine an almost obsessional sense of middle-class routine and propriety. Practically everyone else in the story shows traces of the noirish material, sliding into all-too-familiar types, but Swinton makes the misogynist undertones of noir irrelevant to her character. Far from being any sort of bitch goddess, she’s a powerhouse of controlled energy; essentially, she belongs in another movie, and it’s mainly this other movie that makes The Deep End worth seeing. For everything else, you’re better off tracking down the original — not an easy matter, alas, because, like so many other gems in Hollywood auteurist cinema, it isn’t on video.

Ozon, the only director here who started from an original story, asked three women to help him with his script. His story concerns Marie (Rampling), an English-born woman who teaches English literature in Paris. She and her French husband Jean (Bruno Cremer) go on vacation to their country house near the sea, and one day he goes off to take a swim and never comes back. The remainder of the film is devoted not to solving this mystery in any definitive way — though we may wind up concluding, along with Marie, that the disappearance was most likely suicide — but to chronicling Marie’s slow, incremental adjustment to her loss. She still imagines her husband is with her much of the time — something the film shows us from her viewpoint — and continues to speak of him in the present tense, even though her friends use the past. She picks up a lover named Vincent (Jacques Nolot) and enjoys his company — she’s particularly struck by the fact that he, unlike Jean, isn’t overweight, so sex is a lot less cumbersome — but this relationship appears to be abruptly cut off the moment he tries to get her to accept her loss.

Rampling, like Susan Sarandon, is far more interesting, accomplished, and attractive in middle age than she was in her 20s, and this film takes full advantage of this fact. One of the ways it does this is by displacing the issue of what happened to Jean and why — a displacement that feels very real, given all of the mysteries in life that remain unsolved — and instead concentrating on the psychological ramifications of the disappearance for Marie, which ultimately seem more interesting. This is a film of nuances, and Rampling inflects these nuances not as if she’s performing a score but as if she’s discovering certain things for the first time. (By comparison, her earlier performances often gave the impression that she thought she had nothing to learn — and they tended to fall flat.)

Ozon was asked in an interview what Emmanuele Bernheim, the first of the three women writers listed in the credits, had contributed to the story, and he said, “She came in at the end. I needed a woman’s point of view that would confirm the choices that I had made about Marie’s character. I wanted to know whether they were plausible, whether I was going the wrong way, particularly with regard to Marie’s sexuality. She had seen the first part of the film and the imposing figure of Cremer, and she helped me to work out this idea about the complementary figures of Jean and Vincent, to balance the gentleness of one against the imposing presence of the other.”

Nothing is said about Marina de Van or Marcia Romano, the two other screenwriters credited, but their presence also points toward Ozon’s willingness to expand his own range of understanding. I must confess that I was so turned off by the flippancy of one of his early short films, See the Sea (1997), that I avoided his first three features, Sitcom, Criminal Lovers, and Water Drops on Burning Rocks. (My conversion closely parallels that of Frederic Bonnaud, which he describes in the July-August issue of Film Comment — though he has seen all three of the features I missed and finds only the last of them defensible.) Whatever has happened to Ozon since then, I won’t avoid his next feature.

The source of Ghost World is a highly respected comic book by Daniel Clowes, for which I have no particular affinity. My main route into this movie is Zwigoff’s feature-length documentary about comic-book artist Robert Crumb, which is often recalled here. A major character in the film is Seymour, a reclusive collector of rare jazz and blues 78s who has no counterpart in the Clowes comic book but who bears many resemblances to both Crumb and Zwigoff. And Sophie Crumb, Robert’s teenage daughter, drew the cartoons we see in the sketchbook of Enid (Thora Birch), the teenage heroine.

Like its central character, the plot of Ghost World basically drifts rather than proceeds in any clear or purposeful direction, and despite some awkward allegorical and psychological touches near the end (relatively disconnected bits about a phantom bus stop and Seymour’s relation to his shrink and mother), the absence of conventional closure is part of what’s so brave about the movie — as brave in a way as Enid herself. Disdainful of almost everything she sees around her — even more so than her best friend and classmate, the slightly better adjusted Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) — she discovers that she has to take an art course in summer school if she’s to graduate from high school.

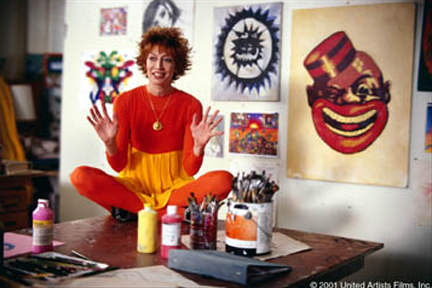

This occasions the movie’s most hilarious subplot — a nightmarishly believable satire of American art “appreciation” classes, this one presided over by a dopey former hippie named Roberta (Illeana Douglas doing a nice approximation of a corrosive Elaine May routine), which provides a plausible account of why so many Americans wind up hating art. (Part of this plays like a gloss on a sentence from Robert Hughes’s Culture of Complaint: “The self is now the sacred cow of American culture, self-esteem is sacrosanct, and so we labor to turn arts education into a system in which no one can fail.”) There’s an especially brilliant sequence in which the camera pans past student artworks while Roberta rattles on about their “meanings,” and it’s entirely to the credit of the script that Enid winds up seeming as clueless and as confused about these matters as her teacher; we, unlike Roberta, know that she’s a talented cartoonist, but her ability is made to seem extraneous to what passes for her education.

Enid avoids work except for when Rebecca talks her into a job she can’t hold on to — working the concessions stand at a movie multiplex, another one of this movie’s funnier bits — and she hopes to share an apartment with her friend by the end of summer. She also finds herself drawn to Seymour after finding him through a prank: he’d placed a classified ad hoping to meet again a woman he’d encountered by chance; she pretends to be that woman and calls to set up a rendezvous in a coffee shop, then turns up with Rebecca to watch him wait from afar. Not at all sure whether she’s really attracted to him, Enid befriends him after buying one of his records at a garage sale and promises to help him find a girlfriend. Then he hears from the woman he’d hoped to find through his ad and begins a tentative relationship with her, and Enid isn’t comfortable with this state of affairs. Awkward and alienated as only a teenager can be, she loathes her father (Bob Balaban) and stepmother (Teri Garr) as much as her future prospects; Birch makes the character an uncanny encapsulation of adolescent agonies without ever romanticizing or sentimentalizing her attitudes, and Clowes and Zwigoff never allow us to patronize her.

The movie basically chugs along through a series of minor events over the course of the summer — or major events, such as Enid sleeping with Seymour and getting him to drop his girlfriend, that she treats like minor events. Birch, who began acting as a toddler and was in some respects the most interesting actor in American Beauty, holds most of the movie together through the sheer force of her blocky personality, though Buscemi, in the best performance of his that I’ve seen, gives her a run for her money. What emerges is a pretty convincing portrait of what it means to be alive and trying to get by in America at the moment — a grim portrait that’s rendered with so much sweetness, warmth, and openness that it hurts.